Amid a rabbi shortage, some synagogues opt for a cantor instead

More cantors are taking on rabbinical roles, and some are seeking out dual ordination

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Faced with a dearth of rabbis, a small but increasing number of synagogues are relying on cantors as their sole spiritual leaders.

Cantor Jeremy Lipton, who directs job placement services for the Cantors Assembly, a professional organization affiliated with the Conservative movement, counted 24 cantors currently serving as one of its congregation’s sole spiritual leaders. That compares to about 10 a decade ago.

Many synagogue leaders have grown frustrated in their search for a rabbi and turned to the Assembly, Lipton said. “Because of the shortage of rabbinic candidates, congregations are expanding beyond looking only for rabbis and have had to reimagine what they want.”

A similar story is unfolding in the Reform movement, the largest stream of American Judaism. Today, 13 cantors are currently serving as the only spiritual leaders of a Reform congregation, according to Cantor Jill Abramson, interim director of the sacred music school within the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion.

Cantor Kay Greenwald, who has served for 11 years as director of placement for the Reform movement’s American Conference of Cantors, said that although there were some cantors who served as a congregation’s sole spiritual leader 10 years ago, “the numbers were so small that I didn’t report them to the Conference.”

The traditional rabbi-led synagogue model still prevails in the Union for Reform Judaism, which includes about 850 synagogues, and the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, which includes about 600. Together they account for 80% of American Jews who affiliate with a religious movement. But those who watch clergy job placements say the trend of hiring a cantor — the person who chants synagogue services — instead of a rabbi, is growing stronger.

It’s driven in large part, they say, by dwindling enrollments at the larger non-Orthodox rabbinical schools.

The Conservative movement’s flagship seminary in New York, for example, had an entering class of seven rabbinical students last year, compared to more than twice as many decades ago. And enrollment at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, which operates three campuses to train Reform rabbis, has fallen about 30% since 2008.

Cantorial leaders also note that seminaries in recent years have broadened training in ways that make it easier for congregations to picture a cantor where a rabbi once stood, offering classes in pastoral care and the analysis of Jewish texts that resemble those taught to rabbinical students.

“We have made a concerted effort to add these clergy skills,” said Greenwald. “Why? Because there are individuals who wish to commit to a life of Jewish service and are ready to lead.”

When they do lead a synagogue, do cantors get paid as much as rabbis? Within the Conservative movement, pulpit rabbis earn a mean salary of about $175,000, according to a 2021-2022 salary survey.

Lipton, who helps place cantors in jobs, said no one has crunched the data on the question. “Each position has a posted salary and the rest is up to negotiation,” he said.

Wanted: Rabbinical cantor or cantorial rabbi

It’s not the case that all cantor-led synagogues had embarked on a search for a rabbi, failed to find one, and then hired a cantor. Some Reform congregations, especially those that prioritize musical

programming, set out to find a cantor as their sole clergy. Others don’t care if they get a cantor or rabbi, and advertise their interest for either, say several people familiar with synagogue hiring trends.

In a related phenomenon, an increasing number of cantors are going back to school seeking rabbinical ordination, with many hoping to increase their chances of leading a congregation. Lipton said he knew of at least 32 cantors who now have both rabbinic and cantorial degrees.

One of the most well-known rabbis in the nation, Angela Buchdahl, who leads Manhattan’s Central Synagogue, was first ordained as a cantor in 1999, and then as a rabbi in 2001.

At the forefront of the trend is the Academy for Jewish Religion in Yonkers, New York, which created a Cantors to Rabbis (C2R) program in 2017 that has since ordained seven people – three this year alone. Six are currently enrolled.

AJR, said Cantor Michael Kasper, the academy’s acting CEO, who is also dean of its cantorial program, said it’s the only school in the country that has a program that grants rabbinic ordination specifically tailored to ordained cantors.

“Some of them want to ensure they can continue to work because as they get older, their voice is not as good,” he said. “Others want to learn more Torah and have no intention of giving up their cantorial job.”

Still others want the opportunity to be able to work as a rabbi or kol bo, he added, using the Hebrew term that indicates a person who serves in both rabbinical and cantorial roles.

One student in the program, Cantor Steven Hevenstone, 60, at the Dix Hills Jewish Center on Long Island, said he had already served as a kol bo when he was a cantorial soloist and the education director at Temple Shir Shalom in Duluth, Georgia, between 2003 and 2005.

“I believe in Jewish learning and Jewish growth,” he said of his decision to seek rabbinic ordination. “And there are synagogues now looking for someone who has both a cantorial and rabbinical degree.”

