How a Jewish legislator’s vote legalized abortion in New York in 1970

George Michaels couldn’t face his family on Passover if the bill failed. His last-minute ‘yes’ was the deciding vote.

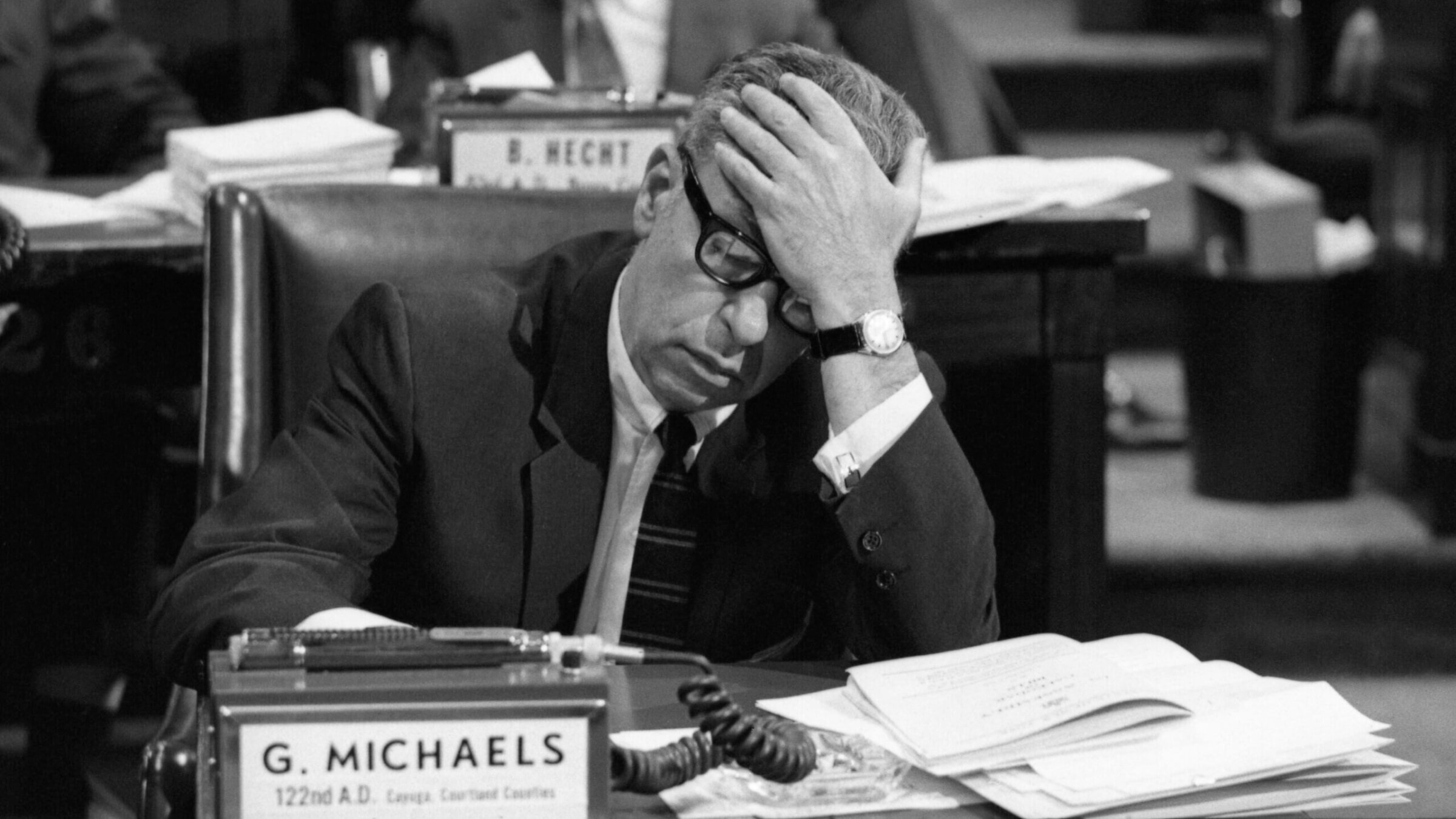

New York State Assemblyman George Michaels holds his head after changing his vote to “yes” on what was at the time the most liberal abortion law in the U.S. Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

George M. Michaels was a Jewish legislator representing a heavily Catholic district in New York when efforts to legalize abortion in the state came to a head in April 1970. Priests and nuns paced the chamber floor; Michaels’ daughter-in-law and one of his sons, who was in rabbinical school, urged him to vote yes.

With tears in his eyes, knowing he would lose Democratic Party support for the next election, Michaels cast the deciding “yes” vote.

“If I am ever going to have peace in my family … I cannot go back to [them] on the first night of Passover and tell them that George Michaels defeated this bill,” he told the stunned chamber.

