Ahead of Super Tuesday, Southern California’s oldest temple is politically diverse, yet spiritually united

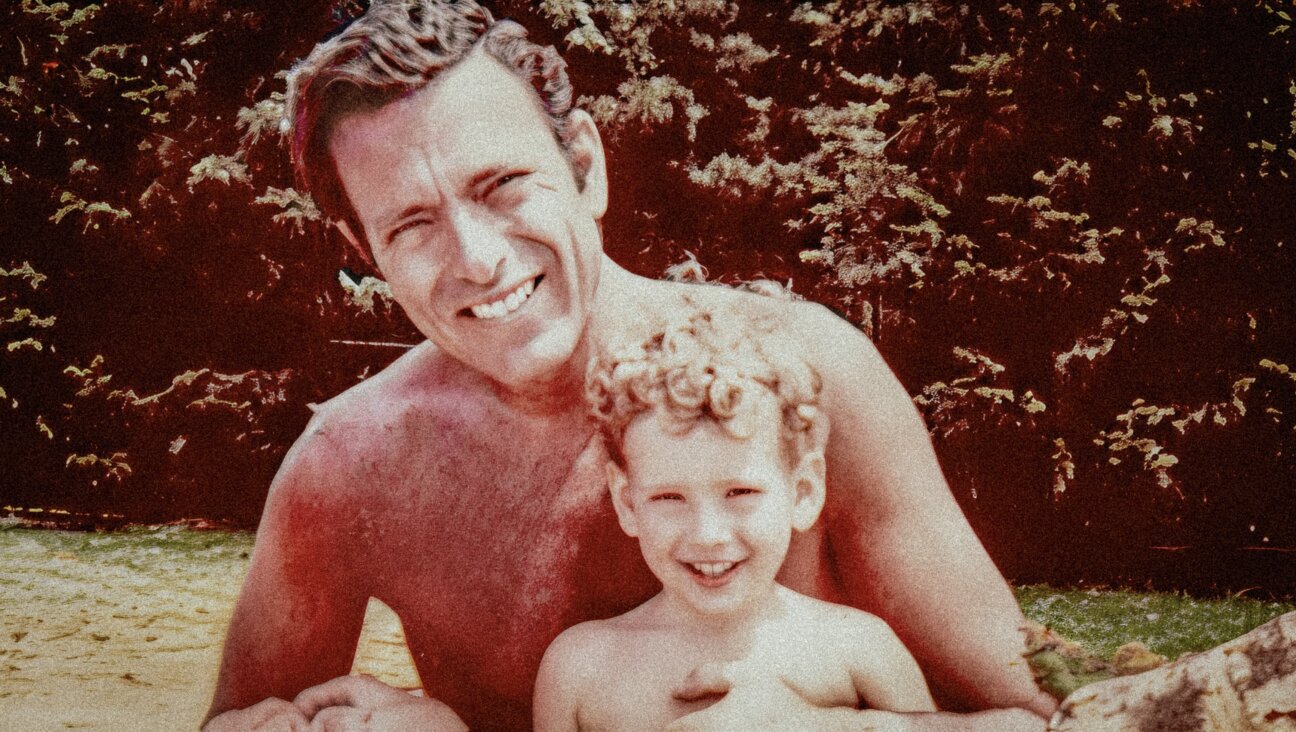

California’s oldest synagogue is politically diverse and spiritually united. Image by Louis Keene

The weekend before Super Tuesday was Climate Change Shabbat at Congregation Emanu El, a Reform synagogue located just outside of San Bernardino in Redlands, Calif. The congregation’s Sisterhood created a special Shabbat service for the occasion, during which the women took turns at the lectern describing the sacrifices they were making for the sake of the planet: giving up meat, turning up the thermostat during the summer, switching out lawn sprinklers for drip irrigation.

The question of survival, and what it costs, is a familiar one to this group. Emanu El is the oldest congregation in Southern California, with roots going back to 19th century San Bernardino, where its complex — a sanctuary, plus a library and offices — occupied an entire city block for 50 years. But the city has been in decline since the mid-1990s, and when people’s cars started getting broken into during services, Emanu El sold the property and headed for the hills, where many younger members were already living. Temple president Stuart Sweet said the congregation lost a third of its membership in the relocation. The new building, opened in 2013, is smaller, but not small, with a sanctuary whose capacity is 300, and separate spaces for a social hall and Hebrew school.

What remains is what Sweet calls “an exciting tapestry” of demographics, personalities, and politics amid a revival led by Rabbi Lindy Reznick, who arrived two years ago as the first female head rabbi in the congregation’s 127-year history. The community still faces a tenuous future, but it is becoming a center of Jewish learning and observance that unites people in one of the most polarized areas in the state. Emanu El sits right on a political faultline. Redlands flipped Democrat in 2008, but “go one more exit on the 10 Freeway, you’re in red territory,” Sweet said. “We have families who are about as red as you can get, and families who are just about as blue as you can get.”

Sure enough, pull aside Emanu El congregants at Kiddush, the light meal after services, and you’ll find someone behind nearly every name on Tuesday’s ballot. Roberta Gold, 81, has been a member for 50 years and is backing Joe Biden. “He’s going to bring the party together,” she said.

Her husband Phil hasn’t decided yet, but knows he’s voting Democrat. “The Democratic party is more consistent, particularly these days, with Jewish values,” said Phil, 83. “One of the reasons [anti-Semitism] is on the rise is the current administration encourages polarization and tribalism, and gives voice to people who say things that are unkind, and mean, and divisive.”

