Mark Spitz made Olympic history in 1972. Here’s why his Jewish identity mattered in Munich

He won 7 gold medals for swimming. A day after his final race, the Munich massacre unfolded

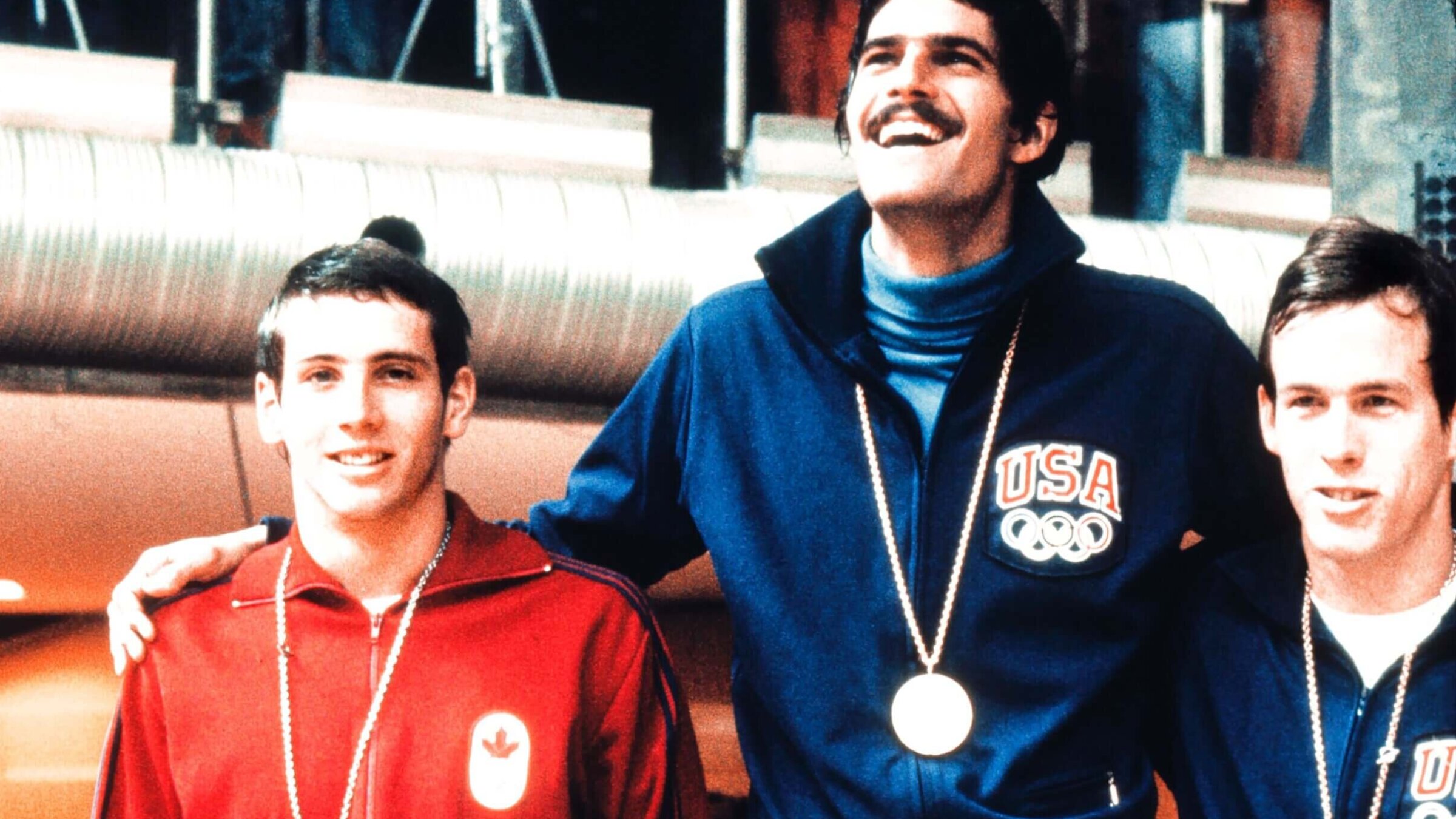

Mark Spitz, center, smiles on the podium after winning the gold medal in the 100-meter butterfly ahead of Bruce Robertson, left, and Jerry Heindenreich, right, Aug. 31, 1972, at the Olympic Games in Munich. Photo by AFP via Getty Images

