He was a Jewish hostage in Iran. Now he’s advocating for captives in Gaza

Barry Rosen opens up about Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli captives and his 444 days of darkness

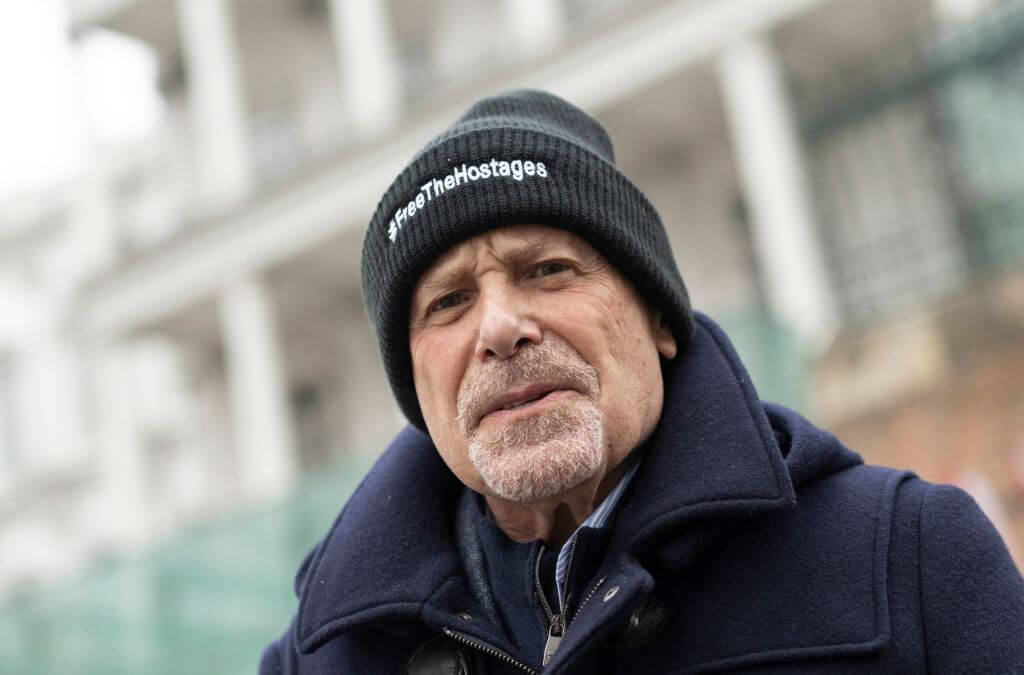

Barry Rosen, a former hostage in Iran, at a Friday night service at American Mensa’s annual gathering in Kansas City in July 2024. Photo by Benyamin Cohen

Benyamin Cohen spent 48 hours at American Mensa’s annual gathering, where he spoke about his book, The Einstein Effect, moderated two panel discussions and mingled with people way smarter than him.

KANSAS CITY, Missouri — The Friday night service at American Mensa’s annual gathering included 24 Jews and a Mormon. Among the people at the smartest minyan in the United States were a computer coder, a bioethicist, and one who serves as an ambassador for Jews for the Preservation of Gun Ownership. He has an IQ of 182 and looks like Yosemite Sam.

Amidst the makeshift congregation, such as it was, in a nondescript hotel conference room was Barry Rosen, a man who spent 444 days as a hostage in Iran during the final year of Jimmy Carter’s presidency.

As he rose from his chair to recite the Amidah, the central section of every Jewish prayer service, Rosen paused and smiled at one particular line. “This phrase, matir asurim, freeing the captives,” he said pointing to a line in Hebrew in the prayer booklet, “has always resonated with me.”

Rosen, 80, has spent the past four decades advocating for hostages all over the world — a calling not chosen, but embraced. That mission has intensified in the months since Oct. 7, when Hamas attacked Israel and took hundreds of people captive.

He brought Israeli hostage families to meet with The New York Times’ editorial board in an effort to humanize their stories. He met in Brussels this month with Shoshan Haran, an Israeli who was released by Hamas after 50 days in captivity, to advocate for hostage diplomacy at a meeting of officials at the European Union.

“It’s part and parcel of my DNA that I’m going to be there for hostages as long as I possibly can be,” Rosen told me.

He has led Zoom calls, telling whoever will listen what daily life is like for a hostage. “I was in darkness,” he said, both literally and figuratively. During his entire 14 months as a hostage, he spent only 20 minutes outside. He wore the same pair of pants for 150 days. “I was treated very badly, beaten up, threatened with automatic weapons held to my head,” he told me, recalling the story he’s told so many times before and in his memoir, The Destined Hour. “You’re just a piece of meat.”

One ray of hope for Rosen came in the form of a small bird. He did not have a window in his cell, but there was a vent through which he could see the bird’s reflection. “That bird was my saving grace,” he said. “He became my friend.”

A love for the Iranian people

Barry Rosen would be the first to admit that he is not a genius. He was at this Mensa convention as an invited speaker. Guests at previous Mensa conventions included Harpo Marx’s son and Boris Karloff’s daughter, and the last surviving navigator of the Enola Gay.

“I didn’t even know these things existed,” he told me when I first met up with him in the bright and airy lobby of the Sheraton Crown Center in downtown Kansas City, across the street from the worldwide headquarters of Hallmark.

We walked past a hotel ballroom filled with hundreds of people working on jigsaw puzzles, turned left at the pun competition, and ignored the women dressed as Mrs. Roper from Three’s Company.

We settled into a massive convention hall that had been converted into a 24-hour cafeteria for the 1,200 Mensans. Rosen grabbed two oatmeal raisin granola bars and wolfed them down before we arrived at a table to sit.

