Reporter's NotebookFrom a kabbalist’s grave to a destroyed kibbutz: Inside an IDF press tour

The stench of burned bodies stuck to my hair for two days, and I was uncomfortable parachuting in and out

A home in Kibbutz Be’eri, Israel, where Hamas terrorists killed 108 Israelis on Oct. 7, 2023. Photo by Laura E. Adkins

KIBBUTZ BE’ERI, Israel — The grave of a miracle worker is a strange place to meet for a tour of carnage. And yet, the official press visit last week to Kibbutz Be’eri, the Gaza border community where Hamas killed 108 people Oct. 7, began and ended at the tomb of the Baba Sali, a kabbalistic pilgrimage site.

How strange we must have looked, dozens of journalists from around the world, pulling up in taxis to the graveyard parking lot at high noon.

I heard a familiar voice speaking Hebrew in a quick staccato. A friend from college, now serving as a reservist in the IDF spokesperson’s unit. I tapped her on the shoulder, and we hugged; there’s nothing else I could really say.

Someone from the Government Press Office passed around waivers to sign, reminding us that we’re responsible for bringing our own vest and helmet. If a siren sounds, we’ll have 15 seconds to leave the bus, lie on the ground, and cover our heads. It doesn’t take a veteran war correspondent to know that emptying 50 people from a bus in 15 seconds is not realistic.

The GPO told me Oct. 23 that 1,950 journalists have poured into Israel to cover this war so far. On the short bus ride south from the grave in Netivot, I met correspondents from India, France, Greece and Italy. Someone stood up holding a poster and began to shout, and for a moment, I thought it was a protester who had somehow managed to get on board. But no, it was an IDF spokesperson, reminding us how many Israelis were killed, that Hamas is pure evil.

Quoting from a video that’s been making the rounds, he said, terrorists were asked: “Why did you kidnap babies? Why did you kidnap women?” The answer, he said? “To rape them.”

The tour I joined was on Friday, nearly two weeks after the massacre. The bodies had been removed, along with most of the signs of death. But people from ZAKA, Israel’s volunteer emergency-response organization, were still collecting remains from the rubble.

At first, it looked like a tornado had torn through the town — until you got close enough to see the stone walls pocked with bullets like a wedge of Swiss cheese.

Most of the journalists quickly formed a tight circle around someone from the kibbutz security team, who recounted grisly details of the events of what everyone here is now calling Black Shabbat. The IDF is supposed to be able to arrive within 30-60 minutes in the event of an attack, he said. Instead, it took 12 hours. Meanwhile, the kibbutz security team ran out of bullets.

I gave up on the crowded cluster to explore on my own.

When I was in 7th grade, my history teacher prepared us for a visit to the Holocaust museum in Washington, D.C., by saying we’d never forget the smell of all the shoes, or be able to describe it. At Be’eri, where Hamas terrorists set homes ablaze with people locked inside in their safe rooms, the stench of burned bodies and belongings that still hung in the air lingered in my nostrils and stuck to my hair for two days.

Besides our busful of correspondents, the only people in the kibbutz that once was home to 1,000 residents were about two dozen soldiers and ZAKA volunteers. Broken windshields scattered on the roads glittered in the afternoon sun. Flowers bloomed and still-young limes hung on half-burned trees. Airplanes and the sound of rockets mingled with birds singing like any other afternoon.

And 108 Jews were dead.

The front entrance of one home was littered with red roof tiles, dislodged by a rocket blast or rocket-propelled grenade. Clattering across the debris to venture inside transported me back to Berlin, where I visited in January. There, in a Jewish Museum installation called Shalekhet — Hebrew for “fallen leaves” — visitors clank across 10,000 gaping mouths cut into iron plates. It’s an equally uncomfortable experience.