Debra Holder, 50, is leaning Elizabeth Warren, but hasn’t fully committed because she doesn’t see a path to victory for the Massachusetts senator. “I think Netanyahu has to go, and we have no control over that, except for getting Trump out,” she said. “I think that part of the anti-Semitism that’s abounding in this world has to do with Netanyahu’s policies, and I think that Trump helps prop him up. You can say it’s pro-Israel, but I think in pushing forward that very anti-Palestinian agenda, it’s really causing more anti-Semitism in the world.”

Leslie Soltz, 74, mailed in her vote for Amy Klobuchar: “I believe that our candidate should be under 70 years old.” Her husband Bill will vote for any Democrat but Bernie Sanders, and shocked his wife by vowing to pick Trump over Sanders in a general.

“At least he’s pro-Israeli,” he said. “I can’t stand the way he acts, I can’t stand the way he is, but his ideas aren’t so way out of line.” Sanders, on the other hand, is “pro-Palestinian,” Bill said. “I’m not pro-Palestinian, I’m pro-Israeli. Palestinians have every opportunity to make peace, and they don’t make peace. And the Israelis want it!”

There are outright Trump supporters noshing, too: Gillian Block, a newer member, called the president “the Golden Boy.” She described living under constant threat of violence in her native South Africa, and said that experience informed her politics. “When you look at all the candidates, he comes across as the strongest one, the biggest protector out of all of them,” she said. “Are you going to hide behind Bernie when there’s trouble? I don’t think so. In a crazy, nutjob world, when you have seen things, you go to the biggest, strongest one.”

Kathy Trainor, 72, a retired antiques store owner who has been a member for around 25 years, thought she was only a handful of other conservatives at Emanu El. “I usually keep quiet, as I am a big minority in this congregation,” Trainor said. “I just don’t discuss politics here, and it works.” During a recent Yom HaShoah event, a person stood up and said that their family felt like pariahs because they had voted for Trump.

But Holder and Block and Margie Henkin, a Bloomberg voter (“He’s smart. He’s not going to screw us over.”) are all seated around the same table at Kiddush, and they stay long after the last tray of fruit has been cleared to talk politics and reminisce about the synagogue’s history.

From a strictly numerical perspective, the synagogue needs them all. There are simply not that many Jews in Redlands and San Bernardino — only a few thousand in the metro area identify as part of a Jewish community, according to a 2018 study by the Jewish Data Bank. Nor do more seem likely to come. Since the Norton Air Force Base closed in 1994, eliminating thousands of high-tech jobs overnight, San Bernardino has been staring down insolvency, and Redlands is too suburban to sustain much growth.

That’s why Reznick has sought to increase headcount and bridge the generational divide by reaching out to local LGBTQ Jews, college students and Jews of color. She helped organize Redlands’ first gay pride parade and is out herself. Expanding the tent to make people of all backgrounds feel welcome can sometimes be a balancing act, however.

Inclusion has been central to the synagogue’s mission since the San Bernardino days, but that has a different meaning in a part of the state that’s more purple than blue, “We’re not West L.A.,” Reznick said. “It’s different what our movement gets behind and what our congregation gets behind than if we were in a very liberal area.”

Reznick and Sweet insist that their congregation’s platform and programming are grounded in values, not politics, but attributing climate change to human activity, which the Sisterhood does directly during its service, is only apolitical to most people, not all of them. Presenting ostensibly progressive ideas as universal, even genuinely, only works some of the time.

For example, Reznick acknowledges that the pride and extroversion of the LGBTQ community has at times been challenging to some of the older members, and Trainor admits being one of them. “It’s different for me,” Trainor says. “I am more of the ilk of the older generation, in terms of values and preferences and ideas. That’s why it’s good that I’m the age I am.” She laughs. She’s more flexible than she lets on: Despite questioning the science that blames humans for global warming, Trainor recited a poem during the sisterhood’s program — to support her friends, and because she counts herself among them. And she has been able to convey some of her values to the youth in lessons at Emanu El’s Hebrew school.

What keeps Trainor coming back to Emanu El are the people and the tradition, but also her place in the big picture: preserving the viability of local Jewish life. She opposed withdrawing from San Bernardino a decade ago but has since come around to it. The community’s survival, she said, remains a central concern. “We’ll lose our identity, and our sense of worth, and the good things that we do as a community, if we do not stick together,” she said. “We’ve got to change, or we’ll die. And we’ve changed.”

To meet the shifting Jewish demographic of Greater San Bernardino, the congregation has relocated and installed a new rabbi. But it has also adopted smaller changes ranging from the technical (switching prayer books ) to the practical (introducing faster young-adult services once a month) to the philosophical (emphasizing interfaith connections).

What has resulted is a home that makes Shayna C., who was one of the only young adults at Kiddush Friday night, bullish on the community’s future because she knows she’ll be creating it.

Shayna, 22, is converting, and the issues she’s most passionate about are healthcare and climate change; she was undecided going into Super Tuesday. She knows she doesn’t agree with all of her predecessors’ opinions. But the community that cemented her connection to the faith would not exist today without them, and Shayna would be the first to tell you that.

“It’s important to me that [Emanu El] stays for a long time in the future so that I can carry it on,” said Shayna, who asked to keep her last name private, citing a concern for her personal safety. “Maybe this is cheesy, but it’s L’dor Vador, right?” she asked, referring to the ancient Hebrew phrase that means “from generation to generation.” “And right now I’m receiving, but if I keep on in the community, and grow in activism and learning and Jewishness, then at some point I get to pass it on to the next generation of Jewish young people.”

And by that, Shayna said, she means people “who need the same things that I’m getting from it right now.”

Correction, March 5, 4:50 p.m.: An earlier version of this story said Congregation Emanu El is the oldest synagogue in California, but it is the oldest synagogue in Southern California, the 10-county area dominated by Los Angeles and San Diego.