Princeton Is ‘Quiet Ivy’ No More as Raucous Israel Debate Roils Campus

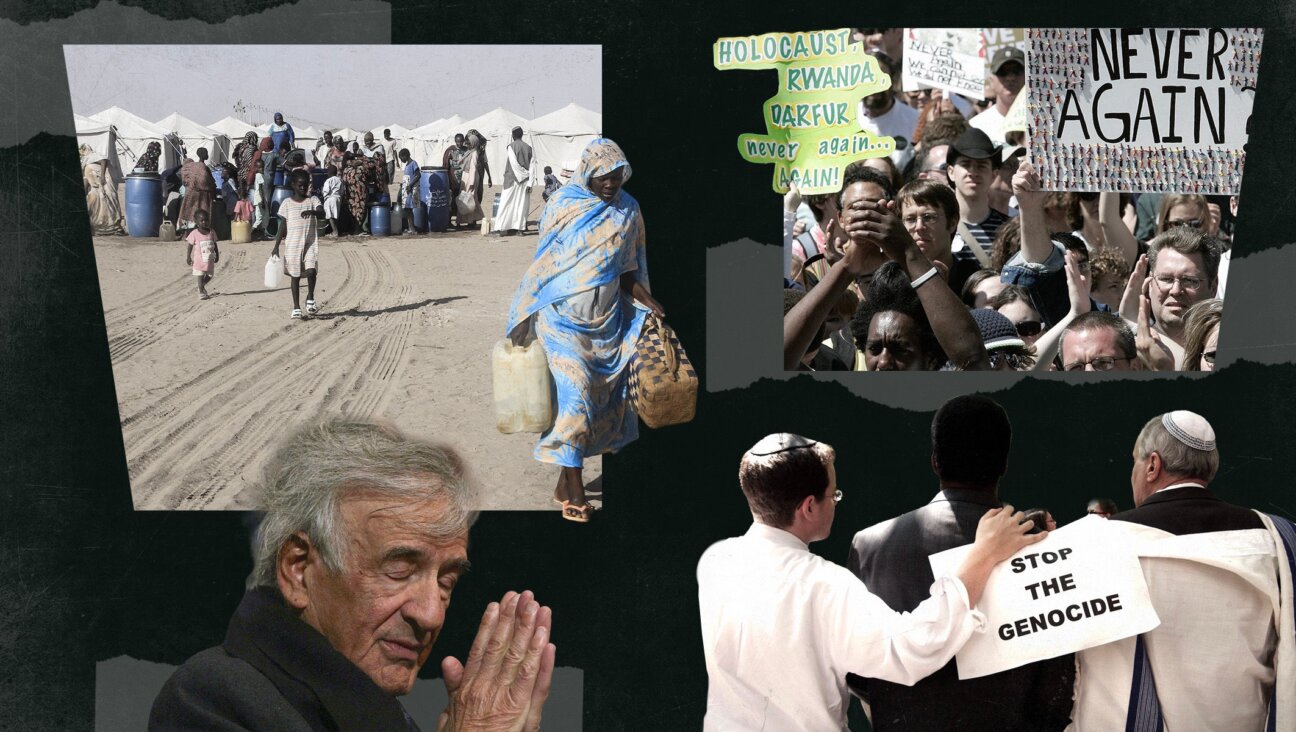

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Princeton University has long been known as the “conservative Ivy.” It’s a reference that encompasses not just the school’s centrist political image when compared with Ivy League universities like Harvard or Brown, but also its bucolic atmosphere and generally quiescent student body.

But Princeton’s cultivated image of ivory tower calm seemed to vanish like a daguerreotype from another era recently, when student activists succeeded in putting the question of divestment from Israel up for a vote before the entire student body. With breathtaking speed, students from both sides of the issue began accusing each other of tearing down campaign posters, misrepresenting information and making offensive social media posts. Charges of anti-Semitism, Islamophobia and hatred of Arabs also flew over social media.

Other campuses have experienced similar waves of tension when the issue of Israel and the Palestinians has come up. But those swept up in the fervor have generally been limited in number. At most schools, the decisions were debated and voted on by student governments. This drew in mostly those in campus politics and students who were sufficiently fervent or well informed to involve themselves. Princeton’s referendum marked one of the few times that an entire student body had the opportunity to vote. This put the issue in the hands of students who previously had little or no knowledge of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Suddenly, these students were posed with — or maybe, assailed with — the challenge of coming up with a judgment about it.

For Katie Horvath, a member of the Princeton Divests Coalition, this was part of the attraction of the studentwide vote approach. “We wanted this to be a consciousness-raising campaign,” she said. “We wanted this to be something that everyone had to engage with.”

It was the Princeton Divests Coalition that took advantage of a provision in the bylaws of Princeton’s student government that allows questions to be put to the whole student body in the form of a referendum. The coalition students had to gather 200 signatures on a petition to initiate the referendum, which was voted on alongside the spring student elections, from April 20 through April 22.

The proposal put to the students notably did not single out Israel alone for oppressing the Palestinians. It asked whether the school’s trustees should be called on to divest from “multinational corporations that maintain the infrastructure of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, facilitate Israel’s and Egypt’s collective punishment of Palestinian civilians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, or facilitate state repression against Palestinians by Israeli, Egyptian and Palestinian Authority security.”

The companies the referendum cited as divestment targets by name were American: Caterpillar, which provides bulldozers used to demolish Palestinian homes, a practice condemned by the U.S. State Department’s annual human rights report; Hewlett-Packard Co., which produces bio-scanners used at checkpoints on the Israeli-occupied West Bank to control Palestinian movement for what Israel says are security purposes, and Combined Systems Inc., which manufactures tear gas used against protesters.

