He’s writing Kamala Harris’ DNC speech. He also wrote a book on Holocaust survivors

Adam Frankel, whose grandparents survived the Nazis, is lead writer for Harris’ acceptance speech

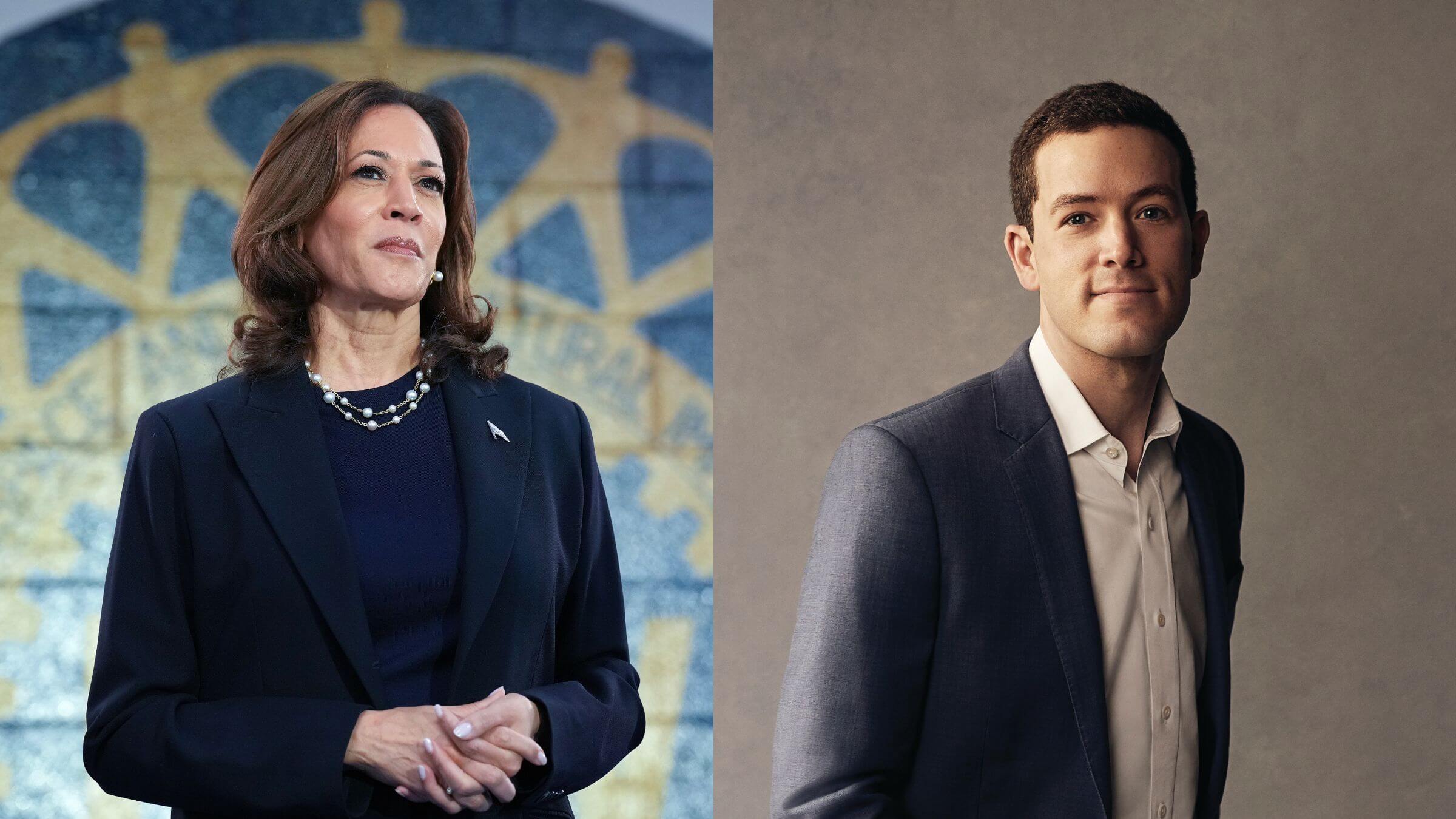

Kamala Harris, left; her speechwriter, Adam Frankel, right. Photo by Andrew Harnik/Getty (Harris); HarperCollins (Frankel)

The man writing Kamala Harris’ acceptance speech is the grandson of Holocaust survivors and the author of a book about what he calls “intergenerational trauma.”

