Praying at A Jewish Tomb in Shadow of ISIS

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Al Qosh — Back when they still lived in Iraq, Kurdish Jews had a famous saying about the ancient synagogue believed to house the tomb of a biblical prophet in this beleaguered town on the high northern plateau of Nineveh province.

On Shavuot they said, “He who has not made the pilgrimage to Nahum’s tomb has not yet known real pleasure.”

This past Shavuot I was part of a small group that may have been the first in more than 60 years to celebrate this holiday at the synagogue.

Though she had been there at least twice before, my wife did not want us to travel to Al-Qosh this time. The quiet, serene village of mostly Assyrian Christians is known for its many stone homes, its seventh-century monastery and its many ancient churches. But it lies a mere 34 miles from Mosul — since June 2014, the Iraqi base for the terrorist organization par excellence known as the Islamic State. The village’s current population of some 10,000 to 20,000 has been swelled by internally displaced people from nearby villages taken over by this force of terrorists.

Several months ago, most Alqoshniyes fled for safety to Iraqi Kurdistan, the neighboring semiautonomous northern region known for its tolerant, relatively open society and for the Peshmerga, a proven fighting force against the Islamic State. It has been only a couple of months since most inhabitants of Al-Qosh and other surrounding villages have returned, following the liberation of the surrounding area by a combination of Peshmerga, local Christian militias and U.S.-led coalition air strikes.

Still, Al-Qosh sits in close proximity to the ongoing fighting, and those who live even closer to Mosul have not been able to return to their homes. Indeed, much of the Nineveh Plains is either still under the Islamic State’s control or its threat.

This was our second time visiting Iraq. Initially, my wife and I moved to the Kurdistan Region for a year in August 2013, five days after we got married, to teach English and social studies at an elite private school in Erbil, Kurdistan’s regional capital. Deeply interested in refugee and immigration issues, my wife dedicated much of her free time to volunteering at a nearby Syrian Kurdish refugee camp, where she was greatly appreciated and warmly received.

This would be my fifth visit to the shrine of Nahum, a prophet of the Israelite exile who famously predicted the destruction of Nineveh, the Assyrian Empire’s mighty capital, in the seventh-century B.C.E. For me, it was just as meaningful as the first time. Walking into the dark and halfway toppled synagogue was an emotional experience: Each time I walk around in this dilapidated structure I graze my fingers over the ancient stones and pillars, and at once I am transported to a different time, when Kurdish Jews still lived here, prior to Israel’s establishment in 1948. I hear the clamor and jumbled chants of a prayer service mixed with joyful cacophonies of men, women and children celebrating, laughing, singing and dancing in their colorful traditional clothes. I don’t want to open my eyes.

On this most recent pilgrimage to the synagogue, a small part of me was nervous, but not due to fear; I felt that something was pulling me to go to the synagogue on Shavuot and reaffirm some semblance of a Jewish presence in a very Jewish place, 30 miles from the Islamic State — a symbolic act of spiritual resistance.

This 2,500-year-old synagogue is the only Jewish structure still standing in northern Iraq. It is the most prominent and visible reminder still standing of Kurdistan’s 3,000-year-old Jewish history. Yet it is not well known to the Iraqi public. It was a good friend — an expat who had been living in Kurdistan for several years — who first told me about the synagogue’s existence. I went, and was entranced.

