Why Josh Shapiro’s memoir could complicate a presidential run

From the Tree of Life massacre to his 2024 vetting, the Pennsylvania governor frames his public life through moments tied to Jewish identity

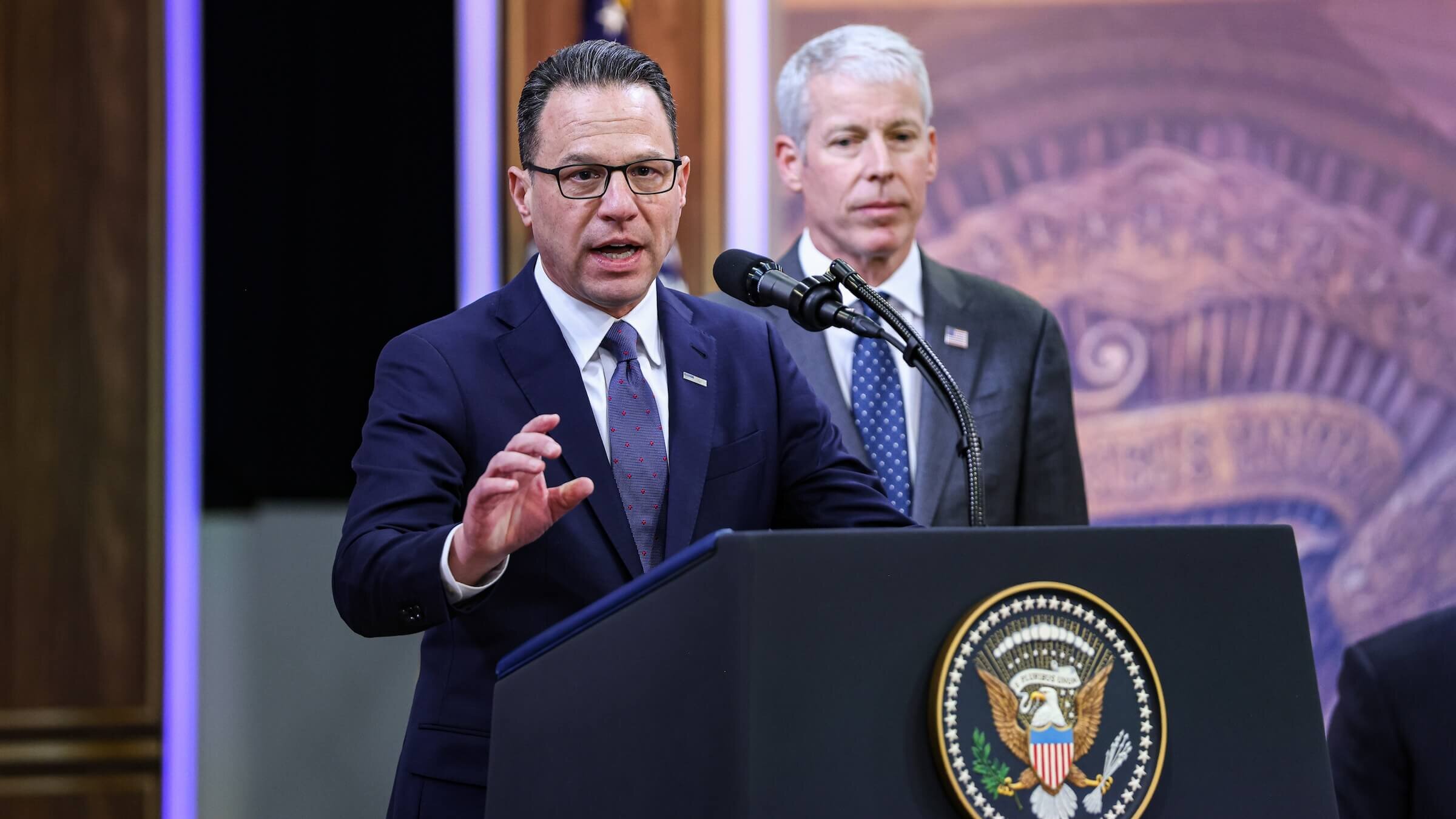

Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro at the White House on Jan. 16. Photo by Valerie Plesch/Bloomberg

When politicians publish memoirs, the goal is usually clear: introduce themselves to voters beyond their home state, often ahead of an expected national run, and present the version of their story that makes them most appealing to the broadest base. That’s what makes Josh Shapiro’s new memoir potentially counterintuitive.

In Where We Keep the Light, set to be published on Tuesday and obtained by the Forward, Pennsylvania’s Jewish governor does not sidestep the parts of his biography and political record that could complicate a 2028 presidential bid.

