Orthodox women built businesses and friendships online. They’re being told to sign off.

In the wake of rallies that drew tens of thousands and railed against social media usage, some say their communities’ expectations for women are getting more strict.

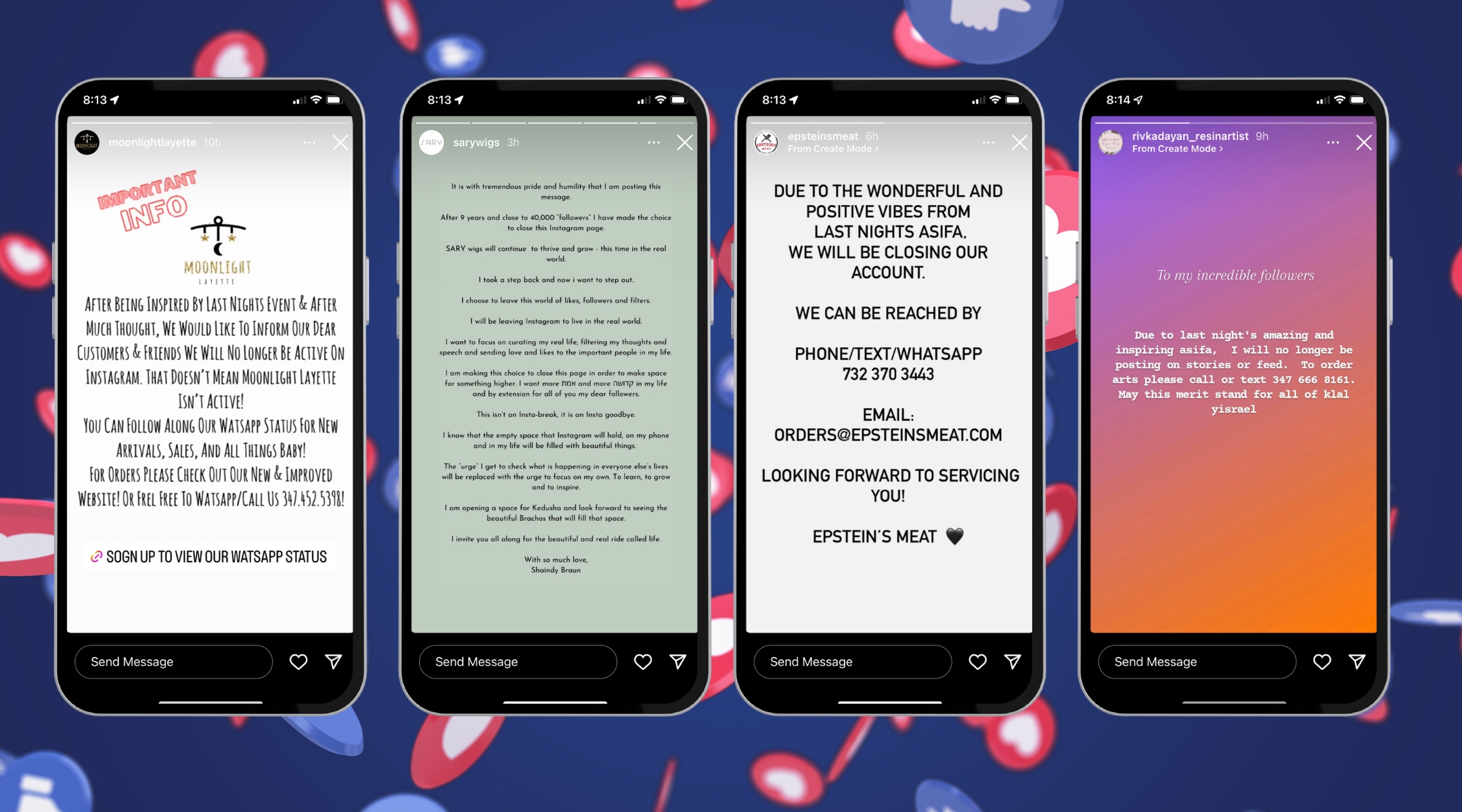

Screenshots from Orthodox Instagram accounts that announced they would be shutting down after the anti-social media rally in New Jersey. (Design by Jackie Hajdenberg)

(JTA) — Shaindy Braun and her wig business had nearly 40,000 followers on Instagram, amassed over nine years, when she abruptly announced her departure from the social media platform.