More than 50 years later, Michaels’ son, the rabbi, and his granddaughters reflected on his legacy and the ramifications of that fateful vote. The story of how the vote came about is even more compelling in light of the end of Roe v. Wade and New York Gov. Kathy Hochul pledging to preserve abortion rights as states across the country race to end or restrict them.

At first, bowing to political pressure

Born and raised in New York City, the son of Polish immigrants who were secular Jews, Michaels moved to Auburn, New York, a small city in the Finger Lakes region, after marrying his college sweetheart. He had served in the New York State Assembly for 10 years by 1970 when a bill to legalize abortion up to 24 weeks of pregnancy came up for a vote.

A more liberal version of the bill, without the 24-week limit, passed 31-26 in the state Senate on March 18 with bipartisan support. The Assembly took up the amended bill on March 30, but it failed to pass. Michaels voted against it at the request of Cayuga County Democratic officials, even though he personally supported giving women the right to choose.

The bill’s primary sponsor, Republican Constance E. Cook, maneuvered another vote on the bill on April 9 using a parliamentary procedure. The Catholic Church had ramped up opposition after being caught off guard by Senate approval in March. During hours of contentious, emotional debate, legislators spoke about their personal convictions and the pressures they faced from constituents and the church. A few members switched their votes. The bill needed 76 votes to pass and was about to go down in defeat, with an even 74 votes for it and 74 against it.

‘I must keep peace in my family’

Michaels was initially among those voting against the measure, but as the roll call was ending, he asked to change his vote. “I fully appreciate that this is the termination of my career,” he said, pale and fighting back tears as TV cameras turned to him.

The New York Times reported that he sobbed as he told the chamber about the tension in his family, including his son, a student at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati, begging him not to be the one who defeated the bill. “I must keep peace in my family,” he said.

That son, Rabbi James Michaels, now a retired chaplain, remembers asking his dad a week before the abortion vote what he planned to do. His dad said he had to vote against the legislation. “I understand,” the rabbi recalled telling his father, “as long as your vote isn’t the one that defeats the bill.”

George Michaels’ daughter-in-law Sarah, who was married to his other son Lee at the time, was even more persuasive, according to family members. A college friend of Sarah’s had nearly died from an illegal abortion, and as a social worker, she saw how difficult it was for single mothers to raise children they hadn’t planned to have. Sarah asked her father-in-law how the vote would go, and he assured her that the abortion bill would pass that year or the next. As James Michaels recalled, she then asked him, “How many more women are going to die or be mutilated because of our dumb old legislature?”

The arrival of George Michaels’ first granddaughter two years before the vote also weighed heavily on him, he told family members years after the fateful vote. His granddaughter Dania Schulman remembers him saying that he didn’t want any of his granddaughters or future great-granddaughters forced into a back-alley abortion to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. “That is why he made that decision,” Schulman said.

The end of a political career

Ten days after the vote, on April 19, members of the Cayuga County Democratic Committee withdrew their endorsement of Michaels. He lost the Democratic primary in June.

Friends whom he and his wife had known for decades turned on them. His law firm of 40 years disbanded. He went into practice with his son Lee.

“I remember hearing stories about my grandmother and grandfather receiving really horrible hate mail,” Michaels’ oldest granddaughter, Becca Kornet, said. “They had a police detail around the house to make sure people were safe.”

Eventually, though, things turned around. Former clients returned. “His life wasn’t over,” granddaughter Anna Michaels-Boffy said. “People did think of him as a brave person.” The hate mail lasted for weeks, but the letters of praise and thanks continued for the rest of his life.

In 1971, the New York Society for Ethical Culture gave Michaels its Humanitarian Award. In accepting the honor, he refuted “the myth that I made a great personal sacrifice,” the Times reported. “I realize that I was given an opportunity that few men in or out of public life ever attain — the opportunity to shape events rather than merely react to them,” he said.

The next year the Assembly voted to repeal the abortion law, but Gov. Nelson Rockefeller vetoed the bill. In 1973, with Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court protected the right to abortion before 24 weeks.

‘The legislator who changed abortion law’

The story of George Michaels’ abortion vote looms large in his family. “I don’t remember when someone told me for the first time,” said Kornet. “It was always part of everything. I mean, it’s impacted me in so many ways. For one, I’m very politically active and very active in social justice initiatives, and abortion rights are at the top.”

When Michaels died in 1992, at age 82, the Times, in its obituary, called him the “legislator who changed abortion law.” He is survived by 23 grandchildren and great-grandchildren, many of whom, Schulman said, “are so fiercely passionate about women’s rights.”

Because of Michaels and other legislators and activists, New York became and continues to be a haven for women seeking safe, legal abortions. He upheld abortion rights in defiance of a powerful church, and he chose inner peace and progressive change over politics. A tribute to him on display at New York’s Equal Rights Heritage Center in Auburn says Michaels “made history” with his vote, and asks: “What is the use of getting elected or reelected if you don’t stand for something?”