Special Report‘Astonishing’ volume of investigations tests legal protections for Jewish students

The Department of Education has opened 48 cases tied to antisemitism at colleges and universities since Oct. 7, most related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

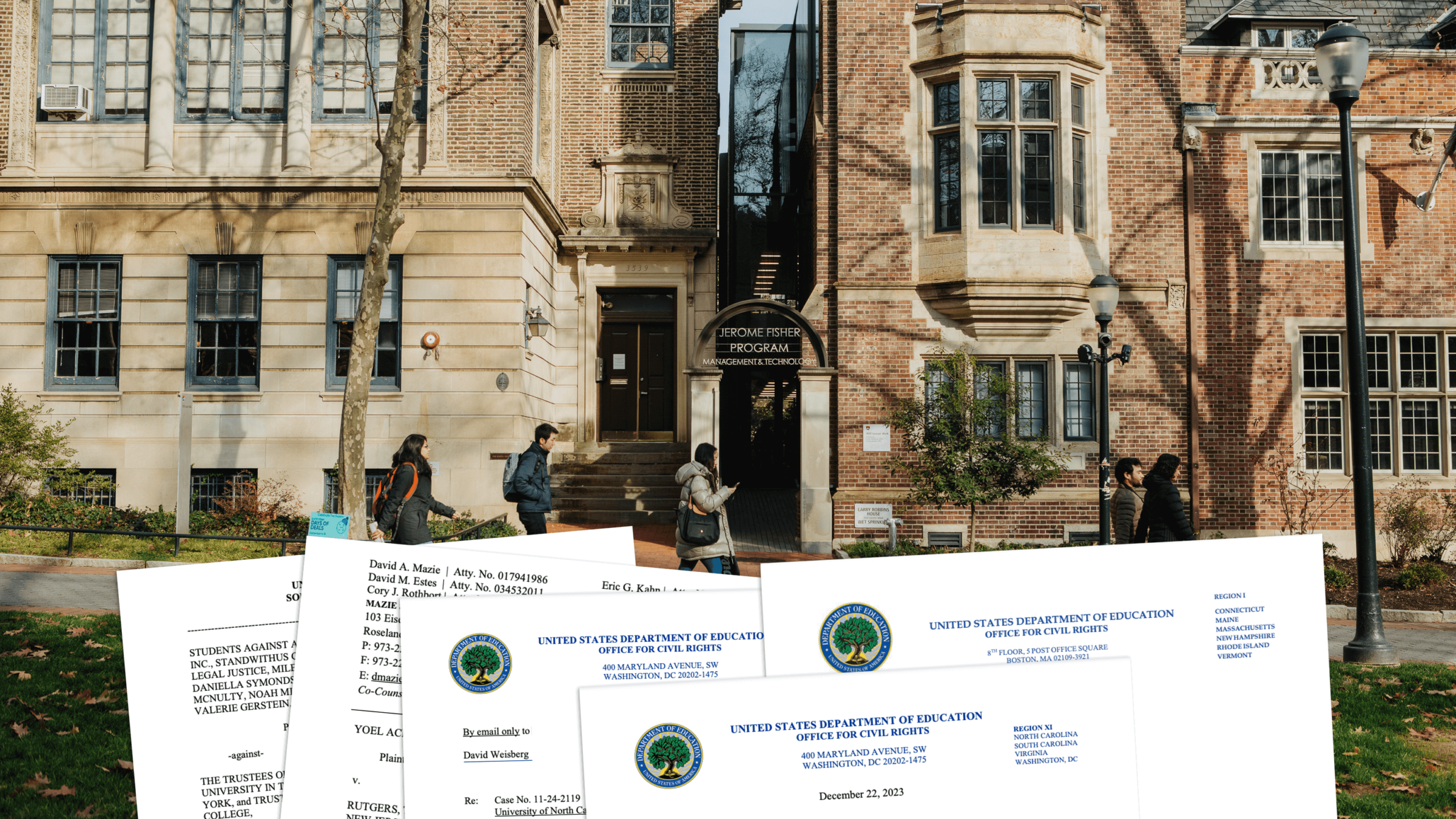

The University of Pennsylvania, pictured above, is one of dozens of colleges and universities that has been subject to federal investigations and lawsuits over allegations of antisemitism since Oct. 7. Graphic by Arno Rosenfeld/The Forward with photo by Getty Images