Instead, he leans into them. Most notably, in a passage that made headlines earlier this week, Shapiro reveals that during his vetting as a potential vice presidential nominee in 2024, he was questioned so aggressively about Israel — including being asked whether he had ever been an Israeli agent — that he felt singled out because he is Jewish.

Shapiro, who has been mentioned as a potential first Jewish president since his gubernatorial campaign in 2022, was one of six finalists who conducted interviews with the campaign of then-Vice President Kamala Harris, a group that included Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker, who is also Jewish. Shapiro’s popularity as a governor from a key battleground state, strong oratory skills and reputation as a moderate made him a formidable choice for many Democrats.

But Shapiro’s staunch defense of Israel and criticism of the pro-Palestinian protests after the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attacks made him a more complicated choice at a moment of deep polarization within the Democratic Party. Shapiro refused to call for a unilateral ceasefire in Gaza, he highlighted expressions of antisemitism at pro-Palestinian protests, and he criticized a “culture” at the University of Pennsylvania which he said did not take antisemitism seriously enough.

In his interview with Harris before she ultimately selected Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz as her running mate, Shapiro writes that he was urged to apologize for some of his comments about the protests to avoid alienating younger, more progressive voters and the Muslim electorate in Michigan. “‘No,’ I said flatly,” Shapiro writes.

Embracing a position that could complicate a campaign rather than smoothing away rough edges is not without precedent. In New York City, Mayor Zohran Mamdani sustained criticism during his campaign for his refusal to soften his stance on Israel, which alienated Jewish voters, long considered one of the most influential blocs in citywide races. But he defied expectations, scoring a surprise primary victory in a city with the largest Jewish community outside Israel and winning the mayoralty with a majority of the vote.

But Mamdani’s political focus was local, driven by social media and grassroots organizing, and the response was immediate, not years away. His stance on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict actually attracted new voters.

For Shapiro, the stakes are national and long-term — and the benefits are far less certain. Palestinian rights and the Gaza war have increasingly become a litmus test for Democrats, many of whom want sharper opposition to Israel. Polls show that Democratic voters are increasingly sympathetic to Palestinians. Even national Jewish Democrats, like Pritzker and former Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel — both considered possible presidential candidates in 2028 — have publicly challenged Israeli policy. In July, a record 27 Senate Democrats, a majority of the caucus, supported a pair of resolutions calling for the blocking of weapons transfers to Israel. Shapiro has repeatedly been critical of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and, last year, criticized the Israeli government’s rejection of international hunger reports in Gaza, calling it “abhorrent” and “wrong.”

“People have grown frustrated with some of their elected leaders who just blow with the wind and take a poll instead of finding their pulse,” Shapiro writes. “I try to stay true to what I believe is right regardless of what others think.”

In the book, Shapiro focuses on humanizing moments, detailing experiences shaped by and tied closely to his Jewish identity.

Passover arson attack

The book opens with a harrowing account of the Passover arson attack on the Pennsylvania governor’s residence, hours after his family’s Seder, by an intruder who said he wanted to beat the governor with a sledgehammer over what he claimed was a lack of empathy towards Palestinians.

Shapiro recounts how the attack rattled his children and sharpened his sense that antisemitic violence is a lived reality — even for a governor with a police detail. “I have hardly been shy about my beliefs and my faith, all of which have put a target on my back over the last half decade,” he writes. “The vitriol only intensified after the Oct. 7 attacks on Israel, as I continued to live my Judaism out loud.”

Still, he continues, until that moment, he felt safe. “The bubble burst that morning,” Shapiro writes. “People did want to kill me. They were hoping to, and willing to try.”

The Pennsylvania governor said this sentiment was shared by many American Jews who felt frightened after learning of the attack. But they were also comforted by his response and his refusal to be deterred from openly practicing his religion.

Tree of Life massacre

Shapiro devotes a chapter to the 2018 massacre at the Tree of Life Congregation in Pittsburgh that killed 11 people, describing his role as attorney general at the time and the emotional toll of repeatedly standing with a community shattered by the deadliest antisemitic attack in American history. Shapiro was sworn in as the state’s 48th governor on a stack of three Bibles, including one that was rescued from the synagogue.

The episode, he writes, reinforced his belief that political leadership must be rooted in moral clarity. “It has only made me more proud to be Jewish, more willing and able to use my voice and whatever platform I do have in my position to speak out.”

Shapiro faced criticism for switching his position on the death penalty, after initially favoring it for the killer, Robert Bowers. In the book, he defends his evolution on the issue, after meeting with some of the families of those slain in the shooting attack and a conversation with his son Max. “I went the opposite way of what would be politically popular for me,” he writes. “But it was a matter of principle for me, not politics. I wasn’t about playing a game or pleasing a constituency.”

