‘It never goes away’: A former hostage describes the paradox of freedom for Israelis who returned home from Gaza

Barry Rosen, a survivor of the Iran hostage crisis, reflects on life as a free man decades after his captivity

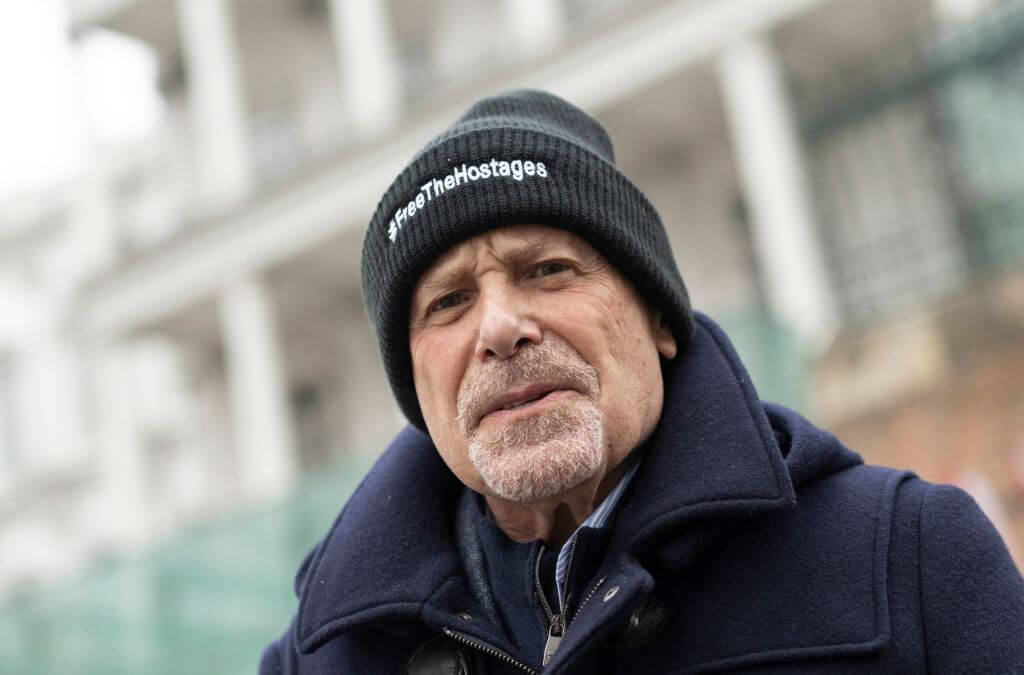

Barry Rosen, who was held hostage in Iran during 444 days from 1979 to 1981, in Vienna in 2022. Photo by JOE KLAMAR/AFP via Getty Images

Barry Rosen knows what it means to wait for freedom.

He spent 444 days as a hostage, one of 52 Americans held prisoner at the U.S. embassy in Iran from 1979 to 1981. He described when he was reunited with his family as “one of the greatest moments” of his life.

But Rosen also knows from experience that the psychological scars of captivity endure long after that celebratory moment.

So when he heard that the remaining living hostages held by Hamas in Gaza were being released this week, he felt “overwhelmingly relieved.” But his joy was also tempered by worries of what comes next, and the memory of the difficulties he faced re-entering society after being stripped of freedom for so long.

“It never goes away,” said Rosen, now 81. “Being a hostage is part of my DNA.”

444 days of darkness

Rosen, who is Jewish and grew up in Brooklyn, fell in love with Iranian culture during his time as a Peace Corps officer there. A decade later, he returned to work as a press attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran.

On November 4, 1979, he was sitting in the embassy office when men with clubs stormed in and accused him of spying for the U.S. government.

Over the next nearly year and a half, he endured brutal conditions: Rosen was kept in a cell with no windows, subjected to mock executions, starved, and beaten, he said. He often feared he would never be released, telling his prison guards he expected them to grow old together.

Small reminders of the outside world helped him. The singular time his captors allowed him outside for 15 minutes, he slipped a blade of grass into his pocket — and would think of the baseball games he attended with his father as a young boy whenever he took it out.

Meanwhile, Rosen’s wife, Barbara, became a national figure, speaking to the media and meeting with politicians to advocate for his release.

President Jimmy Carter ultimately brokered a deal. After 444 days in captivity, Rosen was blindfolded and driven to the airport in Tehran. Soon after, he was in his family’s arms.

They popped champagne, he said, and “drank as much as they possibly could.”

The road to recovery

After the initial elation of being freed, Rosen said it took several months before he was able to resume a semblance of normal life.

Following his release, he went on a speaking tour and co-wrote a book with his wife, The Destined Hour: The Hostage Crisis and One Family’s Ordeal. Writing about his experience, he said, helped him process what had occurred.

Rosen also channeled the trauma into advocacy for other hostages. He co-founded Hostage Aid Worldwide, which researches unlawful detention and maintains a database of hostages around the world. In 2022, he went on a hunger strike to raise awareness of the plight of foreign nationals held by Iran. Most recently, he turned his attention to the hostages in Gaza, helping to schedule meetings between hostage families and officials at the United Nations.

Rosen said he feels a “certain camaraderie” with the hostages returning to Israel from Gaza, many of whom were confined to underground tunnels in darkness.

“The human condition is similar when you’re held under a gun or tied up, not knowing whether you will live or die,” he said.

He emphasized that some returning hostages may not be ready to speak about their experiences and stressed the importance of respecting how different people may process trauma.

Even small choices, like deciding what to eat, can bring up emotions for returning hostages.

“You’re being held for so long without any power over anything,” Rosen said. “If you’re now given a choice to do this or do that, it could be very difficult.”

On his speaking tours, Rosen said it was often challenging to translate the experience of being a hostage to an audience. When asked, “How does it feel to be a hostage?” he would reply that the experience was too complex to describe.

“I don’t particularly think that most people want to hear the pain,” Rosen said. “It’s something that cannot really be conveyed to another person, even if you’re the most articulate person in the world.”