A federal investigation or lawsuit related to antisemitism on college campuses has been opened or filed nearly every other day on average since Oct. 7, according to a Forward analysis.

The complaints describe a range of incidents, including white supremacist flyers at Montana State University and a drunken assault at the University of Tampa. Many complaints center on speech related to Israel. A student at the New School said he heard someone comment, “I wish you had been in Israel on Oct. 7 so you would have been raped, too.”

This unprecedented flurry of civil rights lawsuits and Education Department investigations reflect spikes in antisemitic and anti-Israel incidents nationally during the Israel-Hamas war. But it’s also driven by an increased reliance on a legal doctrine — rooted in the idea that Zionism is part of Jews’ “shared ancestry” — that has been crafted to expand legal protections for Jewish students, especially those who support Israel.

The Biden administration has encouraged Jewish students who feel targeted by increasing hostility toward Israel and its supporters on many college campuses to look to the department for protection.

“This became an all-hands-on-deck moment after the terrorist attack,” Education Secretary Miguel Cardona said at a public briefing this month. “No student should ever feel that they are going into a learning environment where people are openly spewing hate.”

The Department of Education is currently looking into 46 cases related to shared ancestry at higher education institutions, along with dozens more at the K-12 level, although they represent a tiny fraction of overall civil rights investigations. But it is difficult to discern the nature of each complaint, because the department makes little information public, and several cases allege Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism since Oct. 7. Harvard, for example, is being investigated over claims of both antisemitism and anti-Muslim bias.

The cases are often called OCR or Title VI investigations, referring to the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights, which oversees them. Schools are compelled to cooperate or risk losing massive sums of federal funding.

In addition, there are at least nine federal lawsuits against universities tied to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict — most also alleging antisemitism — making their way through the court system.

The caseload takes so long to adjudicate, and the number of final resolutions to date so sparse, that it’s not clear whether the federal government and courts can deliver the relief that students and their supporters are demanding.

But proponents of the litigation strategy say that more complaints and lawsuits are in the works, and that the escalation in campus antisemitism deserves an aggressive legal response.

“Oct. 7 just poured fuel on a fire that was already out of control,” said Mark Ressler, an attorney who is suing several Ivy League universities on behalf of Jewish students. “Our view was that the appropriate way to address antisemitism on campus was to force universities to do what they’re required under federal law.”

Even as some critics warn that some of the complaints are based on flimsy allegations, these remedies have offered a degree of validation for some Jewish students and the advocacy organizations supporting them.

Katy Joseph, deputy director for faith-based partnerships at the Education Department, recalled meeting with a Yeshiva University student whose parents immigrated from the former Soviet Union and were flabbergasted by the country’s civil rights apparatus.

“They said, ‘You’re meeting with someone from the federal government about addressing antisemitism — who could imagine that the federal government would care about what Jewish students are experiencing?’” Joseph recounted.

A new doctrine covers Jews — and possibly Israel

Investigations into alleged antisemitism in American schools is a relatively new phenomenon for the Education Department because religious discrimination falls outside its purview and, until 2004, that is how it categorized discrimination against Jews.

This had long frustrated some Jewish civil rights leaders, who felt that Jews were getting short shrift from the federal government for viewing them too narrowly as a religious group.

When Ken Marcus took over the department’s civil rights office during the George W. Bush administration, he started looking for test cases for a new category of “shared ancestry” that would allow officials to investigate cases that touched on religion. He found one when a Sikh child in New Jersey was beaten by classmates who saw his turban and taunted him as “Osama,” a reference to the infamous Muslim terrorist.

