How these 29 last names became a cheat code for researchers surveying American Jews

Can you guess which names make the list of distinctive Jewish last names used by researchers?

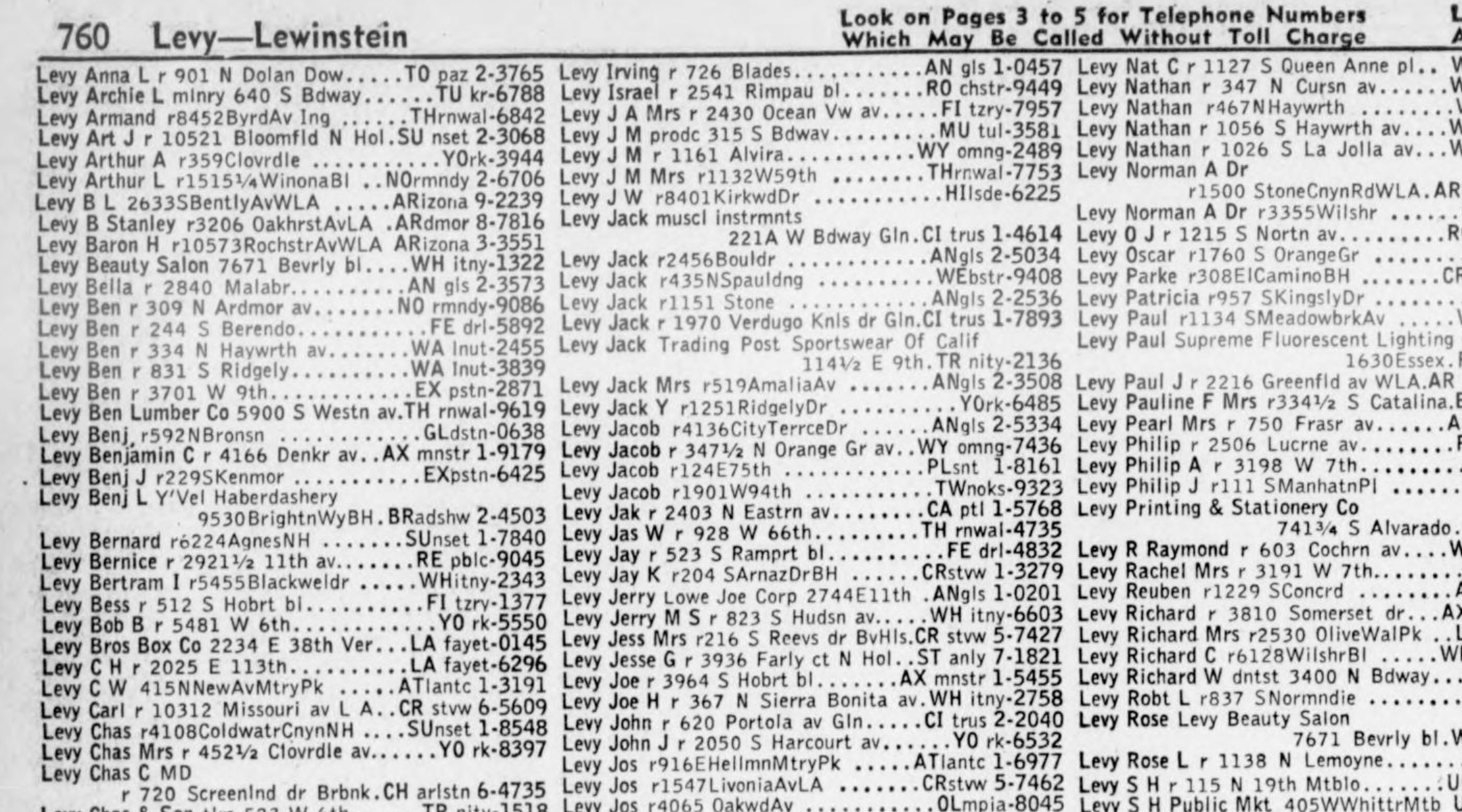

A screenshot of a page from a 1947 Los Angeles area phone book.