“I choose to leave this world of likes, followers and filters,” Braun wrote last week. “I will be leaving Instagram to live in the real world. I want to focus on curating my real life, filtering my thoughts and speech and sending love and likes to the important people in my life.”

Then she deleted her profile, cutting off a major line of communication to clients — and potential buyers — of Sary Wigs, a Lakewood-based company providing human-hair wigs to Orthodox Jewish women in New Jersey and beyond.

She wasn’t the only one: Moonlight Layette, a baby clothing brand, announced it would stop engaging actively on Instagram, directing customers to a WhatsApp number instead. So did Rivka Dayan, a resin artist who makes Judaica products, and others.

Their decisions might have come as a surprise to the brands’ followers — except that many of them had also tuned into two massive gatherings in Newark last week exhorting Orthodox Jewish women to put away their phones and disconnect from social networks.

Coming a decade after a landmark rally aimed at warning Orthodox men about the dangers of the internet, the rallies were meant to inspire women to spend more time away from their cell phones, according to its organizers. But critics in the Hasidic Orthodox community, including women who attended or listened in via a special phone line for remote participation, said pressure to attend was intense — and that the message was far from uplifting.

“They force themselves to sit through this, being told how evil they are, how decadent they are today with their obsessions with ridiculous things and how spiritually inferior they are,” one Hasidic woman told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency on the condition of anonymity because she still lives in a Hasidic community in Borough Park. “And they sit there and they listen to it and they nod and they accept it all and they internalize it.”

