What Harry Reid Said, and What He Meant

If you’re like me, you probably just spent a weird stretch of January staring at your television, vainly trying to figure out what our national leaders could be talking about this time. Political gibberish is nothing new, but lately the nonsense has reached new heights.

Here’s what I got: It had something to do with Harry Reid, the charisma-challenged Senate Democratic leader, and something offensive he said about black people, and now somebody on television wants him to resign. After that my brain froze.

Happily, things started coming into focus after a nice nap. What we have here, I figured out, is a fairly ordinary case of gotcha politics: Somebody speaks overly frankly at an unguarded moment; somebody else twists it around and whips up a scandal; accusations of hypocrisy get hurled in every direction, and everyone ends up wounded or soiled. So far, not terribly edifying.

What’s instructive is how this case turns clichés on their heads and recasts the traditional plot line. It’s standard practice for minorities to defend themselves from prejudice by watching for bigoted code words and then shaming the speaker. Bad speech precedes bad behavior, we assume; ergo, stop the speech, prevent the behavior. This time, though, the speaker happens to be a leading defender of the minority he’s supposedly slurring, and right now he’s in the fight of his life. So his supposed victims rally around him.

Conversely, conservatives have long complained that restricting biased speech — that is, political correctness — is used as a ploy by liberals and minorities to gain advantage by using victimhood as a weapon. This time, though, conservatives have caught a liberal in flagrante incorrecto, and they’re flogging it to the hilt.

Maybe it’s just me, but when everybody is rushing to abandon their positions on hate speech the moment they’re inconvenient, I suspect that nobody meant what they said in the first place.

To review: Reid is under fire for a comment made two years ago that just came out and sounds bigoted. During the 2008 presidential campaign, according to a new book, Reid had explained why he thought Barack Obama could win. Reid believed, the authors wrote, “that the country was ready to embrace a black presidential candidate, especially one such as Obama — a ‘light-skinned’ African American ‘with no Negro dialect, unless he wanted to have one,’ as he said privately.”

Well, you know what happened next. Reid reaped the whirlwind. Critics accused him of racial insensitivity for using the word “Negro,” supposedly a slur, and of seeking to divide Americans by skin color. Some leading Republicans are demanding he resign.

Curiously, the complainants were largely white. Most black opinion-makers agreed that while Reid’s words were inept, he was correct on the substance — that America has overcome much racism but not all, and that darker skin and so-called Black English still carry a stigma. Obama himself said Reid “used some inartful language in trying to praise me.”

