Born and raised Jewish, the man leading 19 years of protests against a Michigan synagogue embraces antisemitic tropes

Henry Herskovitz denies the Holocaust and believes that antisemitism is rooted in ‘bad Jewish behavior’

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

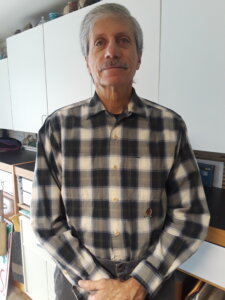

The 76-year-old Holocaust denier who has protested outside a Michigan synagogue nearly every Shabbat for 19 years was born Jewish, attended Hebrew school, had a bar mitzvah and used to attend High Holiday services at the synagogue he targets.

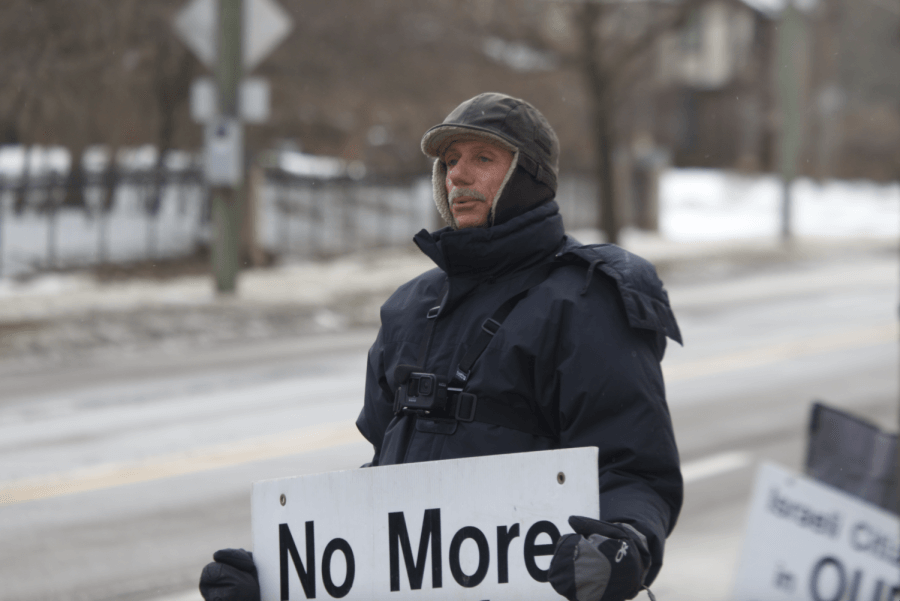

What began as a protest against Israeli policies has morphed into one that challenges the Jewish state’s right to exist and traffics in blatantly antisemitic tropes. The organizer, Henry Herskovitz, holds signs with slogans like “Resist Jewish Power,” “No More Holocaust Movies” and “End Jewish Supremacism in Palestine,” along with one honoring a man who loved Hitler.

Unsuccessful lawsuits

The weekly vigil outside an Ann Arbor synagogue building attracted national attention after two congregants sued, accusing the protesters of violating their right to freely exercise their religion. The lawsuits failed. Federal judges ruled that the Constitution protects the protesters’ free speech, and ordered the congregants to pay $159,000 in legal fees. The U.S. Supreme Court this spring refused to hear appeals.

But little has been written about the man spearheading the ongoing Shabbat demonstrations. In an interview, Herskovitz said that visits to Iraq, Israel and the West Bank led him not only to abandon Judaism but to believe baseless conspiracy theories implicating Israel for the 9/11 terror attacks and to reject the historical record of the Holocaust.

Herskovitz, in short, blames Jews for antisemitism. “I’m convinced that anti-Jewish sentiment always follows bad Jewish behavior,” he said.

When Herskovitz started protesting at the Ann Arbor synagogue nearly two decades ago, his group was called “Jewish Witnesses for Peace and Friends.” He said there were as many as 13 Jewish regulars. He said the others have since died. Most weeks, the group Herskovitz now calls “Witness for Peace” includes just himself and a couple of others gathering in front of the synagogue. He has also picketed outside a local Holocaust museum and Jewish Federation office.

Turning points

Herskovitz said he grew up in the Turtle Creek section of Pittsburgh before moving to the heavily Jewish Squirrel Hill neighborhood, site of the 2018 Tree of Life massacre that killed 11 Jews during Shabbat services.