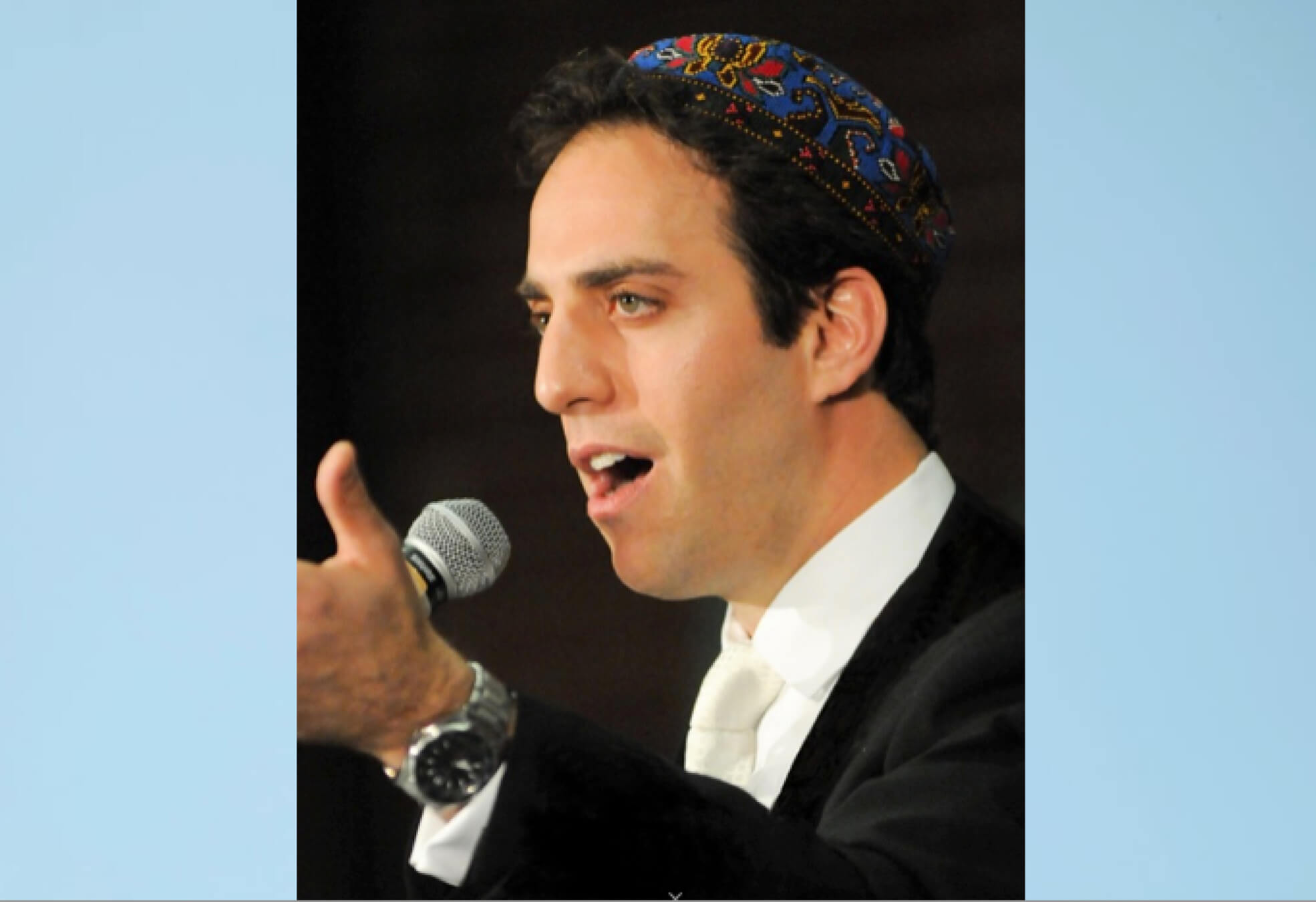

Cantor Michael McCloskey, 43, just graduated from the academy with rabbinic ordination after working 12 years as a cantor. Now cantor at Temple Emeth of Chestnut Hill in Brookline, Massachusetts, his congregants call him “Rabbi-Cantor Michael.”

He said he loves studying rabbinic texts, and that his congregants were asking him questions about Judaism and Jewish cultural traditions that he could best answer after obtaining the second degree.

“Having rabbinic ordination has made me a more sensitive and thoughtful cantor,” he said.

Kasper said graduates of the program are having no problem finding jobs: “There are more positions than clergy to fill them.”

Listen to That Jewish News Show, a smart and thoughtful look at the week in Jewish news from the journalists at the Forward, now available on Apple and Spotify: