Meet The Lonely Ukranian Jew Fighting His Country’s New Fondness For Nazis

Ukranians are fighting against Russian control by rehabilitating historical anti-Communists — even if they were also Nazis. Image by Getty Images

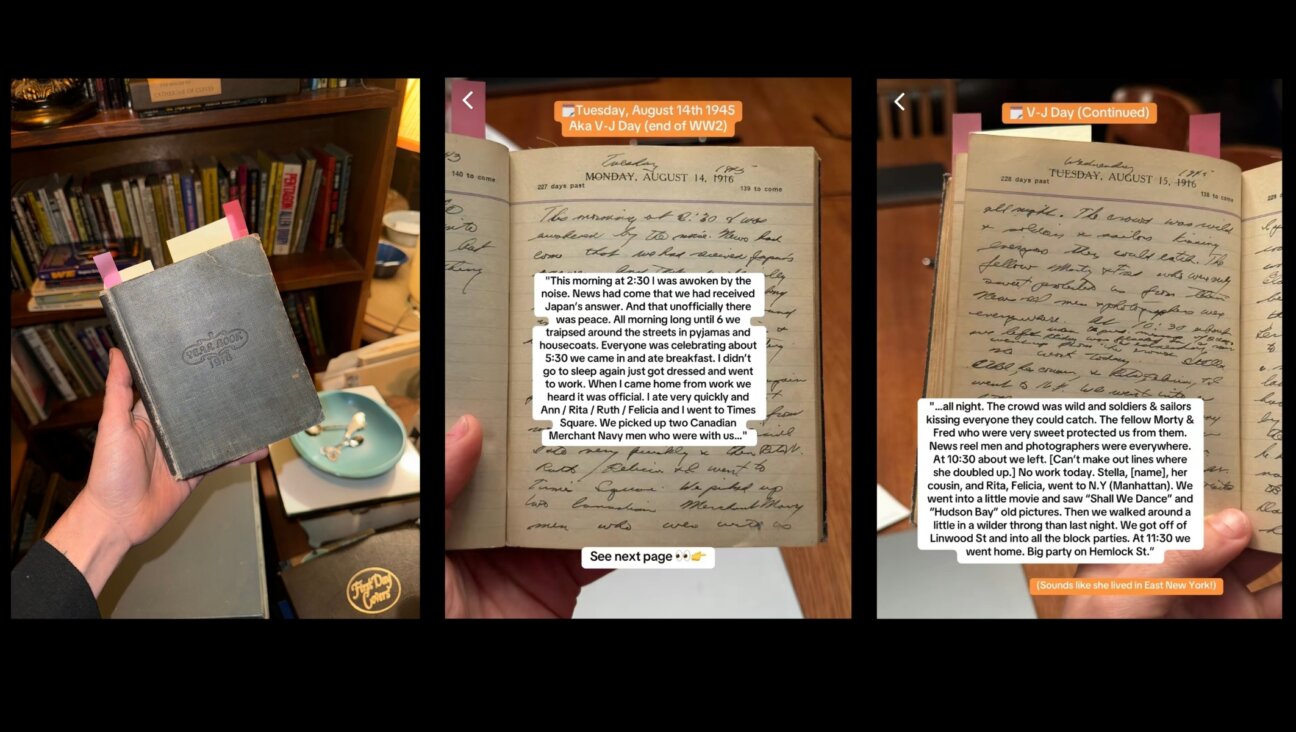

Eduard Dolinsky went online about a year and a half ago and saw an image that shook him to his core. A large crowd, some in Nazi uniforms, was parading in the Ukranian city of L’viv to commemorate the establishment of a militia loyal to Hitler.

“Division Galicia – the heroes of Ukraine,” the marchers chanted as they walked.

As head of one of Ukraine’s leading Jewish advocacy groups, Dolinsky was livid at the idea of celebrating Nazi collaboration. For the same reason, he could try to do something about it.

“When the government, state and civil society start to promote these organizations as heroes and those who fought for Ukrainian independence and whitewash their participation in the Holocaust actively and aggressively, I decided that my obligation and duty was to speak out against this,” Dolinsky told The Forward. “This is a denial of basic moral sense.”

Eduard Dolinsky Image by facebook

Today, Dolinsky, the 49-year-old director of the Ukranian Jewish Committee, is immersed in a campaign against the valorization of the SS as anti-Communist heroes.

“When I was a kid someone told me that I’m a Yid,” recalled Dolinsky in a recent interview with the Forward. “I came home and asked my mom what it meant. She told me that we are Jews and we are different, don’t pay attention. For a long time afterwards I was confused and ashamed that I’m different and not like other kids.”

Ukrainian Jews are about 0.1% of the country’s 44 million people.

The country, which sits on the Black Sea, is bordered by Russia on its east, Belarus to the north and various eastern European countries to its west. Its relationship with Russia has dominated its politics for hundreds of years; it was a member state of the Soviet Union, and since its dissolution, the two countries have experienced periods of cooperation, tension and even armed conflict. The current government has no diplomatic relations with Russia and is actively resisting its influence. That’s where the Nazis — and Dolinsky — come in.

The current anti-Russian government has enlisted history in its cause, and has embarked on an active campaign to suppress Communist symbols and to rehabilitate people and groups that fought against the Soviet Union — no matter what crimes they may have committed against the Jews.

Born in 1969 to an active, if non-observant, Jewish family in the former Polish city of Lutsk in the country’s northwest, Dolinsky served two years in the Soviet Air Forces and was discharged shortly before the collapse of the Soviet Union.