(JTA) — Ira Sheskin is one of the most prominent demographers of American Jews. A professor at the University of Miami, Sheskin helps Jewish communities across the country carry out complicated population surveys. He sometimes works for businesses, too, and several years ago, a major kosher poultry company turned to him with a quandary.

The company had convinced Publix Super Markets to stock its kosher chicken products, but not in every store. In Birmingham, Alabama, the company had to pick just one of Publix’s several local branches. But how to pick the one closest to the largest number of Jews?

The way to obtain the most accurate results would be through making phone calls or even sending letters to a very large number of people across Greater Birmingham, asking if they are Jewish as part of a randomized survey. But it would be too expensive.

Instead, Sheskin opted for a trick that Jewish demographers have been relying on for generations: checking the phone book for distinctive Jewish names.

“Within three miles of this Publix location, there are 20 households with a distinctive Jewish name, and within three miles of this other Publix, there are 150 households with distinctive Jewish names. It’s clear which Publix the product should go in,” Sheskin said.

But what is a distinctive Jewish name? As it turns out, researchers have a list of 29 last names that are so common among Jews in the United States, and so uncommon in the rest of the population, that they can be used to draw demographic conclusions.

Can you guess which names make the list of distinctive Jewish last names used by researchers?

Highlight hidden text below to see the answers:

1. Berman 2. Caplan 3. Cohen 4. Epstein 5. Feldman 6. Freedman 7. Friedman 8. Goldberg 9. Goldman 10. Goldstein 11. Greenberg 12. Grossman 13. Jaffe 14. Kahn 15. Kaplan 16. Katz 17. Kohn 18. Levin 19. Levine 20. Levinson 21. Levy 22. Lieberman 23. Rosen 24. Rubin 25. Schwartz 26. Shapiro 27. Siegel 28. Silverman 29. Weinstein

Not everyone with one of these last names is Jewish, and not all Jews in the United States — not even close to a majority of Jews — have one of them. An obvious issue is that the list consists of entirely Ashkenazi surnames, and would do poorly for identifying, for example, Persian, Israeli, or Russian Jews in the United States, which is a growing concern as American Jewry becomes increasingly diverse. But there’s still enough of a pattern to extrapolate total Jewish population estimates in most places using these names, according to Sheskin.

“People will say, ‘I know a guy named Levy who isn’t Jewish’ or ‘I know a woman named McMahon who is Jewish,’ and, look, on a one-by-one basis, you’re not going to predict Jewishness 100% of the time,” Sheskin said. “If a person’s name is Richard Miller, they could be Jewish, you never know. But here’s the point: Collectively, it works.”

A team of computer scientists recently used the set of distinctive Jewish names to determine roughly how many of the authors whose texts appear in artificial intelligence training data are Jewish. “The method felt both surprising and intuitive,” said one of the computer scientists, Heila Precel. In medical research, scientists testing medicines have turned to the so-called DJNs when they need to figure out which study participants are likely Jewish.

The distinctive Jewish names technique is most commonly used to find respondents for surveys of local Jewish communities.

Ideally, researchers would never need to go by last name. They would dial randomly from a list of local phone numbers and ask the person on the other end if they’re Jewish or not. If they are Jewish, they are asked survey questions, and if they are not, they’re screened out.

In the largest and wealthiest Jewish communities, such as New York, Miami, and Los Angeles, researchers do a lot of random calling or a combination of phone calls and mailed questionnaires. But even in those communities, screening for Jews is a major challenge. Assuming Jews are 2% percent of the population in a certain area, researchers have to screen 50 people to find one Jew or 150,000 people to find 3,000 Jews. And that’s assuming everyone picks up the phone.

So instead of contacting anyone and everyone, researchers focus on people with distinctive Jewish names.

“Getting a representative sample is tremendously expensive, very time-consuming, extraordinarily difficult, and just grotesquely inefficient,” said Matthew Boxer, a research professor at Brandeis University’s Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies. “If you can make that process more efficient, you should do so.”

The problem is especially challenging in places with small Jewish communities like in the Scranton area of northeastern Pennsylvania, which recently hired Boxer for a survey. He had to rely on distinctive Jewish names.

“We did the best we could with the resources that were available. They can’t afford to be spending millions of dollars searching for Jews,” he said.