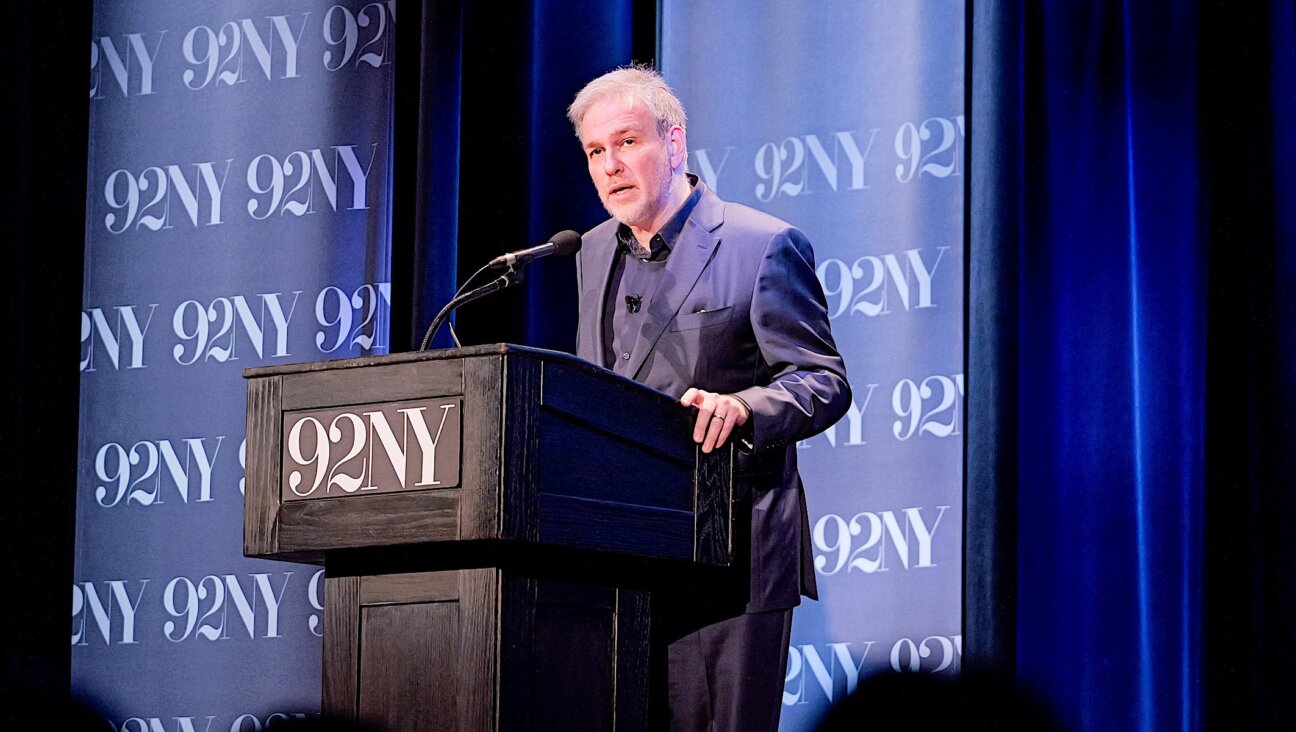

The author at the tomb of the prophet Nahum, during Shavuot. Image by Whitney Kweskin

Though the synagogue is half rubble and long emptied of its most important articles and artifacts, it is still easy to imagine the site in its original splendor; the building is quite large and once included a second floor, as well as a large courtyard. In the center of the worship area stands an ornate, four-sided gate that is easily opened. Inside the gate is a wooden box covered with multiple layers of green cloth. It is in this place that, according to tradition, the remains of Nahum lie — or used to. Over the centuries, successive attacks on the synagogue led the Jewish communities’ Assyrian Christian neighbors to remove the site’s remains for safekeeping in a nearby church. In any event, what actually lies in the resting place at either site is, at the least, a matter of legitimate historical debate. While there were initial attempts to renovate the synagogue several years ago, nothing substantial has materialized. The structure remains as precarious as ever.

Kurds and Jews have a fascinating shared history with roots in ancient times. Many date Jewish presence in what is today Kurdistan to the eighth-century B.C.E., when the Assyrian Empire — ancestors of the same friendly Assyrian Christians who are today under threat — conquered the Northern Kingdom of Israel. The conquerors took thousands of Israelite captives into exile, to the “cities of the Medes” — that is, the predecessors of the Kurds. There was even a Jewish kingdom based in Erbil in the first and second centuries, called Adiabene, or Hadyab. During the Roman occupation of Judea, the kingdom’s rulers sent provisions, weapons and even soldiers to help their fellow Jews. After Judea fell, the Romans headed east, and when the Jewish emperor of Hadyab was overthrown, his family and advisers fled to Hamadan, in neighboring Iranian Kurdistan, where the reputed shrine of Mordechai and Esther remains today.

I first focused on the Kurdish narrative academically, but this grew into something much greater than I ever anticipated. Though overwhelmingly Muslim, most Kurds stress their Kurdish identity strongly, and some of their cultural norms diverge from orthodox Sunni Islamic practices.

Newroz, for example, the Kurds’ traditional new year holiday, parallels the pre-Islamic Persian new year celebration at the start of spring and is the Kurds’ most important holiday. It predates Islam by at least 2,000 years, and features many pre-Islamic customs, such as large bonfires and co-gender dancing. Additionally, the centerpiece of the Kurdish national flag is a 21-ray golden sun — a symbol of the pre-Islamic, Zoroastrian and Yezidi minority religions. For centuries, Islam in Kurdistan has been known for Sufism rather than for radicalism. This is still the case today.

•

It was not until after we had purchased plane tickets for our return trip to Kurdistan that I realized we would be able to mark Shavuot there. Though not particularly religious, I have developed an attachment to this holiday, which celebrates the Jews’ acceptance of the Torah from God at Mount Sinai and is observed by the study of Torah far into the night, until dawn.

Shavuot also marks a terrible tragedy in modern Iraqi Jewish history: It was the eve of Shavuot in 1941 when the infamous Farhud ravaged Jewish Baghdad, Iraq’s capital city to the south. It was the largest pogrom the community had seen in centuries, and a major turning point in the people’s hastened expulsion from Iraq. At this time, Baghdad had a sizable Jewish population, nearly one-third of its inhabitants. When the dust settled, several hundred Jews had been killed, raped and wounded, and hundreds of Jewish-owned shops were damaged or destroyed. This pogrom included many non-Jewish victims as well: many Muslims and Christians were injured or killed defending their Jewish neighbors and friends.

