Every Polish Town Had Own Holocaust

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

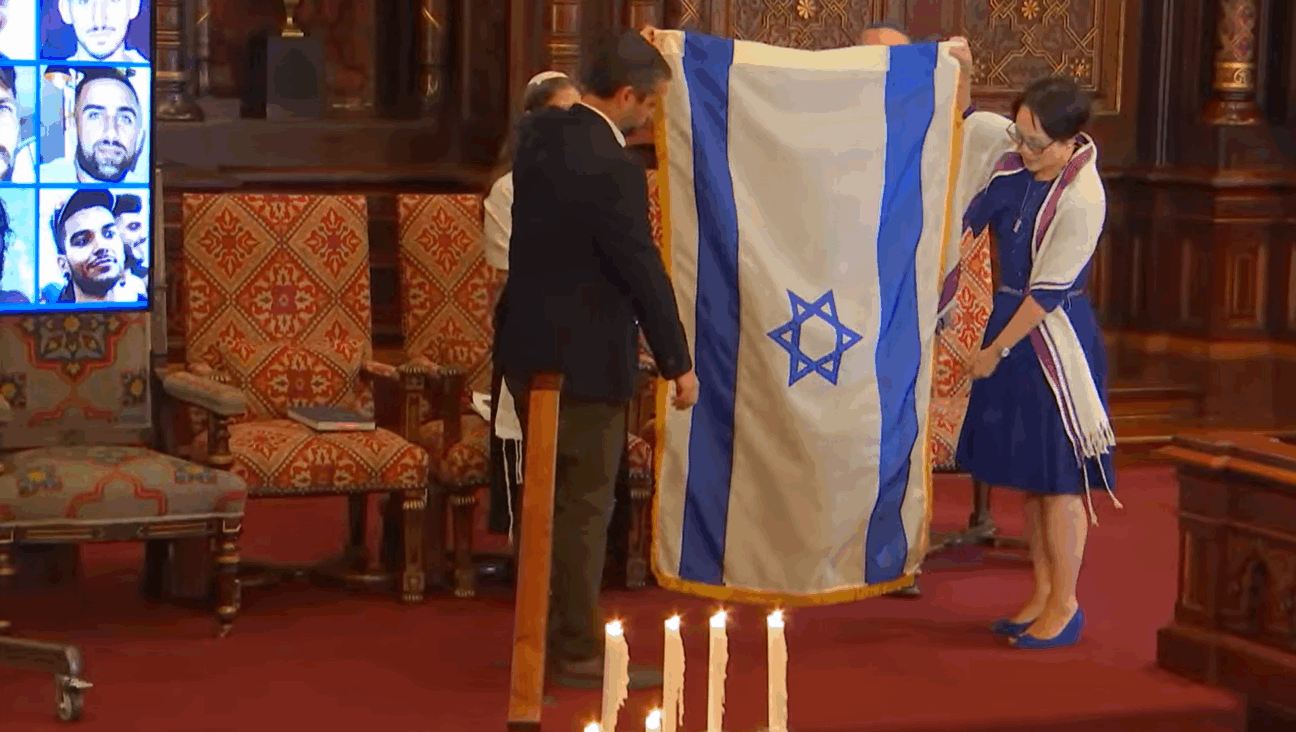

Learning About Lost Past: Polish young people in the town of Chelm learn about a Jewish community that was wiped out in the Holocaust. Image by courtesy of School of Dialogue

Every Polish town and village had its own Holocaust. That’s what Zuzanna Radzik wants Polish children to learn.

Her task is not easy. Although Polish children are taught about the Holocaust, they don’t learn what happened in their own towns.

The killing did not just happen in the death camps that they are taught about, such as Auschwitz and Treblinka. It also took place in little known towns like Stoczek Wegrowski where 188 Jews were shot to death on Yom Kippur of 1942, September 22.

Jews comprised as much as 70% of the population in some towns and villages in prewar Poland.

“We bring history to children in towns and villages who have never met a Jew or seen a synagogue,” Radzik said in a telephone interview with the Forward. “When we show them where the ghetto was in their town and that Jews were killed there, it all becomes real.”

Radzik represents a vanguard of Poles who believe that the Jewish heritage in Poland is an integral part of Polish history and that Poles must learn about it to understand contemporary Poland. In Poland today, she is far from alone.

Another Pole in search of Poland’s lost Jewish history, Beata Chomatowska, is restoring the memory of the Warsaw ghetto in the city’s Muranow neighborhood, which is built on the rubble of the former Jewish quarter.

Yet another Pole memorializing the country’s lost Jews is Zbigniew Nizinski, who bicycles through flat, pine-covered eastern Poland looking for the unmarked graves of those murdered in the Holocaust. He is motivated by his Baptist faith.

Faith also motivates Radzik, a 28-year-old theologian and devout Catholic. “We have a long history of Christian anti-Judaism,” she told the Forward. “We should do our repentance for that and be strong about fighting anti-Semitism.”

Radzik supervises a program known as the School of Dialogue, intended to recapture the lost history of the Jewish presence in Poland. The program is under the auspices of the Forum for Dialogue Among Nations, a Polish not-for-profit organization that fights anti-Semitism and works to foster better relations between Poles and Jews. Radzik is a member of the forum’s board of directors.

