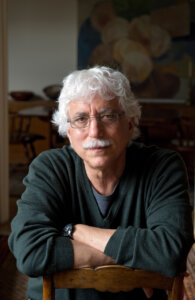

I was arrested protesting at Columbia in ’68. Today’s student encampments carry on a proud, brave tradition

Like the Vietnam War was nearly six decades ago, to many students, Israel’s assault on Gaza feels deeply personal

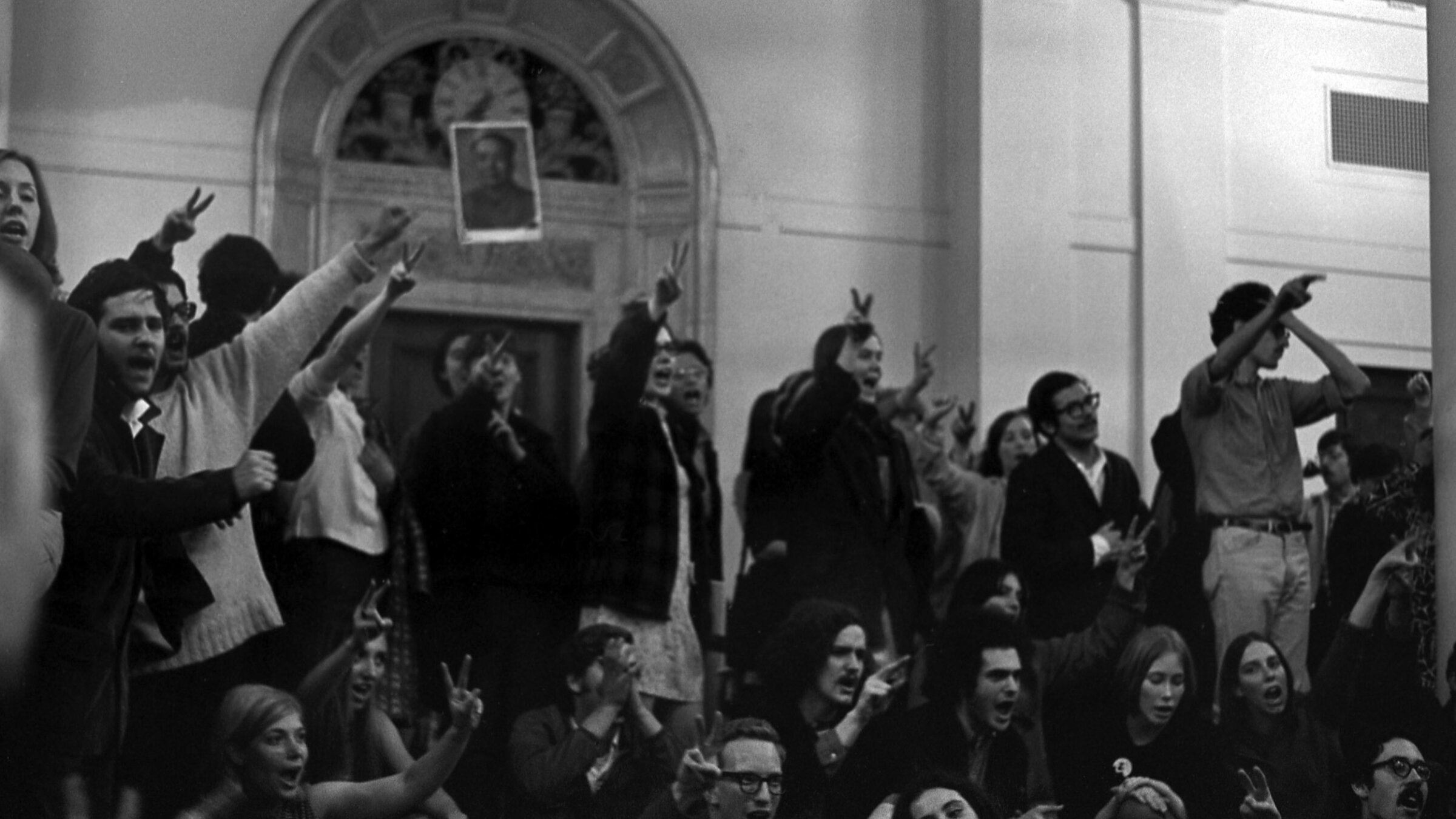

Students participate in the occupation of several buildings on Columbia University’s campus in 1968. Photo by Bev Grant/Getty Images

The Columbia campus was locked when I went to teach a class at the journalism school this February, with uniformed guards checking ID’s and police standing by. The by-then regular procedure was invoked whenever a demonstration against the Israeli war in Gaza was expected, but it was the first time I’d directly experienced it. It wouldn’t be the last.

Seeing what was clearly already an extreme response to student speech — long before Columbia’s president, Nemat Shafik, called in police to arrest nonviolent protesters last week — I couldn’t help but cast my mind back to another time, when I was an undergraduate at Columbia College.

Almost exactly 56 years ago, in 1968, I was engaged in the occupation of one of five buildings on campus with hundreds of my fellow Columbia University students. I was helping to occupy the Mathematics Building, known as the home of the strikers with the strongest convictions. We wanted Columbia to cease its research into weapons for the war in Vietnam, a war that had already killed more than a million Vietnamese and tens of thousands of Americans, and was tearing out the heart of our country. And we were dedicated to stopping Columbia from building a new gym in Morningside Park, which would make the only park in South Harlem effectively useless for its residents.