Fifty years ago, on Sept. 5, 1972, a horrific story unfolded in Munich, Germany. Palestinian terrorists had murdered two Israelis at the Olympic Games and taken nine more hostage. Within hours, those hostages were dead as well.

But the day before the massacre, a different story was making headlines out of Munich — a story of triumph. American swimmer Mark Spitz had made history by winning seven gold medals over the course of one Olympics, and he’d set world records with every win. The feat stood unsurpassed for 36 years, when another American swimmer, Michael Phelps, set his own records at the Beijing Olympics.

It’s only right, as we look back on the 1972 Games, that the massacre and the aftermath of the tragedy take center stage. The victims’ families continue to cope with grief and trauma. Both Germany and Israel will be marking the solemn anniversary with ceremonies.

But Spitz’s incredible accomplishments deserve recognition as well. He’s not only one of the greatest Jewish athletes in history — right up there with Sandy Koufax — but he’s also one of the greatest athletes, period. (Sports Illustrated ranked him No. 33 on a list of the 100 top athletes of the 20th century.)

Here’s a look at Spitz’s life and career, along with why his Jewish identity mattered at the Munich Games.

Competing young, and winning

By age 10, Spitz was already a standout swimmer and getting private swim lessons near his family’s home in Sacramento, California. The Spitzes eventually moved to Santa Clara so he could be mentored by Olympic swim coach George Haines.

At age 14, he was competing in national championships, and by 17, he had already set or tied five U.S. records and broken five world records.

His drive to win was instilled by his father, Arnold, who famously told him: “Swimming isn’t everything. Winning is.”

At the ’68 Olympics, Spitz made a cocksure prediction that he’d win six golds. But he only won two, and both were for team relays, not individual races. He was roundly shamed by the media for his arrogance, and later said it was the “worst moment” in his life.

Still, those two golds from Mexico put him in rare company among Olympians. He’s one of just five athletes in history to have won a total of nine or more golds from multiple Olympic Games.

Jewish identity

Not much has been written about whether Spitz’s family was particularly observant, but one often-repeated story makes his father’s priorities clear.

When he was 10 and his hours in the pool began to interfere with Hebrew school, his father supposedly told the rabbi: “Even God likes a winner.”

And when his first coach, Sherman Chavoor, invited him to swim at a private club called Arden Hills, in an era when many clubs excluded Jews, African Americans and other people of color, Spitz’s dad was concerned.

“Can you take this kid on? Are you going to be prejudiced?” Chavoor’s daughter, Shelley, recalled Arnold Spitz asking her father. Her dad responded: “He swims! I don’t care!”

She said in an interview that her dad, who was Portuguese, had experienced discrimination himself, and “was pretty sensitive to some of the things Mark dealt with in terms of antisemitism.”

Spitz’s first international competition was at the 1965 Maccabiah Games in Israel. He returned to Israel for the ’69 Maccabiahs after his disappointing performance at the Olympics in Mexico.

The Munich Games took place just 27 years after the end of World War II. Any hopes the Germans had that hosting the games might soften their image were shattered, of course, by the massacre, which included a bungled rescue operation that led to the hostages’ deaths.

But before the attacks unfolded, Spitz was asked how he felt, as a Jewish athlete, competing on German soil. “I have no qualms about Germany at all,” he said shortly after arriving. “Maybe I should, but I wasn’t even born when all that stuff happened.”

Asked again about being in Germany after he’d won his medals, but before the attacks, he gestured at a lampshade and offered this unsettling response: “Actually, I’ve always liked this country, even though this shade is probably made out of one of my aunts.”