Under her direction, the School of Dialogue deploys educators throughout Poland to make students aware of the places in their towns where Jews once lived and worked, and where there were synagogues and mikvehs. They also teach young Poles about Judaism.

The educators highlight the shared religious truths of both faiths. To illustrate the point, they show Catholic and Jewish calendars to the students to make them aware of the holidays in both religions.

In April 2011, two School of Dialogue educators visited Kielce, where 24,000 Jews lived before the war, about one-third of the city’s population. Almost all of Kielce’s Jews were murdered during the Holocaust.

Ania, one of the teenage participants in the School of Dialogue program in Kielce, wrote, “I’ve been living here since I was a baby, and I did not know the meaning of the monuments for Holocaust victims I passed by every day and where the Jewish cemetery is.” As a result of the program, she now does.

Like Radzik, Beata Chomatowska, seeks to bring to life Poland’s Jewish past. The 34-year-old journalist, who lives in Muranow, where the Warsaw ghetto stood, has created the website Stacja Muranow (Muranow Station) to educate residents about the history of the place in which they live.

From this place, 300,000 Jews were sent to death camps. Hundreds of others are buried in the ruins. The Germans leveled the Warsaw ghetto after the Jewish uprising there, in April 1943.

“This area is still dead 68 years after the Germans destroyed it,” Chomatowska said, speaking with emotion. “It is my obligation to remember the people and the place that was here before.”

There are no physical reminders of the former Jewish neighborhood, which makes it difficult to visualize its former appearance and recapture its history. Its hilly terrain in some places results from the fact that since much of the rubble could not be cleared, the new housing was often built on mounds of ruins.

Chomatowska is especially proud of recently completed murals by Warsaw artist Adam Walas in the entranceway to an apartment building at Nowolipki Street 13. This artwork features prominent Jews who lived in Muranow before the war, like Ludwik Zamenhof, creator of Esperanto.

Zamenhof intended Esperanto as a common language that would unite people of different cultures. “I transferred Zamenhof’s hope to the mural with hope that people would see what is universal,” Walas said.

Thirty other Muranow residents have joined Chomatowska’s education project. They meet in a still-unfurnished ground-floor office at Andersa 13 in Muranow. It is their hope that this will become a meeting place where Muranow residents and Jewish visitors can learn about the district’s Jewish past.

Asked what has motivated her in her project, Chomatowska said, “I was always interested in Jewish culture and history, and a world that disappeared.”

Like Radzik and Chomatowska, Zbigniew Nizinski brings to light a world that has disappeared. Inspired by the Bible and by a fervent belief that the memory of the dead must be preserved, Nizinski has dedicated his life to finding the unmarked graves of Jews murdered by the Germans and to identifying those who were killed.

The unassuming 52-year-old Baptist travels to the tiny villages in the pine-and-birch covered lands of eastern Poland. “We discover and rescue the graves from complete oblivion and place memorial stones,” Nizinski said during an interview in Warsaw. “They no longer remain anonymous.”

Nizinski says it is his purpose to remember those who have been forgotten. “It is so unjust that there are so many Jewish burial sites that are not visited because there are no relatives left,” he said.

Nizinski travels to small towns, usually by bicycle, and speaks to elderly people who still remember where murdered Jews are buried. That’s how he met 90-year-old Wladyslaw Gerula near Przemyśl, a picturesque town in southeastern Poland.

Gerula’s parents were taken from the family farm and killed by the Germans because they had been hiding Jews. Their burial site is unknown, but Gerula knows where the three Jews his parents were hiding, whom the Germans also killed, are buried. Gerula has placed a large stone on this spot and carved a Magen David on that stone. He also considers it to memorialize his parents. Nizinski is helping Gerula search for the identity of these Jews so that their names can be inscribed on the stone. Gerula’s parents were honored at Yad Vashem on April 25, 1995.

One of the many unmarked graves that Nizinski has discovered is near the small town of Stoczek Wegrowski. Buried here are Rywka Farbiarz and seven other Jews murdered by the Germans on November 26, 1942. Farbiarz’s 10-year-old daughter, Chasia, survived the massacre because the bullets missed her and she lay silent beneath the dead. Later hidden in the woods with other Jews, she was helped by a local Polish family.

Chasia Farbiarz, who now lives in Israel, visited the grave with her two sons on June 16, 2011 for the unveiling of a memorial stone that Nizinski placed there.

Nizinski works closely with Michael Schudrich, chief rabbi of Poland. Schudrich encourages Nizinski to continue his work, and he has helped get modest funding for it.

Nizinski, Chomatowska and Radzik, each in his or her own way, work to reclaim the Jewish history that the Holocaust brutally aborted. They are not alone. Their work reflects the growing recognition that Poland’s Jewish history is an integral part of the Polish past.

According to author Konstanty Gebert, a columnist for Gazeta Wyborcza, many Polish historians are learning Hebrew and Yiddish in order to be able to use Jewish sources for Polish history.

Alina Molisak, who teaches Jewish literature at Warsaw University, cites the tremendous influence that Jewish authors have had on Polish literature.

When asked what Polish literature has lost with the absence of Jews, she answered, “Everything.” She went on to say, “You can feel the Jewish absence, not only in literature, but in culture and science. We miss them.”

Contact Don Snyder at [email protected]