Marcus believed that the discrimination wasn’t strictly religious in nature because the bullies weren’t intending to go after the boy’s Sikh identity. And it wasn’t obviously racial, either, since it was the turban that had drawn the bullies’ attention.

He authorized the department to investigate these types of cases under its authority to prohibit discrimination based on race or national origin. Every subsequent administration has agreed that these cases fall under the department’s purview.

More controversial is the question of what, exactly, constitutes discrimination against Jews based on their shared ancestry. Marcus and many Jewish advocacy groups have taken the position that anti-Zionism — opposition to a Jewish state in Israel — is often antisemitic because many Jews identify with Israel as part of their shared ancestry.

Organizations like Hillel have made this argument to colleges and universities for several years, with mixed success, and Marcus successfully lobbied the Trump administration to require the Education Department to use a definition of antisemitism that classifies much anti-Zionism as antisemitic.

Many recent complaints reflect this view. A Rutgers law student, for example, taking issue with a text group chat in which other students were expressing support for the Palestinian cause, filed a complaint with the department. And a lawsuit against Harvard objects to a screening of Israelism, a film about American Jews who have become disillusioned with Israel, as antisemitic.

Shabbos Kastenbaum, one of the students suing Harvard, said he was especially upset that one of the panelists who spoke after the screening suggested that Jews had internalized the trauma they suffered during the Holocaust and were now lashing out against the Palestinians. “The crux of the complaint is that someone is engaging in antisemitic tropes,” he said.

Some of the smaller number of complaints filed on behalf of Arab and Muslim students also reference incidents involving speech about the conflict. San Diego State University is under investigation for an email sent to students following Oct. 7 that condemned the “horrific” Hamas attack, while expressing sympathy for both Israelis and Palestinians who had been killed.

‘A very low bar’

Advocacy groups often herald the Education Department’s opening of an investigation as evidence that their case has merit. That used to be the case, according to Miriam Nunberg, a former civil rights staffer at the department, who told JTA that a decade ago her team would only open investigations if the complaints seemed serious enough.

But now the policy is to open investigations into any complaint that claims a school violated a civil rights law over which it has jurisdiction, as long as the alleged violation took place within the last six months.

“The opening of an investigation does not mean the law was violated,” said a senior Education Department official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because the department did not permit her to speak publicly on the matter. “There’s a very low bar for opening complaints.”

The law also allows anyone to file a complaint, including those who have no affiliation with the school or firsthand knowledge of the incidents. Advocates say that’s important, so the onus is not on a potentially vulnerable victim of discrimination to report a problem, and because civil rights violations have a negative impact on society — not just on the handful of people directly impacted.

But this low bar, critics point out, also means the department must open cases even when there is not a clear victim of discrimination, or when investigators do not believe the claims have merit.

If the “shared ancestry” category has made it easier to file a suit against a college, so has the fact that no one in an alleged incident has to go to school or work there to file a complaint against it. Tulane, for example, is being investigated over the assault of a Jewish student at a protest although all four people arrested in the incident were unaffiliated with the New Orleans university and the student’s attorney has said the school is not responsible. Two years ago a single anonymous individual was responsible for nearly 40% of the 18,804 investigations that the department opened, mostly centered on allegations of sex discrimination based on the person’s review of school data about athletics.

Who’s filing these cases?

Though the department doesn’t reveal the details of what it’s investigating, many organizations have shared complaints they have filed about antisemitism in recent months. The Forward created a database of all known federal investigations and lawsuits based on the limited information released by the Education Department and lawsuit announcements. Though the department began releasing a list of its shared ancestry investigations in November, it does not share details of those cases, including whether the allegations involve antisemitism.

According to the Forward’s review, most of the complaints filed by organizations came from legal advocacy groups like the Brandeis Center and the Lawfare Project, which focus on defending Jewish students and Israel.