“My mother wanted my sister to marry a Jew and Turtle Creek had very few Jews,” he recalled. “My family and my aunt and her family were the only Jews there.” He was bar mitzvahed at Congregation Beth Shalom, a Conservative shul in Squirrel Hill, in 1959.

Herskovitz, who worked as a mechanical engineer for a compressor manufacturer in Michigan before retiring in 2019, cited two experiences that caused him to question what he was brought up to believe about Israel and Jews.

The first was in 2000, when he and a friend decided to fly to Iraq to “take a little tour” to observe the effects of the sanctions that had been imposed by the United Nations Security Council following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. There, he said, they visited a hospital where families who couldn’t afford a nurse were tending to their own children. He saw a father sitting on the bed of his son, a cancer patient.

“The man looked like a terrorist with a dark beard, but then I noticed that he was crying. Then I started crying,” Herzkovitz recalled. “I had been told by the press that these were terrorist people, and I found out that this person was a real human being. It struck me very hard.”

After returning to Michigan, he made a sign that read, “End the Sanctions on Iraq” and held it aloft on an Ann Arbor street corner.

Impact of 9/11

But Herskovitz said 9/11 had an even greater impact on his thinking. He bought into the false claims that Israel had something to do with the Sept. 11th attacks on the World Trade Center and other U.S. targets. And he continued to question what he had been taught about the country. “I asked, ‘What else have I been wrong about?’” he recalled.

Now, Herskovitz said, he believes Israel has no right to exist and that the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean belongs to Palestinians, not Jews. He traveled to Tel Aviv in 2002, and said that aboard the plane, a rabbi told him that Palestinians teach their children to hate Jews.

After landing, he said, he went to the West Bank and asked a Palestinian teacher if what the rabbi said was true.

“You can’t teach people to hate, you have to show them,” he recalled her saying. She talked about how Palestinian are made to wait for hours at Israeli military checkpoints in the West Bank, and are often humiliated in front of their children by the soldiers. Herskovitz said her conclusion made sense to him, and he came away agreeing that, as he put it, “hatred is earned, not taught.”

A familiar place to protest

There are three synagogues in Ann Arbor. Herkovitz said he chose to demonstrate every Shabbat outside a building that houses both the Conservative Beth Israel Congregation (as well as another congregation) because he had attended Yom Kippur services there.

“I went there for 15 years and followed the fasting,” he recalled, admitting that he sometimes bought a ticket and sometimes snuck in. “I probably stopped going shortly after the vigil began in 2003.”

Now, Herskovitz said, “I’m out of the faith. It doesn’t appeal to me.”

Instead, Herskovitz said, “I call myself a fledgling Christian and I go to church on Christmas Eve.” On one occasion, he recalled delighting in a live creche in which Joseph was talking on a cellphone. “I thought that was pretty hilarious,” he said.

He could not really explain why the protests have persisted for so many years. He said he initially hoped to change congregants’ minds about their support for Israel. Now, he sees his audience as the entire community.

Supporting a Holocaust denier

His supporters have also protested when Israeli groups or speakers come to town or when the local Jewish federation holds its events. On Holocaust Remembrance Day in 2014, they picketed a Holocaust museum with signs saying “Free Ernst Zundel,” author of a book titled “The Hitler We Knew and Loved,” who was jailed in Germany for Holocaust denial and inciting racial hatred. He said he visited Zundel in prison and that his sister was “aghast that I visited him.” (Zundel died in 2017.)

In January, the Ann Arbor City Council for the first time condemned the protests.

Herskovitz said his parents died before he started the protests and that he doesn’t speak with his sister about them.

Asked about the sign decrying Holocaust movies, Herskovitz said: “We’re sick of the movies — the Jews crying out in pain.” Films about the Holocaust, including director Ken Burns’ upcoming documentary for PBS, are a way for Hollywood to manufacture sympathy for Jews, he added.

Herskovitz said he has never spoken with a Holocaust survivor, but has visited Auschwitz and Dachau. Still, he rejects the historical record, and has convinced himself that there were no gas chambers at these or other concentration camps. He said that Hitler never ordered the mass extermination of the Jews of Europe, and that crematoria were only used to dispose of bodies of people that succumbed to overwork, “malnutrition” or disease. The Anti-Defamation League has labeled Herskovitz a Holocaust denier.