The results, announced on April 24, gave a narrow victory to divestment opponents, who won over proponents by 52.5%–47.5%. Some 2,032 students, or almost 39% of all undergraduates at Princeton, participated in the balloting,

In the days leading up to and during the voting period, posters showed up around every light pole and on every bulletin board. Fliers covered the dining hall tables, and each day the organizations set up tables in Frist Campus Center, hoping to catch the attention of the hundreds of students who walked by.

But the campaign-related discourse sometimes flamed into hate speech, and even into threats.

Mohamed El-Dirany co-authored a pro-divestment column in the campus paper about Egypt because of his Egyptian background, and in response received threatening messages and emails.

“I forwarded your BS article about Egypt to authorities. If you ever set foot in Egypt, you’ll be arrested,” one email said.

El-Dirany, a freshman, volunteered to be the sponsor of the referendum, placing his name on the formal document and was thus, he said, perceived by some as “leading the referendum.”

Social media played a huge role in both sides’ campaigns, from promoting videos and photographs to advertising events and setting up discussions. One student posted a series of screenshots on his Facebook page from Yik Yak, the site that allows users to post anonymous comments, highlighting anti-Semitic and offensive Yaks under the heading “Criticizing Israel isn’t anti-Semitic. This is.” Yaks included “Jews have huge noses,” and a thread that began with “Jewish lives matter” but ended with “No they dont (sic).”

Joshua Leifer, a co-founder of the Alliance of Jewish Progressives, actually downloaded Yik Yak specifically to be aware of what was taking place on that social media platform. But Leifer deleted the app almost immediately because of the stress he experienced just reading the outrageous comments.

“I think Yik Yak on campus isn’t representative of the general campus opinion,” Leifer said.

Daniel Kurtzer, a Middle East studies professor who is a former U.S. ambassador to Israel and to Egypt and a vocal anti-divestment figure, said that the tensions on campus and online had grown inappropriate.

“Within certain bounds, there should be tolerance for different kinds of discourse,” he said. But he stressed, “I oppose fully the idea that people may be tearing down posters, or Yik Yak, where people can post anonymous things and feel freer to say things they shouldn’t say.”

History and Near Eastern studies professor Max Weiss, an author of the faculty petition for divestment that included 60 tenured faculty members’ signatures, took note of the way that social media actually discourages direct and open discourse.

“The fact that there is not open deliberation among people who disagree is actually a sign of a lack of healthy political discourse on campus,” he said. “I would encourage students to voice their opinions. If it is emotional and impassioned, so be it — but face to face as well as on social media.”

Two other schools have put divestment votes to their entire student bodies, though neither made much news at the time. In 2014, students at DePaul University, in Chicago, passed a divestment resolution by 54%–46%. At San Diego State, students rejected a comparable resolution in April by a vote of 53%–47%. The votes at these two schools, and now at Princeton, suggest that whatever the outcome in any particular case, this is now a very live and closely divided question for American college students.

Currently, divestment resolutions are being considered by student government bodies at the University of New Mexico; Bowdoin College, in Maine; Wisconsin’s Marquette University; Ohio State University, and the University of Texas at Austin.

As tabulated recently by the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, such resolutions have already passed at such colleges as Loyola University, in Chicago; Wesleyan University; Oberlin College; The Evergreen State College; University of Toledo; Stanford University, and the University of California campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles and Riverside. The February vote at UC Davis was overturned by another campus body, which said it was not within the purview of the student government to approve such a measure. New York University professors and students are gathering signatures for a similar effort.

In one sense, these referenda and student government votes are exercises in student vanity. Not one of these schools has a board of trustees that appears to be interested in considering divestment, whatever their students say. But as political exercises they are taken seriously by those involved on both sides as tools for influencing the views of students.

The experience of students like Kathleen Ma, a Princeton freshman, suggests why this is so. “Hearing and talking to some of my classmates who are clearly very passionate about this issue has made me more aware of the issues, and I’ve definitely noticed an increase in campuswide interest in this issue,” she said.

Just what influences the vote of students with little prior involvement in Middle East issues, however, can be quite personal, for all the intensity of the posters, advertisements, campus paper editorials and social media invective.

One senior student, who spoke only on condition that he not be identified so as to keep his vote private, said his decision to oppose divestment was based on the enthusiasm of friends. “What really swung me was several very, very close Jewish friends of mine who felt very, very strongly that divestment would send the wrong message,” he said. “On an issue where I am a little more ignorant than perhaps I should be, the fact that several people took time out of their days to meet with me and talk with me about how it urgent it felt to them and why my vote mattered certainly helped sway my decision.”

In the end, El-Dirany was pleased with the campaign, for all its tensions, even though his side lost. “Even if it didn’t pass, we’ve changed the campus,” he said. “I don’t think anyone’s ever been talking about Palestine or Israel so much ever since divestment came up. We made people care about the issue…. The environment’s changed, and there will be more progress made later on.”

But Sam Maron, a sophomore involved with Tigers for Israel, an anti-divestment group, saw negative effects of the referendum on campus politics.

“While it created some productive conversation, it created also a lot of unfortunate campus polarization,” Maron said.

The No Divest Campaign, which was the organized umbrella group of opponents of divestment, posted the election results with a condemnation of the referendum.

“We hope the rejection of this referendum will mark the last time the student government puts to a vote such a divisive issue so far outside the scope of campus life and beyond the purview of student opinion,” the statement said.

Meanwhile, Horvath said that the Princeton Divests Coalition had both reached out to and been contacted by other schools looking to initiate similar campaigns.

“We see a lot of hope not only for Princeton, but for schools across the country,” she said. “We know that the name of Princeton carries weight in the broader university context and the broader U.S. context. So we do want this to spark other initiatives at other schools.”

Contact Logan Sander at [email protected]