‘Schools I don’t want my kid to set foot on’: For some Jewish families, Oct. 7 upended the college application process

Jewish high school seniors are crossing dream schools off their lists and replacing them with colleges where they believe Jews are welcome

Students participate in a “Walkout to fight Genocide and Free Palestine” at Bruin Plaza at UCLA Oct. 25. Photo by Frederic J. Brown/AFP via Getty Images

Josie LaMere, a Jewish high school senior in Minneapolis, looked at 15 or 20 colleges before picking Occidental College in Los Angeles as her dream school. She was about to submit an early decision application when she learned that 59 Occidental professors signed a letter condemning Israel’s war in Gaza as “genocide,” without mentioning the Hamas massacres that prompted Israel’s attacks.

“I don’t know if I can learn from these teachers who are telling me that this is what I have to think,” she told her mother, Melanie.

Josie’s college counselor reached out to Occidental for reassurance. “It took eight days for them to get back to us with a non-answer,” Melanie LaMere said. “It was heartbreaking.”

So Josie never sent that application to Occidental. “My priorities have radically transformed,” she said. “Now, more than ever, I know I want a Jewish community wherever I go,” and a school where she will “feel safe, supported, and authentically me, as a Jewish person.”

The war on campus

Josie is one of many Jewish high school students for whom the college application process has changed since Oct. 7, when Hamas terrorists murdered 1,200 people and kidnapped 240 in surprise attacks on kibbutzim and a music festival near Israel’s border with the Gaza Strip.

Israel responded with a bombing campaign and ground invasion that Hamas officials in Gaza say has killed 15,000 people there. Many U.S. college campuses are now hotbeds of antiwar activism — and antisemitic incidents — as pro-Palestinian student groups and professors blame Israel for the war without condemning Hamas.

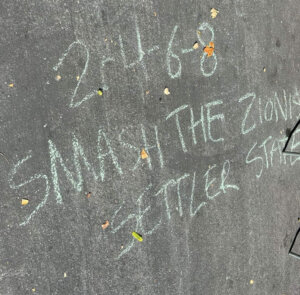

Jewish students have been targeted in dozens of incidents. At Stanford, an instructor ordered them to stand in a corner, then labeled them “colonizers.” At Manhattan’s Cooper Union, Jewish students barricaded themselves in a library while pro-Palestinian activists pounded on the windows.

The clashes have left many Jewish families afraid to send their teenagers away to campuses where they fear they will be harassed, isolated and subject to bias by professors — like those at Occidental — who have declared their antipathy to Israel. Nearly 53,000 people have joined the Facebook group Mothers Against College Antisemitism since its Oct. 26 launch.

And it’s all happening just as college applications are coming due. Some schools have rolling admissions, but many deadlines are in November, December and January.

Applying to college in the U.S. is a fraught process no matter what, as students decide where to go, which schools will take them and what they can afford. But the Israel-Hamas war and campus antisemitism — on the rise well before the current war — have added layers of anxiety. Many Jewish high school students have crossed dream schools off their lists and sought advice from Hillel about Jewish life on campus.

“The calculus has changed,” said Jodi Furman, a college admissions consultant and founder of College Smart Start.

Colleges, for their part, can’t seem to please anyone. Jewish families and pro-Israel groups accuse them of allowing pro-Palestinian activism to threaten Jewish students. But when administrators try to curb the most aggressive protesters, civil rights and pro-Palestinian groups charge them with stifling free speech and dismissing the suffering of the oppressed.

To be sure, not all Jewish students have altered college wish lists since Oct. 7. But it’s easy to find many who have. To see how perceptions and priorities have shifted, the Forward interviewed 30 parents, students, college advisers, school administrators and others. Here are their stories.

Three kids, three college stories

Michal Juran, a dual Israeli-American citizen living near Syracuse, New York, has three children who illustrate various ways the Israel-Gaza conflict is playing out on U.S. campuses.

Her eldest is happily ensconced at Brandeis, a historically Jewish university that expressed solidarity with Israel after Oct. 7, then banned Students for Justice in Palestine from campus over its support for Hamas. “The administration spoke up right away,” Juran said, “and showed other schools what should be done.”

Juran’s middle child is a University of Rochester freshman, but plans to leave at the end of the semester because she doesn’t feel safe there. Her mother says the campus hosts “nonstop” pro-Palestinian rallies, and the administration’s initial message about the war failed to condemn Hamas, though an apology came later. (University spokesperson Sara Miller told the Forward that new guidelines “require that protests are conducted in ways that allow our students to pursue their educational goals without disruption in a safe and hostile-free environment.”)