While many Ukrainian Jews fled the country at that time, the pugnacious Dolinsky decided to stay. He said that he has been asked many times over the years, mostly by American Jews, about why he remained behind.

“First of all, you were born here, you were raised here, your son was born here, your parents are buried here, so all your heritage and legacy is here and this is the country of your language and your friends and family. You can play a role here. I can be much more effective in life and in my professional activities here than anywhere abroad,” he said. Dolinsky is married, and the father of a 25-year-old son who studied in Israel and works in finance in Ukraine.

It was during and just after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when anything seemed possible, that he first became actively involved in efforts to rebuild his country’s moribund Jewish communal life, first serving in administrative roles in the newly established Jewish Foundation of Ukraine and the All-Ukrainian Jewish Congress before moving on to establish the Ukrainian Jewish Committee together with minor oligarch and lawmaker Oleksandr Feldman.

Dolinsky is known as a firebrand, willing to speak out harshly against perceived threats to the community even when others prefer a more conciliatory approach.

Asked if he finds inspiration in the example of former Anti-Defamation League leader Abe Foxman — an American crusader against anti-Semitism and bigotry more broadly — Dolinsky replied in the affirmative.

“I think yes,” Dolinsky told the Forward.

His high profile, bolstered by the use of social media and his close contacts with journalists, belies his small staff (only three full time employees and twenty volunteers spread across the country.) His posts on Facebook are often picked up and used as the basis of stories in outlets such as The Jerusalem Post and the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. He also collaborates with the ADL, American Jewish Committee and National Coalition Supporting Soviet Jewry.

Now, Dolinsky is taking aim at his government’s public awareness campaigns that praise organizations that collaborated with the Nazis and engaged in the widespread ethnic cleaning of Jews and Poles, such as the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and its militant offshoot, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

He faces a major obstacle, however, in Ukraine’s “Decommunization Laws,” which banned a slew of Communist — and some Nazi — symbols. The Decommunization Laws only list a limited number of Nazi symbols whose use is prohibited. That means by law, some are allowed, and that means Dolinsky’s quest is a bit quixotic.

He believes that the Galician Division’s symbols should be included in the ban because the unit was a part of the SS and its members “all made an oath to Hitler.” And even if their logo ends up being declared legally acceptable, he isn’t deterred. “First of all, I want to bring attention to the issue of Nazi collaborators and those who perpetrated the Holocaust,” he explained.

An avid reader who devours books on Jewish history, Dolinsky is one of a class of what can be called professional Jews, people whose entire Jewish identity is wrapped up in their work for the community.

“It’s like an inseparable part of my life,” he said of his work. “It’s my whole life. I can’t even imagine myself outside of this. The work isn’t just work. The Jewish community isn’t about the work as a profession, it’s a passion that haunts all your life. It’s not about nine to six. It’s 24 hours, seven days a week.”

As a representative of the UJC, he makes frequent media appearances, taking to the airwaves to make arguments that strike at the core of Ukraine’s self-image.

In 2017 he publicly (and unsuccessfully) demanded that the local state prosecutor prosecute organizers of the SS march for their “malicious and demonstrative violation” of the law. Volodymyr Viatrovych, Dolinsky’s longtime nemesis and the official in charge of implementing Ukraine’s national memory policy, maintains that that the Galicia Division’s symbols are not legally problematic.

And while many Ukraine scholars are critical of Viatrovych’s glorification of Nazi collaborators, most say he’s right about what the Decommunization Laws do and do not prohibit.

Refusing to accept Viatrovych’s explanations, Dolinsky escalated their dispute, publicly calling on Ukraine’s national prosecutor to bring a lawsuit against Viatrovych himself for violating the law against Nazi glorification. It was not the first time the two had tangled.

Only weeks earlier, Dolinsky had written a caustic op-ed in The New York Times in which he accused the Ukrainians of “whitewashing” history and linked such revisionism to a growing “climate of anti-Semitism.” In response, Viatrovych took to Facebook to accuse Dolinsky of making up Ukrainian anti-Semitism and selling it “in the country and abroad to everyone who will pay for it,” calling him even worse than those who “made money by hiding Jews from Nazi persecution.”

Given their history and diametrically opposite points of view, it is unsurprising that Dolinsky would end up ratcheting up the conflict. While not suing Viatrovych himself, Dolinsky is backing a lawsuit against him alleging that Viatrovych, in his capacity as a civil servant, violated a Ukrainian law prohibiting him from publicly interpreting the law. There is a Ukrainian law prohibiting civil servants from issuing pronouncements on legal issues that are in the jurisdiction of the courts, and Dolinsky believes that by claiming the SS Galician Division’s symbols are legal, Viatrovych has broken that law.

Several Ukrainian Jewish groups, including the Jewish Confederation of Ukraine, have expressed support for Dolinsky’s efforts, although privately some have expressed doubts about his harsh rhetoric and confrontational style.

“Some people think he’s too confrontational and uses intemperate language. The message gets lost,” he said one longtime observer of Ukrainian Jewry who spoke to the Forward on condition of anonymity.

But Dolinsky says that he is compelled to continue.

“When you say the guy who murdered a Jew is a hero, this is the second murder of Jews,” he said, explaining that whitewashing the legacy of those who slaughtered Jews is tantamount to killing them all over again.

Sam Sokol is a freelance journalist based in Israel. A former Jerusalem Post and IBA News correspondent, he is currently writing a book on the destruction of the Jewish communities of eastern Ukraine.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO