Yahrzeit plaques and other mementos collected, as Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life prepares for future

Ninety-minute window on March 19 afforded community chance to retrieve items, pay respects, before building transitions

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

This article originally appeared on the Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle, and was reprinted here with permission.

When the doors to Tree of Life Congregation’s building briefly opened on March 19, Stephanie Davis didn’t know what to expect. More than 1,600 days had passed since she last entered the synagogue.

Davis wanted to return to the building after the Oct. 27, 2018, attack. Tree of Life was where she attended Hebrew school, where her brother became a bar mitzvah, where her sister celebrated her wedding and where Davis taught music on Sundays. Her father, Morris Sedaka, memorialized his own parents, Victor and Sophie Sedaka, by donating in their names. For generations, Davis’ family ties were bolted to the walls for passersby to remember.

On Sunday, she entered the building to retrieve those plaques.

Just three days earlier, she saw a message on Facebook announcing a 90-minute window for people to “pick up yahrzeit plaques, art and other remaining items.”

Between 10:30 a.m. and noon, Davis and about 20 others — many of whom were congregational leaders — searched the social hall.

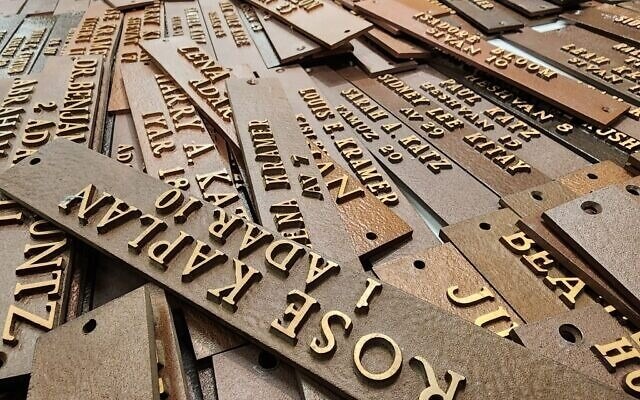

Inside the expansive room were tables holding hundreds of yahrzeit plaques, but they were a mere fraction of the items collected. Assembled within the social hall were photos, books, discarded prayer shawls, old Torah covers, cassettes, VHS tapes, T-shirts, a bowling trophy, paintings, posters, bags of garbage, bookcases, menorahs, ceiling tiles, tools and furniture. There were rows of stacked chairs, vacuums, lecterns, filing cabinets, refrigerators and a vintage couch whose pink, brown and off-white hues recalled an era when synagogues had youth lounges and the youth lounges hosted flocks of children and teens.

Alan Hausman, Tree of Life’s president, said the congregation is doing its best to ensure salvageable items avoid a landfill.

Some furniture went to nearby synagogues, churches and nonprofits. Dishes and glassware are going to immigrant families. Rabbi Jeffrey Myers and his wife, Janice Myers, spent more than two hours on Sunday searching stacks for things area children might enjoy.

“We want to do as much good as we can,” Hausman said.

Among the piles inside Tree of Life’s social hall were items that will soon return to the earth. Discarded pairs of tefillin, old prayer books and printed copies of the Bible, “anything of a holy nature,” will get boxed and buried, as is Jewish custom, Rabbi Myers said.

For several people who entered the building, the day was a transitional point in Tree of Life’s history.

The congregation was chartered in 1865, according to the Rauh Jewish Archives. It was housed first in downtown Pittsburgh, then Oakland, and moved to Squirrel Hill in 1946. For nearly 72 years, generations worshipped, learned and socialized inside the building on Shady and Wilkins avenues.

“I remember it from being a child,” Diane Heller Klein said. “I was bat mitzvahed here. I was confirmed here. I went to Sunday school and Hebrew school here. My mother was president of the Sisterhood five times. My grandmother was president of the Sisterhood five times. My grandma and grandpa were both life trustees. I mean, our family roots are really deep.”

Klein learned about the building’s opening a day earlier from her sister, who lives in Florida and happened to see the Facebook post.

Sunday morning Klein drove 40 minutes from her home in Plum Borough to Squirrel Hill. She was looking for a picture of her great-grandfather, Abraham. A Goldstein, the man who Tree of Life named its Hebrew school after.