But these groups have a higher standard for taking a case than some other complainants. Alyza Lewin, president of the Brandeis Center, said the organization has declined to represent several students who may go on to file some of the weaker complaints independently.

“They’re filed by people who are unhappy, who are upset and who feel that they want to do something, and they’re very well-intentioned when they file them, but they may very well be filing complaints that might not have a successful resolution,” Lewin told JTA in a piece published Thursday detailing the recent uptick in cases.

More partisan actors have also joined the fray, including Campus Reform, a news outlet run by a conservative training center whose editor has filed at least nine federal complaints accusing various universities of antisemitism.

Cardona said that his team knows that some of the antisemitism complaints are coming from people who may have political motivations, but that doesn’t change the department’s obligation to investigate.

“I can’t say that we’re not aware of it,” he said. “There are a lot of things that have become politicized in this country and at the end of the day it’s our responsibility to make sure we’re thinking about the students.”

‘Vindicating their rights’ in court

While the Education Department investigates potential violations of federal law, complaints filed with the agency are not lawsuits. That means students or outside organizations don’t need to hire lawyers to sue a college or university. But it also means adjudication may be very slow, and they are unlikely to receive monetary damages even if the school is found to have violated their rights.

Of the 10 lawsuits filed against higher education institutions since Oct. 7 related to antisemitism or Israel on campus, four have been filed by one law firm, Kasowitz Benson Torres, whose lead partner Marc Kasowitz served as former president Donald Trump’s longtime personal attorney.

Ressler, the attorney overseeing the cases, has sued Harvard, New York University, the University of Pennsylvania, Columbia and Barnard, and said he is looking for more schools to sue. Ressler said his firm started recruiting student plaintiffs well before Oct. 7. Several individuals, who Ressler described as prominent Jewish leaders but declined to name, approached Kasowitz over the summer and told him they wanted to use the courts to fight antisemitism, including campus diversity initiatives they found problematic.

Federal lawsuits generally supersede administrative complaints, like those made through the Education Department, where officials said they have closed investigations into Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania after those schools were sued.

Ressler said litigation, far more effectively than filing a complaint with the Education Department, can force college administrators to hand over emails and other evidence of potential discrimination, and to defend themselves in public.

“American citizens vindicate their civil rights by going to federal court,” he said.

‘Pleading’ for resources

It can take years to resolve a complaint at the Education Department. Investigators are handling an average of 50 cases each compared to 36 cases two years ago and fewer than 10 each during the Bush administration.

Education Department officials and Democrats, along with some Jewish advocacy groups, have been lobbying to increase funding for the department’s civil rights office, arguing that it needs more investigators to handle the caseload and require schools to better protect students. The office currently receives $140 million in annual funding and has requested an increase to $177 million, although an outside coalition of civil rights groups wrote a recent letter calling on Congress to double its allocation to $280 million.

“It is astonishing to me that the complaint volume is so high,” said the senior department official. “And we have been pleading for years for Congress to increase our budget.”

Congressional Republicans have held hearings and launched investigations into campus antisemitism, but generally oppose increased funding for the department, calling for overall cuts to the federal budget. Marcus said the funding question was largely a partisan battle, and that only a tiny fraction of any new dollars would go toward addressing antisemitism because most of the office’s 19,000 annual cases are about discrimination against students based on gender and disability.

“Antisemitism cases — even post-Oct. 7 — are such a small percentage of OCR’s total caseload,” said Marcus, who now runs the Brandeis Center, which has filed at least four complaints with the department since October. “Antisemitism should be left out of this.”

Liz King, with the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, a coalition that sent the letter to Congress demanding more funding, said that the “shared ancestry” cases — including those about antisemitism — represent some of the most time-consuming.

“We really resent the idea that more complicated cases would fall to the bottom of the pile,” she said.

Violet Fearon contributed to this project.