Even in Israel, Some Jews Reject Circumcision

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Circumcision is one of Judaism’s most important laws and for generations of faithful it has symbolised a Biblical covenant with God.

But in Israel, more and more Jewish parents are saying no to the blade.

“It’s such a taboo in Israel and in Judaism,” said Gali, nursing her six-week-old son, about the decision not to have him circumcised.

“It’s like coming out of the closet,” she said, asking to be identified by her first name only because she had not told her relatives yet.

Nearly all baby boys in Israel are circumcised. Be their parents ultra-Orthodox or totally secular Jews, it is by far the most common choice. Most Israeli-Arabs also keep with a practice that is widespread in the Muslim world.

Jewish circumcisions are done when the baby is eight days old. The majority are performed by a mohel, a religious man trained in the procedure carried out in a festive religious ceremony called a “brit”, Hebrew for covenant.

But an increasing minority fear it is a form of physical abuse.

“It’s the same as if someone would tell me ‘it’s our culture to cut off a finger when he is born’,” said Rakefet Kaufman, who also did not have her son circumcised.

“People should see it as abuse because it is done to a baby without asking him,” she said.

When Gali learnt she was carrying a baby boy it was obvious to her that he would be circumcised. But she started to think again after a conversation with a friend whose son was uncircumcised.

“She asked me what my reason was for doing it, was it religious? I said no. Was it for health reasons? No. Social? No. Then it began to sink in. I began to read more about it, enter Internet forums, I began to realise that I cannot do it.”

“The phenomenon is growing, I have no doubt,” said Ronit Tamir, who founded a support group for families who have chosen not to circumcise their sons.

“When we started the group 12 years ago we had to work hard to find 40 families … They were keeping it secret and we had to promise them we’d keep it secret,” she said. “Then, we’d get one or two phone calls a month. Nowadays I get dozens of emails and phone calls a month, hundreds a year.”

Tamir believes Jews in today’s Israel find it easier to break religious taboos.

“People are asking themselves what it means to be Jewish these days,” she said, and that leads some to question rules of all kinds, including circumcision.

In societies around the world who circumcise boys for non-religious reasons, out of habit or tradition or because of the perceived health benefits, the practice can be controversial.

Rates of circumcision in Europe are well under 20 percent, while in the United States, according to 2010 statistics cited by the Center for Disease Control (CDC), more than half of newborn boys continue to be circumcised.

The American Academy of Paediatrics said in August that the health benefits of infant circumcision – potentially avoiding infection, cancer and sexually-transmitted diseases – outweighed the risks, but said parents should make the final call.

But where the decision is ultimately a matter of personal choice for many families around the world, for Jews who question the tradition, it is more complicated.

“It is the covenant between us and God – a sign that one cannot deny and that Jews have kept even in times of persecution,” said one well-known mohel who has been performing circumcisions in Israel for more than 30 years. He asked not to be named to avoid being connected to any controversy.