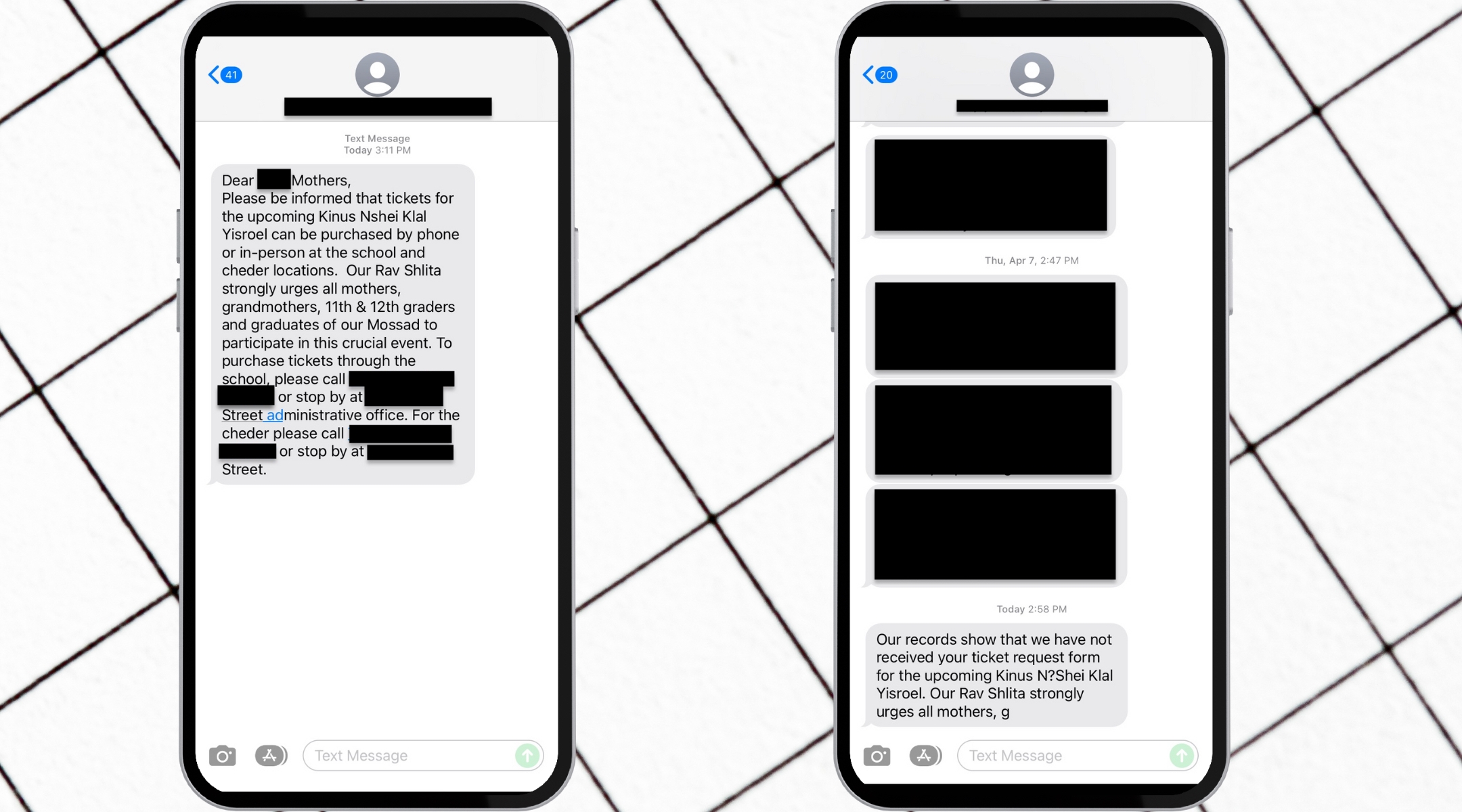

Known as an asifa or kinus (Hebrew words for gathering), the rallies drew tens of thousands of Hasidic Orthodox women to the Prudential Center in Newark last week, many transported on charter buses from Orthodox areas such as Lakewood, New Jersey, and Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Women with children in the Bais Yaakov network of schools received text messages and letters saying that the school rabbis urged them to attend; one mother told JTA that she was told her children would be expelled if she did not attend the rally, where tickets cost $54.

Text messages to the mothers of students in Hasidic schools repeatedly encouraged them to attend the anti-technology rally. (Design by Jackie Hajdenberg)

One rally was in English, while the other was in Yiddish, the dominant language spoken in many of New York’s Hasidic communities. The events, widely referred to as “nekadesh rallies” using the Hebrew word meaning “make holy,” appealed to women’s maternal instincts — a winning line in a community where fertility is prized and women typically have many children and are responsible for their education.

“I miss the great times that we used to have before you got the cell phone that your boss gave you,” a young boy said during a speech at the Yiddish rally, according to a recording of the event. “I miss your sweet smile. Do you remember our conversations, when we used to laugh at our own stories, and not because we were listening to silly jokes on the little black box?”

At the English-language rally, half of the speakers were women, and at one point, the male rabbis who spoke left the arena so the women could sing together. The speakers presented the issue of social media as one where Orthodox women can choose more or less pious ways to engage with the internet. Among the speakers was Rina Tarshish, a rebbetzin and the director of a women’s seminary in Israel who is widely respected in the Hasidic world.

The rally was intense at times, with attendees being told at one point that technology is a manifestation of Satan’s efforts to spread rot in the world, according to a Twitter thread by someone who transcribed much of the event. But the Yiddish-language rally was more strident in tone and tackled women’s participation in civic life offline as well, according to people who were present. One rabbi who spoke even instructed women not to speak on the street, except in cases of emergency.

The event came 10 years after 40,000 Orthodox men were similarly exhorted to give up their smartphones at a major anti-internet asifa at Citi Field in New York City. Then, the message was about insulating the community from outside influences.

Some 40,000 Haredi Orthodox men filled Citi Field in New York to rally against the dangers of the Internet, May 20, 2012. (Ben Sales)

Ayala Fader, an anthropology professor at Fordham University who studies Hasidic communities, said what happened next helps explain the latest rallies.

“Men were refusing to give up their smartphones,” she said. “So leadership decided to focus on women and their responsibility for rearing kids and keeping the home and really protecting the next generation.”

Many Orthodox women who have found homes on social media built connections within their own extended communities. Instagram in particular has been both a tool for building businesses in a community where working outside the home can be discouraged and logistically challenging. Orthodox women have also used social media for activism, such as to share experiences with infertility, combat racism and fight antisemitism. Some, seeking to comply with expectations around modesty, have even operated women-only accounts.