Previous research has shown that people with names from the distinctive names list make up about one in 10 Jews in most areas of the United States. So by checking how many people in a given area have one of these names, it’s possible to produce a rough estimate of the total Jewish population.

The list of distinctive Jewish names isn’t a secret, but it’s almost impossible to find online. People tend to be surprised to learn that this is an indispensable tool in Jewish demographic research, Boxer said.

“When you’re studying the Jewish community, it’s one of these situations where nobody knows how the sausage is made,” Boxer said. “People who hear about this method tend to react in one of two ways: Either, ‘That’s brilliant, what a wonderful way to be able to find Jews to participate in research,’ or, ‘That’s going to bias your results.’”

Bias would be a major problem for surveys, for example, if Jews with distinctive names tended to answer standard questions about their Jewishness differently than those without distinctive names. A few years ago, Boxer conducted a study to see if there is indeed a difference.

“What we found is that it didn’t matter what your name was, there were no differences. If you’re a Cohen or a Smith has no bearing on how connected you feel to the Jewish community, whether you seek out news about Israel, whether you join a synagogue, whether you do Jewish cultural things, eat Jewish foods, study Jewish texts, none of it makes a difference based on name.”

Still, skepticism of the technique remains, and Boxer acknowledges it’s important to use it with care.

“We have to represent everybody, especially the people who tend to be underrepresented, and there’s a danger of people who don’t have distinctive Jewish names being underrepresented. That’s why I don’t rely exclusively on distinctive Jewish names to find people. It’s a method that we use to keep the costs down for the Jewish organizations that we work with,” Boxer said.

The technique was originally devised in 1942 by a researcher named Samuel Kohs, who was charged at the time with assessing the recreational and cultural needs of the Jewish community of Los Angeles. He made a list of the most commonly appearing names in the files of Los Angeles’ Jewish federation. He then found that a set of 35 last names accounted for about 12% of names appearing on the Los Angeles list and on registries maintained by various other federations. Further research showed that 70%-92% of people with any one of 35 last names were Jewish.

These ratios have largely held to this day, although Sheskin has refined the list down to 29 names, plus variations.

Sheskin is currently using the technique as part of a new effort to estimate the Jewish population in every county in the United States for the American Jewish Year Book. Where there are large concentrations of Jews local federations have carried out expensive demographic surveys, so existing data is accurate and current.

But for his new project, Sheskin’s goal is to get better numbers for the many places where Jews are too few to have been counted.

“When you take someplace like Little Rock, Arkansas, you’ll never have an accurate count because that federation can’t pay for the survey,” Sheskin said.

Even for his project, the technique has its limits. In one county in Louisiana, for example, Sheskin found a high number of Levys but few other distinctive Jewish names. A ratio like that is unlikely unless those Levys aren’t Jews. Sheskin assumes that the situation is a result of there being many descendants of people who were enslaved by a Jew with the last name Levy.

He ended up doing some calculations comparing the numbers of distinctive Jewish names in that county (besides Levy) to the rate in other counties and to the national average. “Sometimes, I have to do a little bit of finagling with it. But in the end, we’re going to come up with estimates of how many Jews there are,” Sheskin said.

Sheskin has been working with distinctive Jewish names since the 1980s and over time he has created new lists for use in more limited situations. In total, he has more than 1,200 names which he keeps in a Word document and amends regularly, including when this JTA reporter, interviewing him about the list, suggested adding an alternate spelling of his own name.

There’s a list of hundreds of highly Jewish names that aren’t very common, or at least not as common as the core 29 are, in the United States. These include names like Fingerhut, Cooperman, and Elkayim. He has lists for Sephardic, Russian, and Persian Jews. He also has a list for Jews from Spanish-speaking countries because they have distinct spellings of otherwise common Jewish names, such as Goldsztajn, Fridman, and Epelbaum. Finally, there’s a special list of first names, because there’s a high likelihood that someone named Mendel or Ofra, regardless of last name, is Jewish.

It’s on that last list where this reporter noticed the name Asaf, but not Assaf. Upon alerting Sheskin, an addition was made — a small, spontaneous contribution to social science.

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.