Yiddish Coney Island

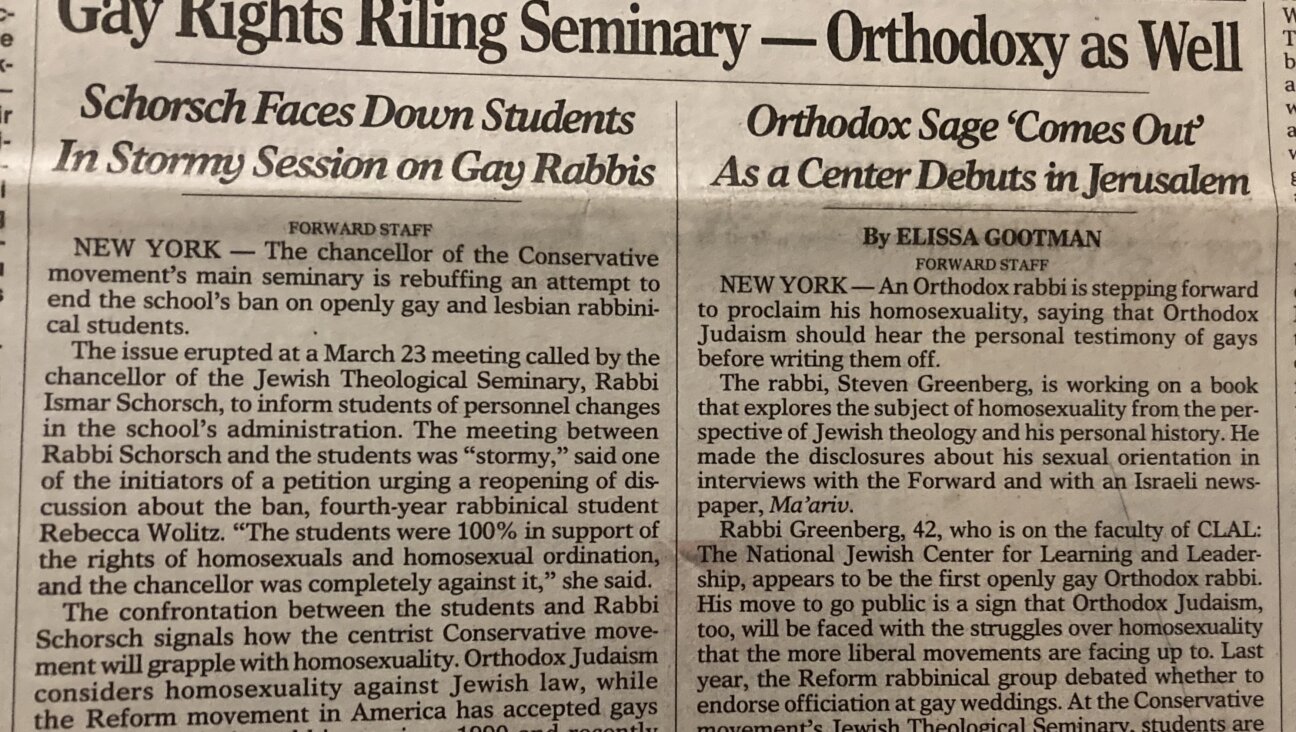

Scene at Coney Island. May 4, 1930 Image by The Forward

The Forward is one of 57 libraries, museums and city agencies, contributing to a new app called Urban Archive, helping make historical materials engaging and accessible. To celebrate the beginning of summer, we highlighted the Brooklyn beach-neighborhood of Coney Island, one of the most iconic New York places. Read all about its fascinating history as a getaway for Jewish New Yorkers. For even more, check out our Urban Archive collection.

Coney Island, known as the “poor man’s paradise” is a New York City beach district that held a special place in the hearts of America’s Yiddish-speaking Forward readers who arrived in New York from Eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Known for its massive summer crowds, commemorated in Victor Packer’s Yiddish poem “Coney Island,” the beach is uncharacteristically empty in this 1930 Forward image.

In Packer’s words, translated by Henry Sapoznik:

Zamd un mentshn

mentshn un zamd.

“Sand and people.

People and sand.

On the sand a world of people.

On the people a sea of sand…

There’s no room, you’ll have to stand”

The neighborhood is situated on the southern coast of Brooklyn and its beachfront, boardwalk, amusement park, shows and carnival atmosphere attracted the city’s immigrant workers longing for a brief escape — or staycation — from the urban heat of Manhattan since tenement-era New York.

Amusement park rides listed in the Forward as early as the 1920s, give a glimpse into the atmosphere: The Human Whirlpool and Witching Waves!