Hearing that they should set all of that aside struck some women who were invited to the rally as offensive. Compounding their frustration was the fact that attendees were prohibited from bringing cell phones, taking pictures and sharing the event on social media, and Orthodox media covered the rallies without printing pictures of the women who attended.

“Women finally found an outlet where they can network and it lets you build successful businesses via the internet,” said one Hasidic woman who works in digital marketing and is the sole breadwinner for her family. “And now the men realize, ‘hey, this is terrible! Women having access to other women that are talented, successful, powerful businesswomen. So let’s condense them even more, make them into mere shadows.’”

The rallies were organized by the Technology Awareness Group, or TAG, a nonprofit founded in 2011, shortly before the men’s rally, with a mission of helping Jewish internet users avoid pornography and other harmful influences online. Shmuli Rosenberg, a marketing executive who promoted the event as well as many others targeting Orthodox Jews, said the goal was not to ask women to eschew the Internet or having a public profile.

“It’s far from cutting people off,” he said. “It’s helping people find, in their own life, what will allow them to be more connected to their families and their children and themselves and feel uplifted and elevated and happy.”

Rosenberg said the rallies were limited to women only because the organizers wanted to offer some programming, including women’s singing, that would not be possible under communal norms in a mixed-gender setting.

“This wasn’t specifically targeting women versus men,” he said. “This was targeting everyone. And in our communities, it would be totally unacceptable to say that men can access the internet or information more than women.”

Some women who attended, like Braun, the wigmaker, found the events inspiring.

“I know, it’s kinda contradictory to talk about it here, online,” one woman wrote on the Orthodox women’s forum ImaMother. “But those who were there, in a positive mind, understood that it wasn’t about all or nothing.”

