ADL chief backs campus crackdowns. As a student, he stood up for free speech — even by antisemites

At Tufts in 1992, Jonathan Greenblatt urged students to engage with a Black nationalist who called Jews ‘bloodsuckers’

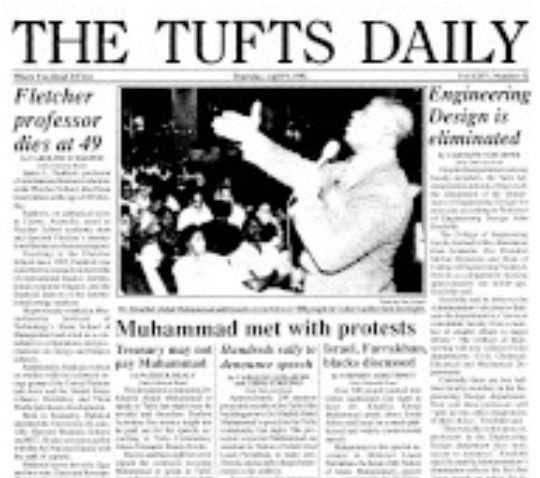

As a student journalist at Tufts, Jonathan Greenblatt, Class of 1992 and future CEO of the Anti Defamation League, stood up for free speech while fighting against antisemitism. Graphic by Odeya Rosenband. Screenshots from Tufts archives.

One April evening around Passover, around 200 students put their books down to stand up to antisemitism at their elite private university.

A campus newspaper reported that a Jewish student feared for her safety. Another student’s car had been pelted with rocks. And signs at the Islamic center were torn down.

Jonathan Greenblatt was among the speakers at the candlelight vigil organized by Hillel and a separate pro-Israel student group: “There‘s only one side to be on,” he told the crowd, according to the student paper. “The side against bigotry, prejudice, and antisemitism.”

The school was Tufts, not Columbia; the year was 1992, not 2024; and Greenblatt, now CEO of the Anti-Defamation League, was then a senior at Tufts, a columnist for a different student newspaper — and an ADL intern.

The campus just outside Boston had been sharply divided over a speech by Khalid Abdul Muhammad of the Nation of Islam about Israel and apartheid South Africa. Muhammad, a fiery Black nationalist who later proved too extreme even for the antisemitic Louis Farrakhan, not only argued that Israel was practicing apartheid; he also blamed Jews for South Africa’s racist regime.

Greenblatt led the Tufts protests against Muhammad, who described Jews as “bloodsuckers.” But he never suggested shutting down the event, nor questioned the rights of the Middle East Study Group to have used $10,000 in student activity funds to bring Muhammad to campus.

For Greenblatt then was not only a warrior against antisemitism, but also a champion of free speech. As editor of Observations, the opinion page of The Tufts Observer, he published wide-ranging viewpoints, including some he considered antisemitic.

“We believe that every group on campus has the right to invite whomever they feel will contribute to their education,” an Observer editorial stated, “More importantly, the groups who oppose the speaker can become informed about Muhammad’s ideology, and in so doing can learn how to combat what they despise.”

It seems like a sharp contrast with the Greenblatt of today, who has praised the president of Columbia University for calling in the New York Police Department to clear an encampment of pro-Palestinian protesters and arrest more than 100 students. Greenblatt recently called the student activists “campus proxies” of Iran, and on Monday suggested that the National Guard may be needed to ensure Jewish students’ safety on campus.

In the months since the Oct. 7 Hamas terror attack and the war it spawned, his ADL has also called on school administrators to investigate and ban anti-Zionist groups, sparking criticism from the American Civil Liberties Union.

“We had very intense debates when I was in college, but nobody got assaulted; nobody got spit on; nobody got followed to their dorm,” Greenblatt said when I asked him this week why his approach had changed.

“I spent Sunday afternoon at Columbia, and I heard firsthand from students who have been screamed at, harassed, and assaulted,” he continued. “At Harvard, at Brown and other places, what I’ve been told is that students feel physically, not intimidated, unsafe.”

He compared today’s campus situation to the deadly 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, and said of such protests, “I think time and place restrictions are smart and, unfortunately, sometimes necessary.”

‘Only through an open exchange of ideas’

Greenblatt, who grew up in Connecticut, attended Tufts from 1988 to 1992. He majored in English, was in the fraternity Sigma Phi Epsilon and spent four years working at The Observer, a weekly, as a reporter, copy editor, opinion editor and columnist.

During his sophomore year, the university made national news when students protested the president’s attempt to establish “free speech zones.”

The controversy started after a student sold misogynistic T-shirts that listed 15 reasons “Why Beer is Better than Women at Tufts.” In response, university administrators prohibited offensive expression in dorms and classrooms. The policy was rejected by the students it was meant to protect.

Greenblatt was The Observer opinion editor then, and Neil Swidey its editor-in-chief.

“As student journalists, we covered the story aggressively, from every angle,” said Swidey, now director of the journalism program at Brandeis University. “And our editorial page lined up against the university’s well-intentioned but highly problematic plan.”

Swidey sent me a PDF of the Observer editorial page from after the rule was suspended: “Any policy curtailing free speech would do no more than drive prejudice underground, where it cannot be exposed, criticized, or changed,” wrote the editorial board, which included Greenblatt.