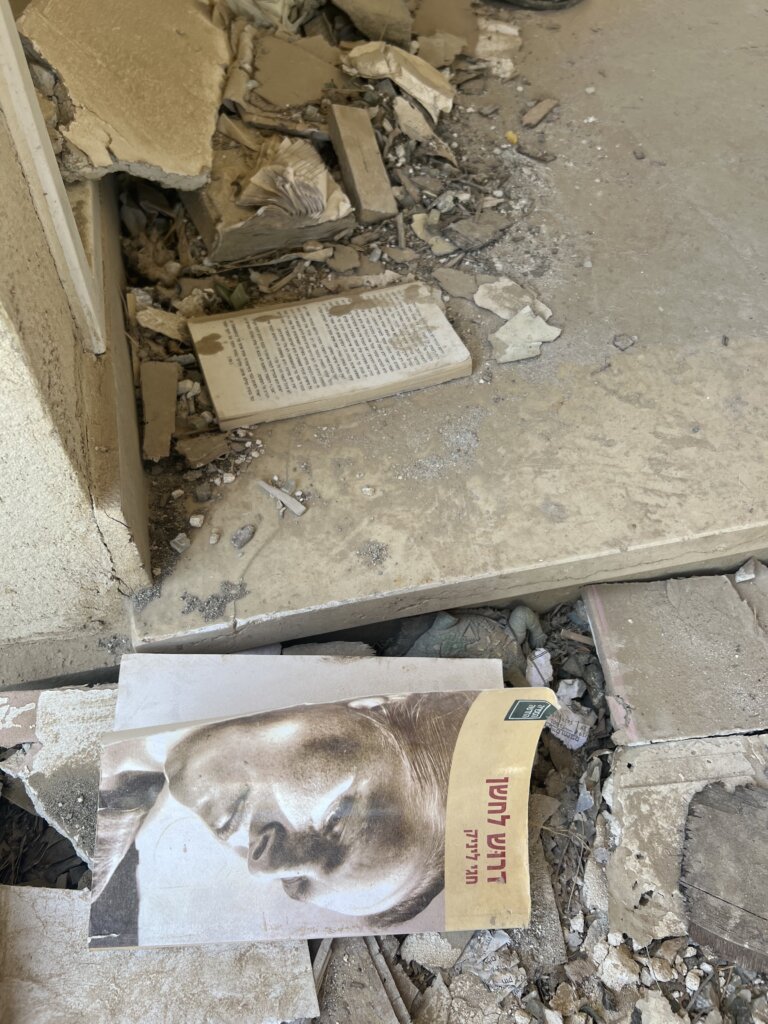

In another Be’eri home, I found a book called The Prompter laying on the floor. The novel, by the Israeli author Haggai Link, explores how we “integrate an experience of death into everyday life,” as the publicist put it, and how those left behind cope with their grief. Someone must have been reading it when the attack began. The cover had separated from the book, which was open to page 86.

There was pet food and water by the side of the road. The container was full: Either it’s been replenished since the attack, or there are no animals left to eat or drink. A sign, fallen to the ground, says, “Slow down! Speed bumps ahead.”

Suddenly, half a dozen soldiers rushed to the edge of the neighborhood. I feared they had found a terrorist somehow still in the community. Turned out they were posing for photos. A number of the correspondents I’d come with directed them to stand or crouch in various positions, at one point moving them to stand on a more cinematic-looking hill.

I felt a little like how I’d felt at Auschwitz when I traveled there with Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff early this year. A sanitized and cinematized version of our suffering. I made a snarky comment about falling for Israeli propaganda. I didn’t like how quickly the journalist I later realized wasn’t Jewish agreed with me.

On the way back, the bus pulled off to an area where several tanks and dozens of soldiers were stationed. When we arrived, they unfurled several fresh Israeli flags. A small child offered us cold Coke Zeros. A commander shooed off one journalist trying to take pictures of the tank’s insides.

I noticed an Israeli journalist standing off to the side with his arms crossed. He told me he had served in an artillery unit, and recalled being trotted out for this sort of thing, too.

I felt uncomfortable. I worried that some of my colleagues parachute in and out too quickly to understand the complicated past and future of this place. The extent to which Israel feels it must showcase the suffering of innocent civilians feels itself a little tragic.

Linik, the author of the open novel I found at that house in Be’eri, declared more than a decade ago that he was done with the rituals of Israeli Memorial Day, and would no longer stand by the grave of his brother, who was killed in a training accident, or listen to the siren, which he called a “deadened, faceless voice.”

“I have stood there with my own body so that my dead, for the duration of the 40-minute memorial, will be your dead,” he wrote in the newspaper Yediot Aharonot. “But after 44 years, I am tired of playing the role of your agent of death. I quit.”

We finished the trip where it had begun: at Baba Sali’s grave. I wandered off to use the restroom before the long ride back to Jerusalem. I must have looked strange, in jeans and a black bulletproof vest.

A soldier asked me in Hebrew if I knew where the rabbi’s grave was.

“Poh!” I replied. Here.

“No, I know that,” he said. “Where more specifically?”

“I don’t know, brother,” I confessed. “I’m just a journalist here from America.”