Meanwhile Juran’s youngest, a high school senior, planned to apply early decision to Middlebury College in Vermont, but changed his mind because of pro-Palestinian activism there. His second choice was Cornell, which he nixed after a student was arrested there for making death threats against Jews and a professor said he was “exhilarated” by the Hamas attacks.

“It just reached a limit of what he wanted to deal with,” Juran said. “He just gave up and decided to go somewhere else,” with the State University of New York’s Binghamton campus a likely top choice.

‘An environment where I feel welcomed’

Abby Moskowitz, mother of a high school senior in New York City, said their family is not particularly religious, but she wants her son “to be with people that accept you.” She added: “There are schools I don’t want my kid to set foot on. My own alma mater, UCLA, is a disgrace.”

Complaints about UCLA have cited online harassment of Jewish students, an allegation from Chabad that pro-Palestinian protesters carried knives, and “celebrations” of Hamas terrorism that led 363 faculty members to sign a letter demanding action by the administration. By the time UCLA Chancellor Gene Block and other UC officials issued a statement denouncing antisemitism (and Islamophobia), Moskowitz’s son Noah had already replaced his UCLA application with an early bid for Washington University in St. Louis.

“I had postponed my submissions because I wanted to see how the administrations handled antisemitic situations on campus,” Noah said. “I have since dropped a handful of colleges from my list. I’m looking for a large Jewish student population and an environment where I feel welcomed.”

Nomi Goldwasser Landis’ daughter crossed off six of her 10 schools, including the University of Pennsylvania, which has just been sued by two Jewish students alleging a hostile environment. “We were fairly committed to doing whatever we could to apply for scholarships and make (UPenn) happen for her,” said Landis, who lives in Cleveland. “It’s a good school, close to where we live, but with everything that’s going on there, we didn’t feel it was worth the money.”

The University of Pittsburgh is now a top choice. “We looked at the places where the administration took a strong stance, but if there was violence or demonstrations or propaganda clearly posted with the administration not doing anything about it, then we weren’t comfortable going,” Landis said.

What the colleges say

College administrators say there’s only so much they can do to limit campus strife. Protests and statements, no matter how controversial, are considered free expression and free speech, protected in many cases by the First Amendment and germane to academic freedom, as long as they do not entail or advocate violence. Many schools have received complaints of both Islamophobia and antisemitism.

Occidental College, when asked how Jewish students would fare in classes taught by professors who publicly condemn Israel, pointed to a message from the school’s president, Harry J. Elam Jr., noting that faculty are obliged to provide “even-handed treatment in all aspects of the teacher-student relationship.”

The message also lamented the loss of life on both sides of the Israel-Gaza conflict, outlined resources for Jewish and Muslim students, and condemned antisemitism, Islamophobia and other forms of bigotry. Other schools, like Columbia, a site of recurrent pro-Palestinian protests, have made similar statements, issued apologies, set up task forces and banned pro-Palestinian groups.

Several families lauded Tulane University, where 40% of students are Jewish, as an example of a school where administrators responded appropriately to a high-profile rally in which three students were injured. Police were called in, arrests were made, and security and support for students was stepped up. Tulane President Mike Fitts also condemned Hamas early on.

Tulane spokesperson Michael Strecker said it’s too early to know whether more students will apply as a result — though they had an increase in applications this fall — but said the school has “received notes of appreciation from Jewish families and others.”

Other POVs: Unconcerned, defiant — or aligned with Palestine

A recent study by the Anti-Defamation League and Hillel International found that 73% of Jewish college students said they had experienced or witnessed antisemitism on campus this fall — up from 32% in 2021.

But in some families, parents are more worried than students. New Yorker Elizabeth Rand, the founder of Mothers Against College Antisemitism on Facebook, said her high school senior son does not share her concern.

“I said to him, ‘If you get to UPenn and you see what’s going on and people are shouting hatred at Jews, what are you going to do?’” she recalled. “He said, ‘I’m going to start a counterprotest.’ So obviously this is an individual decision between students and their families. My kid is willing to get out there and counterprotest. Other students are like, ‘No way.’ It really depends on the kid.”

Joey Block, of Oak Park, Illinois, who’s applying to schools in his home state as well as Colorado, Oklahoma, West Virginia and Michigan, says he’s “been thinking a little more about what it means to be Jewish over the past seven weeks or so, but it’s not the deciding factor.”