In an earlier editorial opposing the rule, they’d written: “Only through an open exchange of ideas without fear of rebuke can students feel completely comfortable with being honest, learn from each other’s mistakes, and prepare themselves for the real, unsheltered world.”

The episode has stuck with Swidey, who is also editor-at-large of the Boston Globe Magazine. “I recognize that campus debates around free speech can be both challenging and highly charged,” he told me in an email, then quoted the late Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who said the remedy to harmful speech is “more speech, not enforced silence.”

‘Even stuff you find really distasteful’

As opinion editor, Greenblatt was the steward of those free-speech principles, and his section published a wide range of viewpoints, including ones he found offensive. Students were divided on the first Gulf War; campus conservatives railed against political correctness; and much space was devoted to the perennial debate around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“When I was an editor on the op-ed page, it really gave me an opportunity to wrestle with big ideas,” Greenblatt told me in our interview. “I learned firsthand about what it was like to accommodate all points of view, even those you don’t agree with, to allow everyone to have their say. Even stuff that you find really distasteful.”

Indeed, Greenblatt reprinted a New York Times op-ed by Edward Said, a Columbia University professor who was among Israel’s harshest critics. (Said died in 2003.) On the same page, Greenblatt ran an anti-Zionist student essay that compared Israel to apartheid South Africa and called Israel a ”cruel regime” that “violates every democratic principle.”

A few weeks later, a letter to the editor argued that the ethnic cleansing of Arabs was part of the Zionist project.

Greenblatt himself had more than two dozen bylined opinion columns. He defined himself as a “progressive”; wrote triumphantly after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison; and invoked his grandfather’s escape from the Holocaust in support of Haitian refugees.

He also wrote about the benefits of fraternities, his love of the hip-hop group RUN-DMC and his hatred of cheese.

“I don’t like cheese,” he said when we spoke this week. “I still don’t.”

In January 1990, Greenblatt, a hip-hop fan, accused the rap group Public Enemy of antisemitism for supporting Farrakhan, and for lyrics that blamed Jews for the death of Christ. He then published a defense of the group by a student who argued, “There is no plot by Public Enemy to get Jewish people.”

‘He mocked me’

When the Middle East Study Group invited Muhammad, the Nation of Islam leader, to campus in 1992, Greenblatt co-authored a resolution condemning Muhammad’s beliefs, which the Tufts student government passed 13 to 7. The resolution explicitly recognized the Black nationalist’s “right to appear and speak.”

In two columns about the event, Greenblatt did not call on his peers to boycott it. Instead, he urged students to challenge the speaker. “So attend the speech,” Greenblatt wrote, “and ask Khalid Abdul Muhammad.”

During the talk, Muhammad singled out Greenblatt, according to a newspaper account at the time, derisively calling him “Johnnie,” and claiming his article unjustly referred to Farrakhan as a Nazi sympathizer.

Greenblatt fired back during the Q&A, when Muhammad berated another student about his position on Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. “He’s not on trial, Senator McCarthy,” Greenblatt called out.

The day after Muhammad’s visit, Greenblatt’s publication wrote approvingly of the event, despite the shouting matches. Its only complaint was there were not enough seats for all who wanted to attend.

Greenblatt, now 53, remembered it vividly.

“He mocked me,” he said. “What I said back then, we should go and interrogate this guy and push him — that’s pretty much who I still am today.”

New rules for this moment?

Greenblatt, a tech and social entrepreneur who worked in the Obama administration before taking the helm at ADL a decade ago, said he still thinks students should confront and interrogate ideas they disagree with. “It’s the only way, especially in the college environment, you can grow,” he said.

But he said that anti-Zionists don’t engage in dialogue; they shut it down. And he said free speech does not mean all ideas should be platformed. “A smart campus newspaper editor,” he explained, “they have a responsibility to weed out what’s extreme.”

For Greenblatt, that includes most, if not all, anti-Zionism.

In 2022, he sparked controversy when he explicitly stated, “Anti-Zionism is antisemitism,” signaling that the ADL now saw pro-Palestinian activism on par with right-wing extremism. He had made a similar argument three decades earlier in an Observer piece headlined “Is Anti-Zionism the True Racism?”

“The basic philosophical tenet of the right of a nation of people to self-determination is not Jewish,” the article says.

“Rather, it is natural and apolitical, it is secular and humanist, it is democratic and egalitarian. This belief represents the foundation for independence movements across the world.”

Whether anti-Zionism is always antisemitism is a fraught subject of continual debate with big consequences. Those who think that is so, see Gaza solidarity encampments on Columbia and other campuses as, inherently, a form of Jewish harassment. Others say the encampments are clearly not inherently antisemitic, noting the large presence of Jews among their organizers, but acknowledge that individual protesters who threaten violence cross the line.

In a recent editorial, the Columbia Daily Spectator accused Minouche Shafik, the university president who brought in the police to break up the encampment, of “conflating pro-Palestinian campus activism with antisemitism.”

Greenblatt’s ADL has, since Oct. 7, expanded its criteria for counting antisemitic incidents to include rallies with “anti-Zionist chants and slogans.” Shortly before this latest outbreak of campus protests and police crackdowns, the organization issued campus antisemitism report cards: Columbia got a “D,” Tufts an “F.”

Today, Greenblatt told me, with antisemitism spiking, we need different rules than when he was in college. “Anti-Zionism is problematic,” he said, “particularly in this moment.”