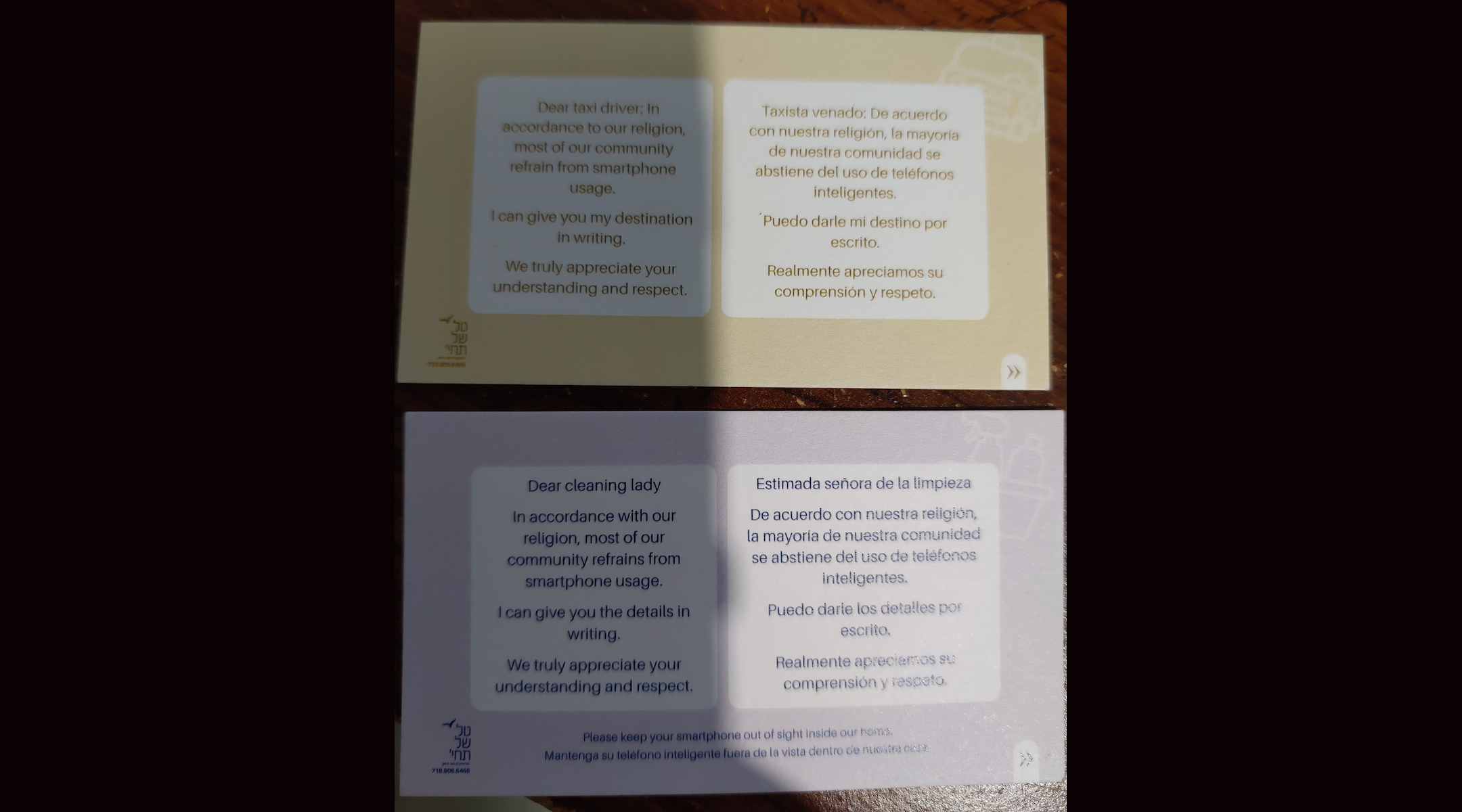

But others said they saw in the events a dangerous tendency in Orthodox communities to set rules far beyond what is required by Jewish law. On their way out of the rallies, women were handed cards that they could give to their taxi drivers and housekeepers to explain why they cannot touch smartphones to type in their address and to ask that smartphones not be used in their homes.

“Dear cleaning lady,” one of the cards read, “In accordance with our religion, most of our community refrains from smartphone usage. I can give you the details in writing. Please keep your smartphone out of sight inside our home.”

Women were handed cards to be given to their taxi drivers and maids that explained why they cannot use or be near smartphones. (Courtesy photo from an unnamed source)

Nothing in Jewish law, known as halacha, prohibits a woman from typing in her address on a phone or creates any obligation for non-Jews. But Rayne Lunger, a woman who grew up Hasidic and is now active on social media, said she was familiar with the impulse to observe more than the letter of the law.

She likened the call for women not to use smartphones to what has happened with expectations around skirt length. In the past, women were considered modest if their skirts covered their knees, she said, but over time, 4 inches below the knee became the norm, and now women can face criticism if their skirts do not reach at least 6 inches below the knee.

“People want to be good and do the right thing,” Lunger said. “And they’re sometimes building stringencies on top of stringencies on top of stringencies that make no sense because they have no reference point.”

Not all Hasidic Jews are wrestling with the issue of internet use in the same way. The Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic movement, for example, has embraced new technologies and uses social media in its outreach, and was not involved in any of these events.

But for women who do choose to roll back their internet usage, groups such as TAG stand ready to install “kosher” filters on their phones and computers.

“The ultra-Orthodox mostly think that the medium is fine wherever you use it in the clean way, or kosher way,” said Rivka Neriya-Ben Shahar, a professor at Sapir Academic College in Israel who studies haredi Orthodox approaches to media. “They feel very safe once they can control the content.”

Like parental controls on an iPad or television, kosher filters typically block access to websites or content that is considered inappropriate in the community, such as pornography, gambling sites, or anything related to violence or drugs. They also may block secular content and, separately, can sometimes be glitchy and block content that is not actually out of bounds in the Hasidic world, including health and safety information that women need.

Exactly how many women will install filters, cede their cell phones or cut communications with their customers as a result of the recent gatherings remains to be seen. But what’s clear is that the press to get New York-area Orthodox women to reconsider their internet use continues, even as the latest events themselves fade into the past.

Women are still closing their accounts, according to participants on Orthodox Instagram, and now another event has been scheduled: A replay of the asifa is set for Tuesday at Tiferes Bais Yaakov School in Lakewood. The school’s ballroom can accommodate 4,600, according to a Jewish event planning website, and tickets are $20.

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.