His mother Marta, on the other hand, grew up in Kentucky and was often told by people that she was the only Jew they’d ever met. She wonders what that might feel like for her son: “Are you going to be one of the only Jewish kids on campus? Are you going to have to explain every holiday, every time?”

Of course, some Jewish students’ sympathies lie with Palestine. While campus antisemitism might not discourage them from applying to a college, they might face pushback from the other side once they arrive. Clay Robison, a Jewish student at the University of Florida, told UF’s student newspaper that he was called an “embarrassment to the Jewish community” over his public support for the Free Palestine movement.

Rejecting small liberal arts colleges

Davina Fogel’s child had planned to apply to small liberal arts colleges like Vassar, Quinnipiac and Skidmore, but they’re no longer an option “because of the way they handled antisemitism and the rhetoric from professors.” Instead, the University of Connecticut, despite being a big school, is now a top choice. Fogel says UConn’s administration “has been proactive, with no professors stirring the students up,” and the campus chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine has exercised its “right to free speech without hostility or harassment.”

Jennifer Morgan’s daughter is only a high school junior, but she’s already rejected several small liberal arts schools along with some in the Ivy League. “We’re Reform Jewish, Democrats, liberals, and always considered ourselves fairly progressive,” said Morgan, who lives near Philadelphia. “We’re trying to stay true to a lot of our ideals; at the same time I want my daughter Alexandra to be safe on a campus and not attacked or isolated.”

Alexandra said what she’s seen happening on campuses since Oct. 7 has “been a real eye-opener for me.” She emphasized her support for free speech and “the right to hold your own opinions.” But “there is a line to be drawn. Colleges that I thought were safe have been protecting those who cross the line between free speech and threats.”

Considering Yeshiva University

Rabbi Abraham Cooper, director of global social action for Simon Wiesenthal Center, said his organization has been “deluged” with questions from parents about campus safety. The center plans to release a study in January of 25 prestigious colleges, examining whether they responded “appropriately.”

“Kids coming out of high school and their parents are saying, ‘Maybe I should go to Yeshiva University or even some of the Catholic schools that have stepped forward,’” Cooper said, referring to a consortium of schools that invited Jewish students to apply.

Robyn Ackerman and her husband had hoped their daughter, who attends Ida Crown Jewish Academy in Chicago, would “go to a university that was not Yeshiva University,” in order to experience a school outside the Jewish world.

But in October, “our opinions about where she will apply turned 180 degrees,” Ackerman said. Fortunately, her daughter is excited about the prospect of attending Yeshiva’s Stern College for Women — and now Ackerman just hopes the school doesn’t become a target for antisemitic outsiders.

Stacy Nicolau’s daughter Julia, a high school senior in Naples, Florida, consulted Hillel’s college guide, which ranks schools by how many Jewish students attend, to find schools with significant Jewish populations. She already had a few on her list, but added Tulane, the University of Miami, the University of Florida and Florida State.

“It became a priority for her, even to the point where she was like, ‘I want to rush the Jewish sororities, I just want to be with our people,’” Nicolau said.

‘Taking back their power’

Furman, of College Smart Start, says it remains to be seen whether concern about antisemitism “translates into actual decisions and behavior.” Ultimately, she predicts many will say, “My kids are going to the best school they can get into academically and we’ll deal with the rest of it.”

She also knows students, like Rand’s son, who won’t be intimidated. “They’re taking back their power,” she said. “They’re saying, ‘I will not be told where I cannot be. I worked this hard. I want to go to this school and I am not going to let a few bad actors or incidents determine where I belong.’”

On the flip side, Cooper, of the Wiesenthal Center, said families should ask whether kids should walk into a “confrontational setting just because I would be the fourth generation to go to an Ivy League school. Why should we put our children into, and very often pay top dollar for, a scenario in which they end up being harassed?”

Optimism for the future

Rabbi Dov Greenberg, who runs Stanford’s Chabad, says he’s seen a “noticeable increase” in inquiries about safety and inclusivity since the headline-making incident where an instructor made Jewish students stand in a corner.

Despite the challenges, Greenberg says this is “also a period of significant awareness and potential for positive change. I tell them that the Jewish community on campus is resilient, supportive, and actively engaged in dialogue with university administration to address these concerns.”

Looking ahead, Greenberg hopes that Stanford, “having revolutionized technology, now faces its moment to revolutionize its moral stance.”

Furman is similarly optimistic. “I’m hoping for my seniors and for the world,” she said, “a kinder, gentler place by the time these students enter campus in August.”