Alliance with Barack Obama

The memoir also revisits an earlier chapter in Shapiro’s political life: his defense of former President Barack Obama during the 2008 campaign, when Obama faced skepticism in the Jewish community over his associations with Chicago pastor Jeremiah Wright and his positions on Israel. Shapiro’s oratory skills are often compared to Obama’s.

Shapiro, who was at the time a state representative, writes that he was criticized within his own community for vouching for Obama, who went on to win the White House. Shapiro said a private conversation with the then-candidate convinced him that Obama’s commitment to the Jewish community was genuine.

“I felt comfortable defending his beliefs,” Shapiro writes. “I thought the attacks were unfair.”

Shapiro recalls that Obama invited him to attend the first-ever Seder he hosted with several Jewish aides as he campaigned throughout the state during the Democratic primary. “I politely declined and explained I needed to be home with my family,” he writes. “He totally understood.” Obama went on to lose Pennsylvania to Hillary Clinton.

A semester in Israel

Shapiro also recounts his early relationship with Israel, including a trip he took as a teenager with his classmates from Akiba Hebrew Academy — around the time he met his wife Lori — and how those experiences shaped his views on the Jewish state.

Shapiro spent four months living in a dorm, taking classes and touring the country. Jerusalem, he writes, felt entirely different from home, where his faith had largely been contained within the walls of his synagogue on Saturday mornings or at the family table on Friday nights. Shapiro and his family are practicing Conservative Jews who keep kosher and gather for Shabbat dinners, joined by Shapiro’s parents and in-laws.

“There was something foundational about being in Israel that really connected me more to my faith,” he writes. “In Israel, it was just everywhere. It was the first time I could feel faith. I could see it and touch it, and it wasn’t abstract.”

On Saturday nights after Shabbat ended, he and his friends would wander Ben-Yehuda Street, watching crowds spill out of cafes and bars. Every time, he would run into someone with a connection to Pennsylvania or to his family. It was a reminder, he writes, of the bonds tying Jews together around the world.

Shapiro proposed to his wife in 1997 under the 19th-century Montefiore Windmill in the Yemin Moshe neighborhood of Jerusalem, during one of more than a dozen trips to Israel.

Vetting as vice president

The final chapter of the book recounts former President Joe Biden’s decision to step aside and Shapiro’s willingness to be considered as a vice presidential nominee. Shapiro writes that while he was publicly praised, there was also what he describes as a coordinated effort to derail his candidacy, including “ugly antisemitic rhetoric.” He recalls praying frequently during that period, hoping the process would go smoothly. “I said the Shema more times during that week than maybe I had in my whole life before,” he writes.

When he first met with the vetting team over Zoom, Shapiro says the panel “spent a lot of time asking me about Israel.” He began to wonder, he writes, “whether these questions were being posed to just me — the only Jewish guy in the running — or if everyone who had not held federal office was being grilled about Israel in the same way.”

Ahead of his consequential meeting with Vice President Kamala Harris at the Naval Observatory, Shapiro writes, members of the vetting team asked whether he had “ever been an agent of the Israeli government” or had “ever communicated with an undercover agent of Israel.” Early in his career, Shapiro briefly worked in the Israeli Embassy’s public affairs division in Washington. He says he told Dana Remus, a former White House counsel under Biden and a senior member of Harris’ vetting team, “how offensive the question was.”

The Gaza war loomed over the campaign even before Biden withdrew from the race. Anxious Democrats pressed Biden to take a tougher stance on Israel as a way to recover from his disastrous debate performance in June 2024. Some urged an arms embargo to appeal to disaffected progressives and Michigan voters who had cast “uncommitted” ballots in the primary. Harris took a more forceful public position in calling for an immediate ceasefire to address the humanitarian crisis.

According to Harris’ own memoir, 107 Days, in her private conversation with Shapiro, she discussed how his selection might affect the campaign, including the risk of protests tied to Gaza at the Democratic National Convention and “what effect it might have on the enthusiasm we were trying to build.” Harris wrote that Shapiro responded by saying he had clarified that earlier views he held were misguided and that he was firmly committed to a two-state solution.

Shapiro’s account of that exchange is very different. He writes that Harris pressed him to apologize for criticizing pro-Palestinian campus protests, which he refused to do. “There wasn’t much more issue-based conversation before we moved on to what the [role of] vice president would look like in her administration,” he writes.

After leaving that meeting, Shapiro writes he considered publicly withdrawing his name from consideration. Instead, he privately informed the Harris team that he no longer wanted the job. “I had prayed for clarity,” he writes. “And now I was nothing but clear.”

Shapiro’s memoir will be released on Jan. 27.