Called ‘the world’s playground,’ Coney Island was home and a resort-type destination for immigrant groups from all over the globe. The Jewish experience was even made famous by Yiddish accented mimic and comedian Fanny Brice in her song Mrs. Cohen at the Beach. Brice, a Jewish-American comedy-performer, lived in the Coney Island neighborhood of Seagate and became a radio star.

Seagate, at the neighborhood’s tip, was also home to Yiddish poet Aliza Greenblatt, who was also famously the mother-in-law of folk-singer Woody Guthrie. Nobel Prize-winning Forward writer, Isaac Bashevis Singer, lived there when first arriving.

For world-weary New Yorkers, it was a magical place to briefly forget their troubles. In 1929, the Forward called it a place “where humanity congregates in a collective oblivion of the heat and diurnal worries.”

All summer, the boardwalk and amusement park featured games with prizes, twirling rides, freak shows, and vendors selling hot dogs and sweets. In 1939, the Forverts invited beachgoers to “khap a nash” — grab a snack at “Feltmans,” an old favorite restaurant that has now been revived. Advertised as a local favorite dining locale for over 66 years, dinner was only $1.50.

But while it was known mostly as an exhilarating place to visit, many called it home. During the summers many boarders moved in either to live at the beach or to work its attractions. One 1929 Forward article claimed that “a Coney Island apartment has more beds per square foot than any other community in the world.”

In July 1948 The Forward advertised a lovely bakery on Mermaid Avenue. With five rooms it was up for offer. “A bargain” the classified ad read, due to “ family troubles.”

Coney Island, no stranger to oddball couplings, also came up in a 1924 letter to the editor in The Forward. The writer had been staying at a friend’s beach house when he accidentally walked in on his friend’s wife “in a very compromising position with the boarder.” While it’s hard to imagine Editor Ab Cahan envisioning today’s “throuples” or whatever the Yiddish word for “polyamory” is, as a socialist, he surely knew about fraye libe (free love) and responded that the writer should not tell his friend about the wife’s indiscretion. His reasoning was that “the sum total of unhappiness in the world that has been caused by kind and helpful friends” cannot be underestimated.

Coney Island’s beach, while refreshing for sure, was also where “beauty and crudity go hand in hand and launch a united front,” according to Packer. Some Jewish immigrants even found employment as sideshow performers while woodcarvers used their Eastern European honed skills to fashion wooden horses for Coney Island’s carousels.

Guthrie’s ode to the ‘hood, “Mermaid Avenue” calls up sweet n’ sour local images you’d see merely by taking a stroll outdoors:

Mermaid Avenue that’s the street

Where the lox and bagels meet,

Where the hot dog meets the mustard

Where the sour meets the sweet;

Where the beer flows to the ocean

(Where the halvah meets the pickle)

Where the wine runs to the sea;

Why they call it Mermaid Avenue…

There were tens of thousands of year-round dwellers as well, many of them Jewish. A 1926 article called it “as much a Jewish community as the Bronx.” Perhaps the most famous depiction of everyday Jewish American life in the area was Neil Simon’s semi-autobiographical play “Brighton Beach Memoirs” about one family’s Depression-era struggles.

By 1919, there was a big enough audience that the New Brighton Theatre — once located on Ocean Parkway’s expansive boulevard — converted itself into a Yiddish theater. And in August 1923, the Forward published an entire page of photos of frolicking beachgoers. beachgoers.

Despite its storied popularity with people of all walks, Coney Island was not free from racism or anti-Semitism. For a time Jews were barred from Seagate and adjacent Manhattan Beach.

“The Jews,” said 19th-century developer Austin Corbin “drive off people whose places are filled with a less particular class.”

There were also games where people lined up to throw or hit racist depictions of African Americans for prizes. African Americans also had to use segregated segregated bath houses and were discouraged from occupying certain sections of the beach.

However by the 1920s, the population of Coney Island and surrounding neighborhoods were actually mostly made up of first and second-generation Jewish Americans and later of Holocaust survivors.

The district’s Jewish character evolved further beginning in the 1970s with the arrival of a wave of Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union. It was still a typical weekend activity for local families to hit the beach on the weekends when fireworks were displayed.

The beach, boardwalk and rides still attract New Yorkers today but Coney Island is also known for its modern institutions. One of the most famous attractions of the New York City calendar is the annual Mermaid Parade celebrating the art, culture and history of Coney Island.

In the tradition of Isaac Bashevis Singer, today’s lovers and scholars of Yiddish still head out to Coney Island to soak in the atmosphere, seek relief, and find inspiration.