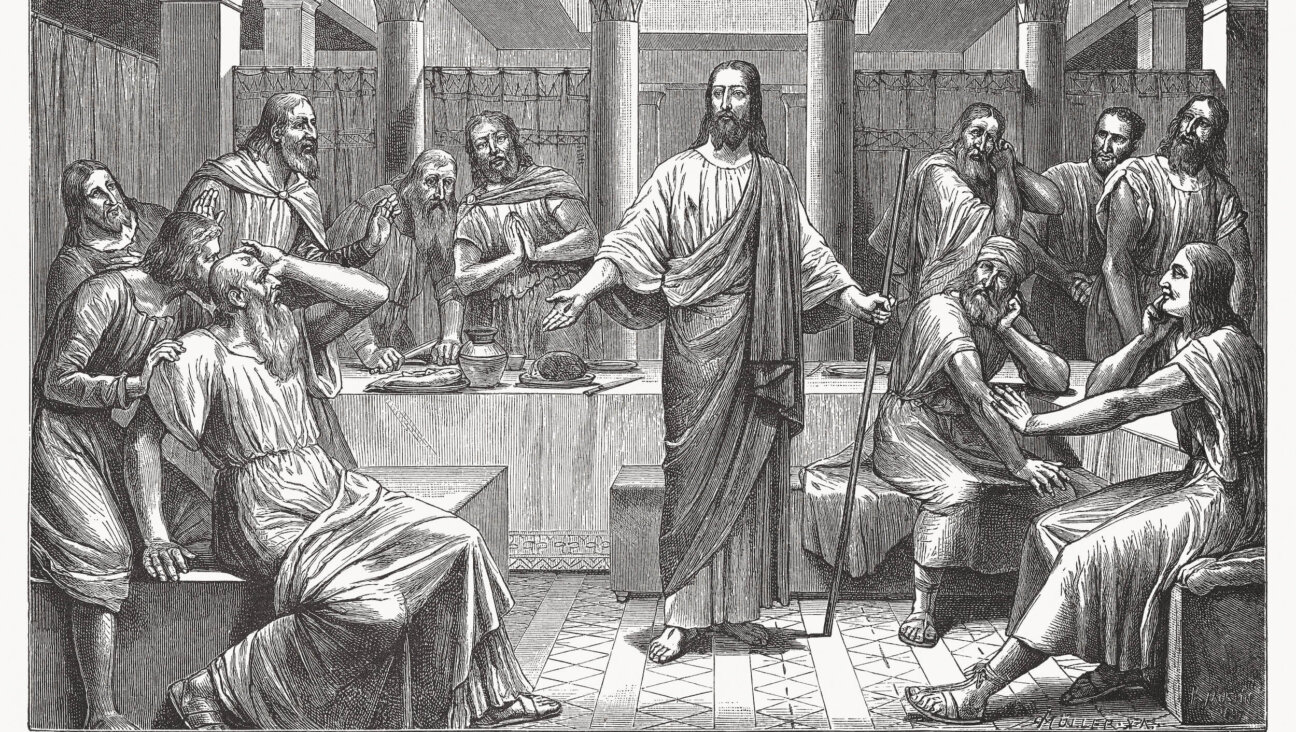

He pointed to the Book of Genesis, where God said to Abraham: “And you shall circumcise the flesh of your foreskins; and it shall be a sign of the covenant between me and you.”

It is this covenant that, the mohel said, that “keeps the people of Israel together”.

The Bible goes on: “And the uncircumcised male child whose flesh of his foreskin is not circumcised, that soul shall be cut off from his people; he has broken my covenant.”

Scholars have differed over the years what this means in practice.

BEING DIFFERENT

Tamir is unswayed by the ancient verses.

“This edict is painful, irreversible and maims,” she said. The Internet was helping to spread the word, she said, allowing parents to find information about circumcision and seek advice anonymously.

Some Jewish groups in the United States which oppose circumcision offer alternative religious brit ceremonies that do not include an actual circumcision.

“There is definitely a growing number of Jewish families in the U.S. who are choosing not to circumcise,” said Florida-based Rebecca Wald. In 2010 she started a website to connect parents who are unsure about what to do.

“Since then, in phone calls, emails, and on social networking sites I have connected with hundreds of Jewish people in the U.S. who question circumcision.” she said in an email interview. “Many of them have intact (uncircumcised) sons or plan to leave future sons intact.”

Wald’s son was not circumcised.

“I have a very strong sense of Jewish identity and, believe it or not, having an intact son has only deepened it,” she said.

In Israel, where the vast majority are circumcised, the dilemma may be particularly difficult.

Although she is confident of the choice she and her husband made, Gali still has one concern.

“The main issue which still troubles me a little is the social one, that one day he may come to me and say ‘Mom, why did you do that to me? They made fun of me today’,” Gali said.

The Health Ministry does not keep records on circumcisions but estimates about 60,000 to 70,000 are held in Israel every year, which roughly corresponds to the number of boys born in 2010, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics.

The ministry said it treats about 70 cases a year of circumcisions gone wrong, mainly minor complications such as excessive bleeding.

Kaufman said “people were shocked” to learn that her son is not circumcised.

“In Israel everybody does it, like a herd,” she said. “They don’t stop and ask themselves about this specific procedure which has to do with damaging a baby.”

Watching her son rummage through a stack of toys, Kaufman said: “The way he was born is the way his body should be.”