Forget being caught on camera at a Coldplay concert — I was caught on Shabbat at Yankee Stadium

A Jewish baseball fan remembers the game that outed him on national television

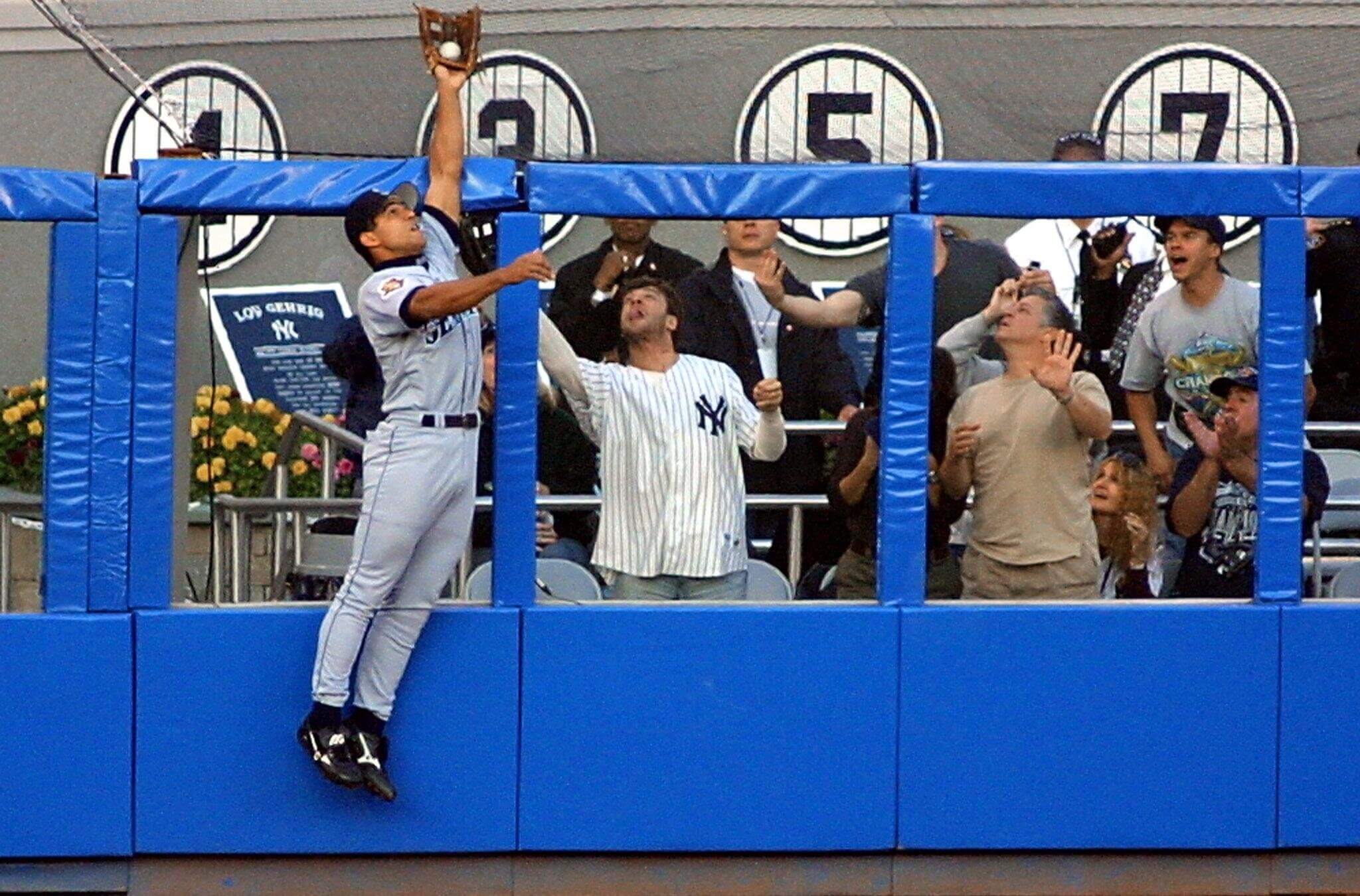

Seattle Mariner Stan Javier robs Alfonso Soriano of a home run — and the author of this article (pictured in Yankees jersey) of a souvenir. Photo by Getty Images

The illicit embrace caught last month on camera at a Coldplay concert gave me a shudder. It sent me back 24 years to when I too was caught on live national television — not cheating on a wife but violating Shabbat.