Adam Frankel is the lead writer on the speech Kamala Harris will give Thursday night at the Democratic National Convention, when she is expected to accept the party’s nomination for president, according to The New York Times.

Frankel, 43, was previously a speechwriter for former President Barack Obama. Since 2021, he has served as an adviser to Harris in the vice president’s office.

His maternal grandfather survived Dachau and other concentration camps. His maternal grandmother got through the war hiding in a forest in Eastern Europe with Jewish resistance fighters.

In 2019, Frankel published The Survivors: A Story of War, Inheritance, and Healing about their ordeals and how that impacted their family across generations. His mother struggled with mental health issues, and when he was 25, she told him that the man he believed was his father was not his biological dad. That turned out to be just one of many family secrets.

Frankel referred a request for an interview to Harris’ office; Harris’ office did not respond.

A houseful of ghosts

Frankel was raised by his mother after her divorce from the man he believed to be his father. But he spent a lot of time with his grandparents in a community of survivors in New Haven, Connecticut. They didn’t talk much about what they’d endured during the war, but his grandmother had nightmares and the house seemed to be full of ghosts.

“The Holocaust hovered over my childhood,” Frankel told The Times of Israel. “My mother and I lived in Munich for a few months when I was young and she took me on a trip to Dachau. As a young kid we bought a book about Dachau and I would always look at the pictures. I spent a lot of time thinking about this stuff.”

Frankel’s mother — named, like her three siblings, for relatives who were murdered in Europe — was prone to depression and rage, and at one point tried to kill herself. “Forgive her,” his grandfather told Frankel. The need for forgiveness became clearer once the affair that led to his birth was revealed.

Another family secret was that his grandparents, who met in a displaced persons camp, had changed their names from Gershon Gubersky and Rivke Wexler to Abraham and Lea Perecman. They did it to cover up Gubersky’s connection to a black-market operation, fearing that the case might harm their chances of emigration and eligibility for reparations. Those false identities became part of the family culture of lies and things that could not be spoken of.

Political connections: Minow, Psaki, Favreau, JFK

Frankel is a Fulbright scholar and alumnus of Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School and the London School of Economics. He’s well-connected politically: His sister-in-law, Jen Psaki, was former White House press secretary for President Joe Biden; his wife, Stephanie Psaki, is a senior adviser on human rights and gender equity at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

His paternal grandfather was a Democratic speechwriter and activist. His great-uncle, Newt Minow, chaired the Federal Communications Commission under President John F. Kennedy. Minow hired Obama as a summer associate at his Chicago law firm on the recommendation of his daughter, Harvard Law dean Martha Minow (Frankel’s cousin), who’d had Obama as a student.

Obama “would repay the favor years later,” hiring Frankel to his team, as a Forward story about his book put it. Frankel himself said he was hired to Obama’s campaign by a friend, Jon Favreau, who was Obama’s speechwriting director.

After leaving the Obama White House, Frankel ran a national education nonprofit, Digital Promise, and later was vice president of communications at PepsiCo and at Antora Energy, a Bill Gates-backed company. He also helped JFK’s speechwriter, Ted Sorensen, with a memoir.

Can trauma be inherited?

Frankel’s book isn’t just about his own family history. He also tackles a larger issue: how trauma is experienced across generations and whether it can be inherited, not just through the psychological impact, but physically and genetically.

“There’s fascinating research on the way that trauma can leave an imprint on DNA,” he told MSNBC in an interview. He said writing the book helped him understand the way his grandparents’ trauma “had reverberated to my mom and her siblings” and therefore helped him “understand the family’s larger stories.”

He also said he hopes his story has broader meaning for others. “In my family, it’s war trauma and mental health issues,” he told MSNBC. “In other families, it’s addiction, abuse, racism, all kinds of trauma that affects us in all kinds of ways. My hope is if we can understand that and understand the way trauma can reverberate across the generations, we can all process it and move beyond it a little more easily.”

In an interview with a Princeton alumni publication, Frankel raised themes that seem as relevant to Harris’ campaign and Jewish concerns now as they were when he made the comments in 2019. He said his family story shows why it’s essential to be “mindful” of “not just of the nationalism and racial-purity ideas that contributed to the Holocaust, but just the dangers, more broadly, of fascism, the imperative of being vigilant about democracy.”