Whisked away

In an interview with The New York Times a decade after the ’72 Olympics, Spitz said he only learned of the attack and the ongoing hostage situation at a press conference where he thought he’d be talking about swimming.

”I was shocked and stunned,” he told the Times. “The press wanted my words because, first, I was Jewish, and second, they thought I was some kind of spokesman for athletes.”

As the Times put it: “He was prepared neither to be a spokesman nor, later, to discuss authoritatively the political ramifications of the murder of 11 Israeli athletes and officials.”

Spitz had planned to leave Munich after his competitions were over, even though the games were scheduled to continue for another week. But now officials feared that being Jewish might make him a target. He was given a police and military guard and immediately flew to London. “Frankly,” he told the Times, “I was scared.”

Asked about the attacks as he arrived at Heathrow Airport, he said simply: “I think they’re tragic.”

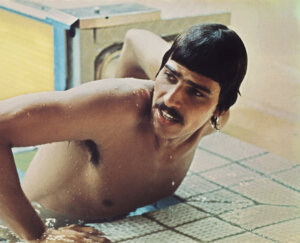

That famous mustache

Look at any photo of Spitz from Munich and you can’t help but be struck by the difference between his appearance then, and how swimmers compete today. He had no goggles and no swim cap. In fact, he had a full head of dark hair and a mustache. Considering that nowadays even male swimmers routinely shave their body hair to reduce resistance in the water, it was a bold look.

The mustache in particular made him stand out even before he’d won any medals. He’d planned to shave it off, but so many people were talking about it that he decided not to. In fact, when asked in Munich if the facial hair would slow him down, he claimed, in his typically brash way, that it would actually help him go faster by deflecting water away from his mouth.

After Munich

Spitz was 22 coming out of Munich. He had a bachelor’s degree from Indiana University, and in interviews at the games, he said he planned to immediately retire from competitive swimming and go to dental school. After winning his fourth race in Munich, when asked what he’d do with all his medals, he said: “Maybe I’ll hang ’em in my dental office.”

Things changed when he got home. Suddenly, Mark Spitz was everywhere: magazine covers, TV shows and on 300,000 posters, priced at $2 apiece, wearing his red, white and blue swimsuit, medals in hand. “Maybe I’ll do some nudie movies,” he said at one point. “I’m hot to trot.”

Repped by the William Morris Agency in an era when athletes did not walk out of wins and into sneaker commercials, Spitz was criticized for commercializing his fame. He was a spokesperson for Schick razors and appeared on billboards promoting milk for the Milk Advisory Committee. His deal with Schick gave him use of a $65,000 yacht. And when he was asked about that dental school dream, he reportedly replied, “Are you kidding?” In later years, he reflected that he had been unprepared for the maelstrom he was thrust into, and that it took him a long time to go back to living a normal life.

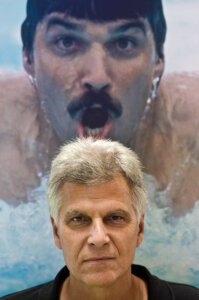

Spitz looks back

Today, at age 72, the mustache is gone. He’s been married to the same woman, Suzy Weiner, since 1973. He’s described on his website as not just the “world’s greatest swimmer,” but also an “athlete, motivational speaker, influencer, investor, husband, father.”

Spitz did not respond to requests for comment for this story made through his website, his social media accounts or USA Swimming, the official organization for swimmers representing the U.S. But in a one-hour documentary released a few weeks before the 50th anniversary, Spitz seemed introspective and even somewhat humble looking back. “I believe the greatness of an athlete is not to recognize what you did right but to recognize what you did wrong,” he says in the film.

He recalled his father cautioning him, after Munich, against letting it all go to his head: “You’re still like everybody else. You’ve got to put your pants on one leg at a time.”

Spitz added: “I was just an ordinary guy that trained hard, diligently, and on one particular week, did extraordinary things.”