It was Oct. 20, 2001. I was 30 and I had not yet confessed to my parents that I was no longer shomer Shabbat. And on this Shabbat, as I drove to Yankee Stadium with a woman I’d recently begun to date, I had a feeling of unease. For there seemed to be a real chance that I might end up on national television. Fox cameras were stationed all about for the third game of a playoff between the Yankees and Mariners, and our seats were in the first row behind the left field wall — perfect for catching a home run.

There is something electric about catching a ball at a game. For a split moment, you are part of play. Twice I’d had that thrill, the last in 1993 when an 0-2 pitch flew from the right hand of Yankee pitcher Steve Farr to the bat of Red Sox first-baseman Carlos Quintana to my black leather Rawlings, high above first base. That glove was on my right hand when, now, Bernie Williams hit a two-run home run in the first. Ecstatic in my Williams jersey, I cheered wildly.

The score was still 2-0 Yankees when their young second baseman, Alfonso Soriano, led off the bottom of the third. He swung at the fourth pitch.

“Soriano hits one to deep left field,” called the announcer Joe Buck.

The ball was soaring toward me. I stood. I then stepped forward and to my right, and could see Stan Javier, Seattle’s veteran left fielder, running to where I was. He leapt and raised his left arm. I raised my right. My glove was near the top of the wall. But Javier’s arm rose high above it, his glove some two feet above mine. “A leap and a catch!” called Buck. “Stan Javier took a home run away!”

He had taken it away from me and I screamed in frustration. Then, in seconds, the thrill and adrenaline of the moment gave way to the recollection that it was Shabbat and that millions would now know that I was at the stadium in violation of it.

The fear of being outed is familiar to any former Sabbath observer. A friend of a friend was on the 2 train on a Saturday afternoon in 1984 when Bernhard Goetz opened fire; his first thought was that his parents would now learn he was no longer religious. Fourteen years before that, a Catholic woman photographed at the Woodstock music festival was mortified when she landed on its iconic album cover. “The picture was incriminating,” Bobbi Kelly told the press. “Proof that I did not go to Mass.”

The proof on this Shabbat that I did not go to synagogue was growing with every slow-motion replay of my reach for a ball. Fox had just shown it a third time when the announcer Buck noted that Javier had “robbed that guy behind him wearing the Yankee jersey of a souvenir.” Two pitches later — the count 1-1 on Yankee Chuck Knoblauch — Fox showed the catch yet again, this time in super slow motion. Buck returned to me.

“How many people were thinking, OK, I’m going to come home with a souvenir,” he mused — “especially that guy?” To make clear whom he meant, Buck circled my face.

I had considered, were a home run to be hit my way, that my face might flash across the screen. But this was absurd. I had been telestrated, as someone behind me with a pocket TV now let me know. My face felt hot. Buck soon circled it again. He may as well have added, “Here, America, is a man desecrating the Sabbath.”

Fox was not done with me. Seconds later, it showed me yet again — this time in super, super slow motion — my glove raised, my tongue stuck out in concentration, my mouth opening in a scream after Javier intercepted the ball. The broadcast cut to Derek Jeter grimacing in the dugout, and Buck quipped that Jeter’s reaction was “about the same as the guy behind the wall.”

My mind went to my parents. They did not watch TV on Shabbat. But I feared that someone who did might mention me to them. Still, there was nothing I could do. And when Knoblauch then stepped out of the batter’s box, and the fan with the TV told me that I was back on air, I leaned into the absurdity, smiling and waving my glove and shaking my head and shrugging and throwing my hands in the air. I was thinking about Shabbat, not a ball, but the announcers did their best to interpret.

“Aw c’mon!” said color commentator Tim McCarver.

“Oh, so close,” added Buck.

After Knoblauch struck out, and Jeter flied out to end the inning, Fox went to the commercial break with its cameras back on me — “the guy,” said Buck, “who thought he was going to get a souvenir.” I was on my cellphone — another thou-shalt-not — speaking to a relative whose sins were unseen.

Hours later, after the game, an ESPN writer emailed to ask if he might write about me and my near-catch. (I had, months before, written a much-publicized article about a cheating scheme in baseball.) I declined, explaining about Shabbat and my parents. The next day, The New York Times ran a large photograph of me and Javier. But my face was hidden, and best I knew, no one told my parents what I’d done.

The weight of a secret

It was not like me to keep a secret. I was secure in the life I lived. But in time, I understood why I had. My real worry was not that my parents would learn I’d violated Shabbat but rather that they would think I did not want to keep it. In truth, I loved Shabbat — that weekly respite from daily life and its bombardments. I knew I’d return to it. And I did.

A few months ago, I was speaking with my mother. She was dying, and we were filling in missing pieces, things not said before. My mind returned to Yankee Stadium and I confessed my sin. My mother listened and smiled. “I’m sorry that you had to keep that inside,” she said.

So was I.