The administration, which had failed for years to listen to our peaceful protests, eventually called the police to drive us, many bleeding, out of our buildings one awful night. They made more than 700 arrests. I was one of them.

And yet, in the end, we won. By the fall semester, all of our demands were met.

There are differences between then and now. Our demonstrations posed a much greater challenge to the university’s normal operations: The ensuing unrest blew the roof off the campus, effectively stopping the regular functioning of the university for the rest of the spring. Today, the students have set up tent encampments on the lawns of the campus, out of the walkways, impeding nothing. We were proudly militant, they are proudly non-violent.

Yet there are many similarities between us.

A distant war, made personal

The Gaza war is characterized by killing at a massive, almost industrial scale, as was Vietnam before it. Both led to an explosion of anger around longstanding issues of race and colonialism, and set a fire in the hearts of young people. And while most students at American universities are not at risk of being roped into war — as many of us were, with the draft looming over us in ’68 — for many, the war in Gaza hits home in personal and sometimes unexpected ways.

Across the country, the pro-Palestinian demonstrations are full of Jewish students. On the first night of Passover, Jewish pro-Palestinian demonstrators held a Seder at the tents on Columbia’s South Lawn. Young people who grew up learning of Israel as a democratic and peace-loving haven for Jews now see hypocrisy in that image, held against the treatment of Palestinians in Gaza and the occupied West Bank. The horrifying death of more than an estimated 34,000 people in Gaza during Israel’s assault has turned that transformation of perspective into a profound drive to protest.

Working together in ’68, as we built our almost six-day-long society in our “communes” — named after the Paris Commune of 1871 — the ’68 protesters lived out a vision of what a fully cooperative, non-alienated community might be. We slept on hard floors and ate food contributed by the neighborhood, held endless meetings, and grew to love one another. The demonstrators on today’s campuses are doing the same. They are learning to live together, the competitive academic culture falling away in the heat of collective struggle for higher ends. They are held together by their common cause, their bravery and their sacrifice.

Both then and now, the university administration has leaned on procedural regulations, such as limiting where demonstrations are allowed to take place, to repress student groups and discipline leaders it wants to silence for political reasons. Students for Justice in Palestine and Jewish Voice for Peace were embargoed last October, as if Shafik and her advisors were reading from the disgraced playbook of Grayson Kirk, the former Columbia president who called in the NYPD on me and my peers. The administration has since kept applying discipline, without recognizing the legitimacy of the issues raised by the students, and without negotiating or treating them as reasonable adversaries.

Growing divisions — and solidarity

It should have been no surprise that the unlistened-to students of our current era reacted like those in ’68, by slowly escalating their protests. But it’s a surprise that, in nearly six decades, the administration hasn’t learned that calling in the cops doesn’t quell protests; it helps them take on a brilliant life of their own.

Now, as it was in our day, the campus is divided. Critics of our movement used buzzwords, like “communists,” “anarchists” and “hippies,” to reduce us protesters to enemies to be feared and dismissed. They tried to obscure the demands we made on a blameworthy institution.

Today, charges of “antisemitism” and students “feeling unsafe” are used in an attempt to cloud real issues and grievances.

At first the university was split, for and against us. Only the brutality of the NYPD as it cleared the campus exposed the sclerotic authority of the administration that called them in. Then, as now, that action prompted a wave of new solidarity. In ’68, Columbia students rallied together around our cause; today, encampments inspired by Columbia have sprung up around the country.

Name-calling as a repressive tactic

The criticism of today’s protest movement is more complicated than that in 1968. Allegations of antisemitism, in particular, carry even more baggage than the specter of communism, in part because of the visceral emotional reaction they can spark in Jews: Even a vibration of antisemitism, real or imputed, can lead to immediate fear. And it’s true that in several videos making the rounds online, random partisans in the streets outside Columbia can be seen using anti-Jewish insults. Yet there have been vanishingly few real examples of on-campus antisemitism at Columbia that originated from demonstrators.

That doesn’t make the fears some Jewish students feel less real. But it does call into question their validity. This situation demands the question: Why should we guarantee an academic culture with no challenges to long-held beliefs, for instance, that the State of Israel and being Jewish are synonymous?

This tension brings into question the narrative that various officials have spun around those fears. The demonstrations, the public is told, have been beset by antisemitic threats and rhetoric. From the first days of the protests, media stories across the country led with that assumption. Wealthy university funders have withdrawn contributions. Speaker of the House Mike Johnson and his cohort descended on the campus to command the cameras while masses of students, who refute his claims, are pictured as a faceless mob. (Other politicians, like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, have visited not to grandstand, but to get to actually know the protesters now shaping our national discourse.)

Both now and in ’68, attacks of name-calling seek to stop the public from taking the protests seriously. The cries of antisemitism have been militarized by those speaking about them on national television. It is the old red-baiting pattern that uses a fear-producing buzz-word as a smokescreen to obscure real issues and justified protests.

Now, here we are. Rejecting officials’ condemnation, the student protests have spread like a storm across the United States and around the world. Just like in 1968, Columbia University has become the seed of a vast outpouring of student feeling that gives voice to an even more vast sentiment among the youth that a terrible injustice must be redressed. In our day, our protests hastened the end of the Vietnam War and continued to raise the issue of racism. We will see if these students also help to change the world that they have inherited.