Granola bars, bowls of M&Ms, freezers full of ice cream — these snacks here were not readily available to Rosen while he was a prisoner of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Rosen endured mock executions, was starved and used as a political pawn. Those months as a hostage have defined all that has come after it.

In Jan. 2022, for instance, Rosen traveled to Vienna where the U.S. was holding indirect talks with Iran about reviving the 2015 nuclear deal. As a senior advisor for United Against Nuclear Iran, Rosen was there to voice his concerns that the country was still holding at least a dozen foreign nationals in prison and using them as bargaining chips.

He parked himself on the street corner outside the hotel where the talks were taking place and went on a hunger strike to draw worldwide attention.

Rosen told me the irony is that, to this day, he loves Iran and its people. As a young man, he volunteered with the Peace Corps, and was later excited to work at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. He spoke fluent Farsi and fell in love with the culture. A local Jewish family took him in as their own, offering a home away from home.

But any semblance of home was forever changed early on the morning of November 4, 1979, when he and 51 others were taken hostage.

As with the current crisis in Gaza, family members were thrust into the spotlight. Rosen’s wife, Barbara, became a national figure — giving television interviews, working with politicians, meeting with Pope John Paul II — always reminding people that their loved ones were still trapped.

Netanyahu’s speech to Congress

Rosen thinks it is important for the Israeli families to keep up their public protests when they feel betrayed by what they see as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s obstinance. “Netanyahu has lost any legitimacy in my mind to represent the state of Israel, in this very critical time in history,” Rosen said. “I find him a dangerous person.”

Rosen was invited to the July 24 memorial service for the late Sen. Joseph Lieberman, where Netanyahu delivered remarks. In one section of the synagogue, the Washington Hebrew Congregation, were placards featuring the hostages who are still being held in Gaza. “I walked over,” Rosen recalled, “and spent time just looking at the faces of the people who I have more in common with than Netanyahu.”

As Rosen drove home after the service, he flipped on the radio to hear the Israeli prime minister’s record fourth address to Congress. A big focus of the speech was on Iran’s role in funding Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack and, more broadly, painting Iran as a common enemy of both Israel and the U.S. Netanyahu even mentioned how Rosen and his fellow hostages were held captive for 444 days.

“If he had mentioned that his priority was to free the hostages immediately,” Rosen said, “then I just might have felt he was truly speaking to me.”

Some Israeli soldiers, relatives of those captured by Hamas and a freed hostage joined Netanyahu inside the Capitol, where they received standing ovations. Other hostage family members protested outside, and some were arrested.

“Everything Netanyahu said was factually correct,” Rosen told me afterwards. “But, context is important, too. I don’t disagree at all that Iran is the most dangerous actor vis-à-vis Israel and in vast parts of the Arab world. But the U.S. played an important role in making that happen — whether kowtowing to the Shah, backing Saddam in the eight year war with Iran, and giving Iran the opportunity to make Iraq a Shia stronghold beholden to the Islamic Republic.”

Rosen worries that of the roughly 120 remaining hostages in Gaza, many will not make it home. “I think that it’s diminishing returns, the longer they’re held,” he said in a thoughtful, almost methodical manner, belying his decades as a diplomat.

I asked him what the hostages must be thinking, hearing bits and pieces of news of an impending deal, only to find out it has broken down time after time. “You’re sitting in the same place weeks on end, months on end. And you don’t really know if anything is happening or not,” Rosen said. “Whenever you think something might happen and it doesn’t happen, it works against you,” he said. “That’s how I felt.”

The abuse — both emotionally and physically — still weighs on Rosen, who has been married for 52 years and has two children and five grandchildren. “I fall prey to what goes on in terms of my own psychological makeup,” he said.

“There are moments where I just wake up and feel a sense of imprisonment, a lack of optimism. I know I’m in that mood. I know I’m there. The captivity of it all is just glued to my soul.”

‘Bewildered’ by campus protests

Israel’s war in Gaza strikes differently for someone like Rosen, a Jew and former hostage.

“All I want is peace in the area,” he said. “But I do think that Oct. 7 was such a vicious, horrible day, totally unnecessary in the sense of how people were treated that I can also understand very well the Israeli reaction to their loved ones.”

“I feel a sense of tremendous empathy and love for the Israelis. And, at the same time, I’m regretful that there are casual casualties on the Palestinian side that are very heavy and cause much pain to their families and to all of us, too. I don’t know if it calls for all the deaths and murders of people on the other side, who are really living terrible lives now.”

Rosen said he was “bewildered” and “taken aback” by the vitriol on college campuses this spring. “I didn’t really understand the heavy reaction against the state of Israel,” said Rosen, who is a graduate of Columbia University and, after he was released from captivity, taught a course on the Iranian revolution at Brooklyn College.

“I think to a large degree, many of the students see Israel as the oppressors of the Palestinian people. And whether they’ve read enough or not, they’ve expressed that feeling. It does have an ever-present feeling of discomfort.”

Back at the Mensa minyan, in a room full of geniuses, Rosen shared a story. While he and the other hostages were in captivity, they received care packages from the U.S. that included letters (often with lines blacked out by the guards) and supplies to celebrate Christmas and Thanksgiving. One concerned rabbi sent a menorah to Rosen, who spent his formative years in a Brooklyn yeshiva. The guards let him light it so he could celebrate Hanukkah with his cell mates, none of whom were Jewish.

The Friday night service came to a close with a collective recitation of the Mourner’s Kaddish, which concludes with the call for God to “create peace for us and for all Israel.” Rosen closed his eyes, swayed back and forth, and prayed.