According to a family history, written by Klein’s grandmother Mildred Gould Reichman, Goldstein came to Pittsburgh to teach at Tree of Life in 1884, shortly after the congregation bought a building on the corner of Fourth Avenue and Ross Street in downtown Pittsburgh. He and his wife, Anna, lived in the building, where she gave birth to five children, including Reichman.

Goldstein was revered. After he died in 1938, Tree of Life’s Rabbi Herman Hailperin memorialized him by writing, “We often say that a man creates his own position in life. This is so true of the late Abraham A. Goldstein, sexton and Hebrew teacher of the Tree of Life for more than fifty years…. No rabbi was ever respected by his congregation any more than was the late Mr. Goldstein. He demands the request because of his learning, his sincerity, and his life-long devotion to the Tree of Life congregation.”

Klein knew there was a photo of her great-grandfather inside the building. She scoured the social hall but couldn’t find it. She asked Myers if he had any idea where she could find it.

“He knew exactly where it was,” Klein said.

She held the framed photograph and adjacent proclamation heralding her great-grandfather’s half-century of service to Tree of Life. Then she began to cry.

After Oct. 27, 2018, “I had been back on the outside, to just pay respects, but this was the first time I’ve been inside,” Klein said. “And it’s difficult because I remember it. So it’s just been kind of an emotional thing walking through here and going, ‘Oh God, oh my God, I can’t believe what happened here, that son of a bitch,’ and just really unkind words and thoughts towards that gentleman.”

Linda Schugar leafed through photographs on a table inside the social hall. She pointed to pictures of fellow minyan-goers, some who died during the massacre, some who died in the years since.

Next to the stacks of photos were plates, bowls and cups.

“I remember all the dishes,” she said. “We used these for daily minyans.”

Schugar returned to the photos, found several of her with former congregants and placed the images inside a large, black plastic bag.

“We loved what we did,” she said.

As individuals searched the piles for tangible reminders of family, friends and congregational life, Hausman continued boxing materials.

“We don’t take any of this lightly,” he said. “We have been doing a lot of consultation with different people and doing what’s appropriate for this site.”

Significant portions of Tree of Life are slated for razing and rebuilding. According to architect Daniel Libeskind’s renderings, a 45,000-square-foot complex will house Tree of Life, a new nonprofit dedicated to ending antisemitism, and the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh.

The congregation has existed for nearly 160 years. Placing every nameplate, seat plate, yahrzeit marker and engraved remembrance on the building’s new walls is impossible, Myers said.

“You can’t just create one memorial board and fix all the plaques because they’re all different lengths, widths, depths and thicknesses,” he explained. “The respectful and kind thing to do is to return plaques to descendants until we finalize the plans for how we are going to remember the rich history of Tree of Life.”

After probing hundreds of metal plates, Davis finally found the two she was looking for. She pressed the thin pieces, bearing Victor and Sophie Sedaka’s names, together.

“I’m named for my grandmother, and my brother is named for my grandfather,” she said. “Holding those plaques with their names on it, in my hand, is so emotional.”

While locating those memorials, Davis ran her fingers across the names of “so many people” she knew. She didn’t know whether to take those plaques or leave them. She asked what would become of those that nobody retrieved.

“We will still store them and continue to make them available,” Myers said.

A March 20 Facebook post from Tree of Life announced three additional days and times when people could pick up “yahrzeit plaques and other items, including furniture, dishes and books.”

Hours after Davis left the building, she remained unsettled.

Others — like Jeremy Goldman, who came to retrieve his grandparents’ seat plates — described the experience as “cathartic.”

Davis didn’t feel the same.

She said that after the massacre, she reached out to congregational leadership and asked whether she could enter the building to mourn those who were killed and to see the spaces her family had cherished for generations. She said her request was denied.

Once, while walking down Wilkins Avenue on a Saturday, Davis noticed the gate was open.

“People were coming out, and I felt myself wanting to stop them and ask what was going on inside, what they were doing,” she said.

But she didn’t ask.

When the doors to Tree of Life briefly opened on March 19, she was the first one waiting outside.

The building was shuttered for so long that it became “the secret behind the gates,” she said. “No one was allowed in, but now it’s open and it’s almost anticlimactic. There could have been a more appropriate way for us to pay our respects, to offer support to people.”

Davis paused before continuing.

“I have so much emotion in me right now. It’s so hard to verbalize. We haven’t forgotten the people who were there before us, or the people who were there when it happened. Don’t forget them just because the building won’t be there. I know I won’t forget, that’s for sure.”