In earlier times, Shavuot was a pilgrimage holiday. For centuries, Jews from far and wide used to travel to the synagogue in the beautiful mountain town of Al-Qosh for more than a week, celebrating and reading the books of Ruth and Nahum, enacting the post-apocalyptic War of Gog and Magog on a nearby hill, and rejoicing with great fanfare. Humbled and eager, my wife and I set out to fulfill this local mitzvah on our own pilgrimage to Kurdistan.

Up until the night before we left, we were not sure we would be able to make it to the synagogue, as we had no driver. But that night, we met an acquaintance of a close friend, an Assyrian Christian who himself is originally from Al-Qosh who agreed to drive us. A local journalist by profession, he asked that his name be withheld out of fear that he could become a target of extremists. He showed us his extensive portfolio, including hundreds of pictures and videos of historical Jewish landmarks throughout Iraq. Among these were holy sites such as the purported tombs of the prophets Ezekiel and Daniel, in Kifl and Kirkuk, respectively. Today, they are unsafe for Iraqis to visit, let alone non-Muslims and Westerners.

The trip itself proved unexceptional. Just before we left we were joined by another American Jewish expat, a teacher from the West Coast. We talked Kurdish and Jewish politics, culture and history, and tapped our fingers to Shakira’s latest album, as we rode along.

At the handful of standard checkpoints Peshmerga guards enjoyed speaking English to the three ajnabin, or foreigners, in the car. But the fact that there was a war happening nearby remained in the back of our minds. It was between the small, ancient cities of Kalak and Al-Qosh that we saw plumes of smoke some distance away. For months, coalition planes have been targeting the Islamic State group in areas close to where we were traveling, and though we did not hear any explosions, it was an eerie reminder not to take this trip lightly. How many times had this happened since Nahum’s prophecy of destruction, I wondered?

Image by Benjamin Kweskin

Then, suddenly, we were blocked. At the entrance to Al-Qosh, an Assyrian Peshmerga told us that foreigners now needed official papers. This was never the case during any of my previous visits. The new proclamation seemed to have come out of nowhere. I held my breath while the guard and our driver talked for what seemed like an eternity. In actuality, their conversation lasted just a couple of minutes. The driver mentioned that he was a local, and this turned out to be our magic ticket. The guard politely waved us through as I exhaled and felt overcome with excitement as we drove into the town.

Al-Qosh is known to have many supporters from the Iraqi Communist Party, and as we entered I saw, from a distance, the iconic red hammer and sickle flag. It is said that Saddam Hussein punished the people of Al-Qosh for their leftist ideology and denied them much infrastructure and up-to-date resources while he was in power. Built at the foot of the mountains, Al-Qosh, thanks to its relative isolation, is a village in which many residents still speak Aramaic. Older townsfolk dress in traditional clothing, nearly indistinguishable from the attire worn by residents in the nearby Kurdish city of Dohuk. Men wear brown or gray-striped shirts and striped baggy pants; black-and-white-checkered scarves cover their heads.

Driving through the narrow streets, we quickly arrived at the synagogue, easily recognizable by the corrugated bright red roof constructed by a Western businessman with strong ties to Iraq. The roof serves to preserve the painted Hebrew writings on the synagogue’s pillars and plaques, which have become worn and harder to make out due to decades of weathering.

The four of us walked excitedly to the home of Nasir, the man who watches over the synagogue. He recognized us, despite it being more than a year since we had seen him, and gladly walked us over and opened the padlocked gate to the courtyard. Nasir’s family has been watching over the synagogue for two generations, at the request of the last rabbi in Al-Qosh, who left with his family for Israel in the early 1950s.

After entering the building, the four of us walked around by ourselves for a few minutes. The two Jewish males — myself and the teacher from the West Coast — donned kipot. My wife took out her two candles as I readied my Israeli-purchased yahrtzeit candle to usher in this auspicious holiday. Our new American Jewish friend, making his first visit to this site, was overcome with emotion as he entered the building. Largely talkative during the car ride to Al-Qosh, he quickly grew silent and contemplative.

After the lighting, standing next to the prophet’s tomb I read aloud the prayer recited when people arrive at the tombs of tzaddikim, righteous people. Overlooking us as I read aloud was a clear Hebrew plaque, one of several dispersed throughout the synagogue, detailing its history and significance as Nahum’s burial site. After a calm silence, the three of us quietly parted ways, stretching out to different corners of the shrine, searching for our own personal prayer.

Bidding farewell was an emotional and bittersweet experience; I wanted to somehow protect the site and sit there for hours, daydreaming about joyous prayers, singing and dancing in colorful outfits. I wanted to continue daydreaming about hearing the Torah being taught to those who had gathered for such a celebration. I thanked God we were able to travel in peace, and asked that we be returned safely as well. After my simultaneous prayers and daydreams concluded, I wondered when I would return to such a holy place, and if the synagogue would last another year.

Contact Benjamin Kweskin at [email protected]