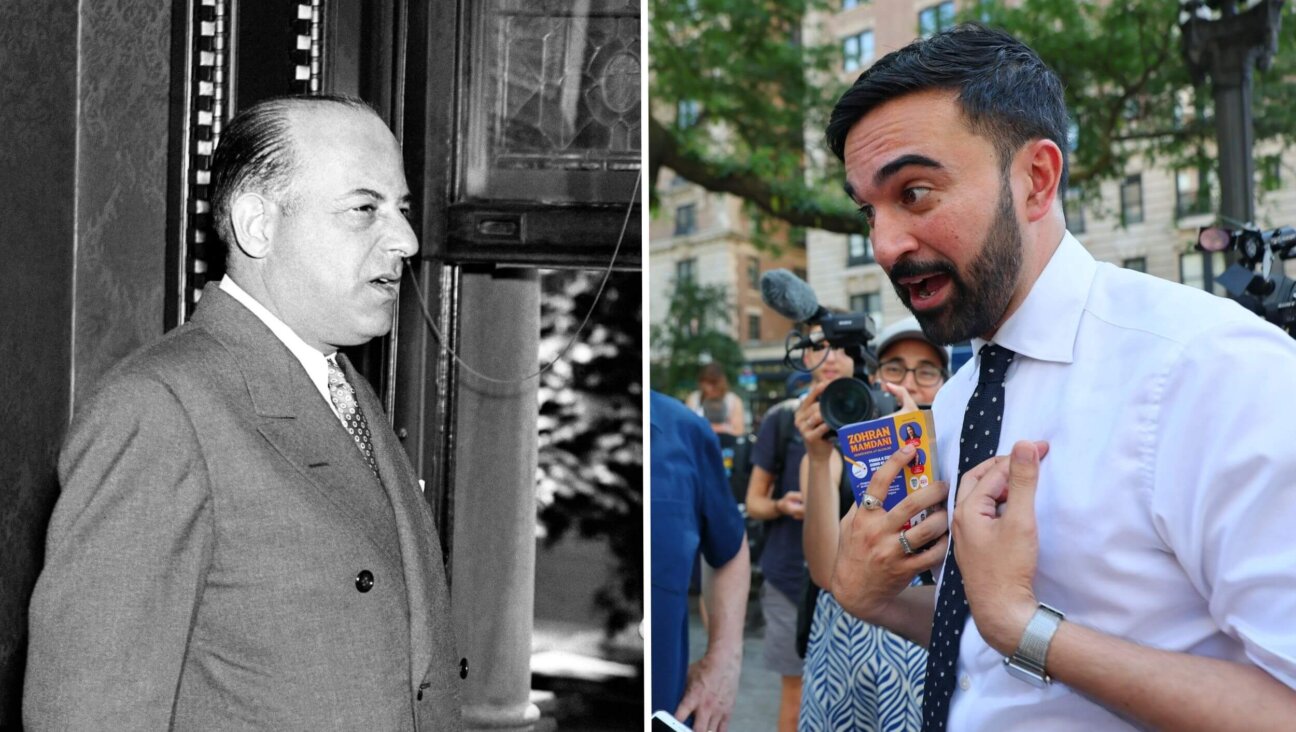

The strongest critics, in fact, were Republicans complaining of a double standard. Back in 2002, they recalled, Senate GOP leader Trent Lott was forced to resign after inartfully saying, at a 100th birthday party for South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, that America would have been better off if Thurmond had won the presidency when he ran in 1948 on a segregationist third-party ticket. If Lott had to resign in 2002 for racially insensitive remarks, some top Republicans argued, Reid should have to do the same in 2010.

The Reid-Lott comparison is ludicrous, but quite revealing. Lott wasn’t pilloried for clumsy language, but for explicitly endorsing Jim Crow — and not for the first time. Assuming Reid’s current critics mean the comparison seriously and aren’t just taking potshots, hardly a safe assumption, it means they’re unable — or unwilling — to see the difference between observing the decline of racial segregation and lamenting its decline.

Is there a lesson in all this? Here’s an important one: Be wary of using biased speech and code words to measure racism. It’s a very inaccurate tool. Back in 1992, the Anti-Defamation League surveyed American opinion to measure levels antisemitic prejudice. The ADL had been measuring antisemitism since the 1960s. Its survey offered 11 true-or-false stereotypes about Jews, including that Jews “always want to be at the head” and “only care about their own.” Five or more “true” answers constituted antisemitism. More than one-third of black respondents recorded five or more. In focus groups, however, many blacks saw some of the stereotypes — ambitious, caring for their own — as positive. Some openly wished the black community could learn from the Jews.

The mistake happens over and over. In 1996, Marlon Brando told Larry King that “Hollywood is run by Jews,” and was pilloried for it. It sounded like conspiracy-mongering. In fact, Brando, a lifelong, passionate Zionist, was talking about stereotyping of blacks in movies. Jews “should have a greater sensitivity” to human suffering, he told King, because of their history and their values.

As it happened, Universal Pictures was in the midst of a succession battle at the time. At its height, The New York Times ran a box showing the chairman and president of Hollywood’s top 10 studios. Of the 20 studio heads, one was gentile.

Back to Reid: His argument in 2008 was, in effect, that Americans had made some progress against racism — but only some — in the 45 years since Martin Luther King Jr. voiced his dream of freedom. King dreamed in 1963 of a nation where his own children would “not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” We’re not there yet, Reid was saying. We value character over color, but we still favor selected tints.

King went on to say in his speech that 100 years after Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, “the Negro still is not free.” What would King say if he came back today? For starters, he’d probably have to apologize for his inartful phrasing.

Contact J.J. Goldberg at [email protected] and follow his blog at blogs.forward.com/jj-goldberg