Rescind the Ban on Attending Interfaith Weddings

When I decided to become a rabbi in 1996, I visited the Jewish Theological Seminary, my future rabbinical school. Along with sitting in on some classes, I stayed in the apartment of four first-year rabbinical students. I still recall a discussion we had at the Shabbat dinner table. One of the rabbinical students raised the question of what would happen if one of their siblings became engaged to a non-Jew — could they even attend the wedding?

The Rabbinical Assembly, Conservative Judaism’s rabbinic organization, lists attendance by a rabbi at a wedding between a Jew and a non-Jew as a violation of its “Standards of Religious Practice” in its code of professional conduct. The underlying rationale is that a rabbi’s attendance at an interfaith wedding would be perceived as condoning intermarriage.

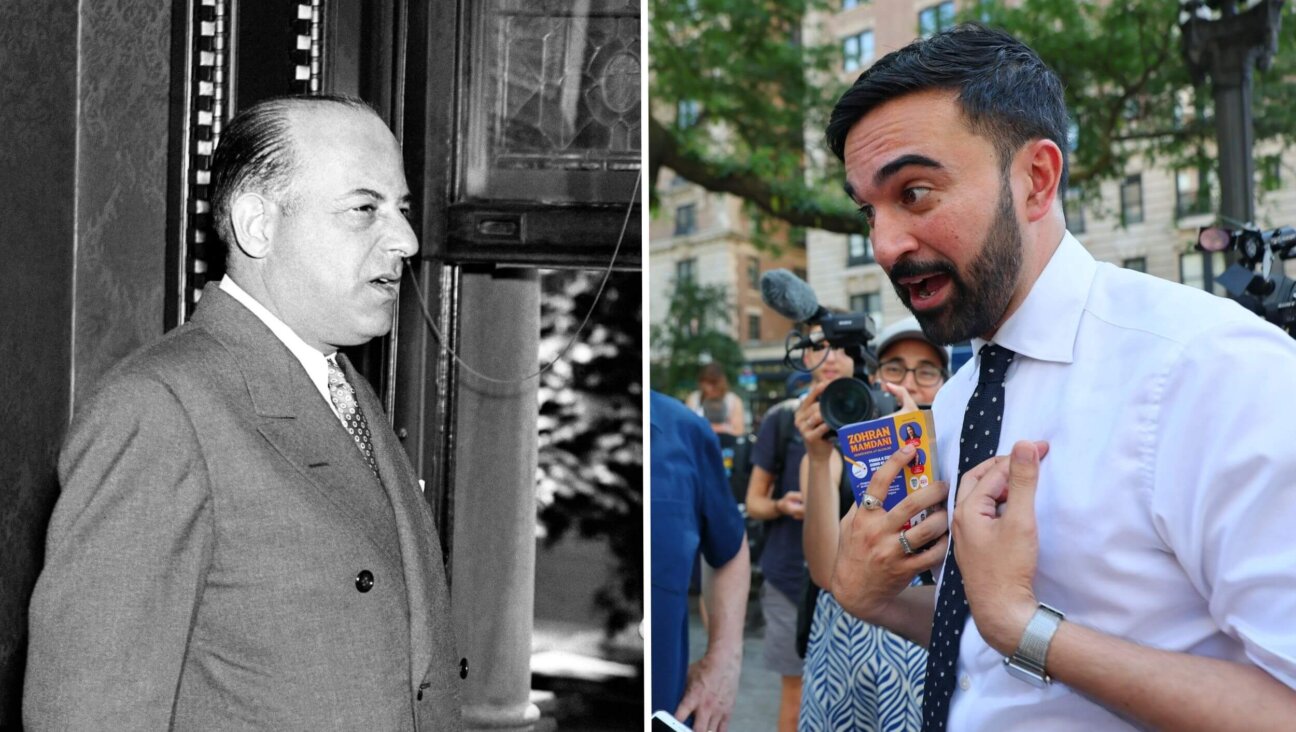

While the recent wedding of Chelsea Clinton to Marc Mezvinsky renewed age-old debates about intermarriage, for Conservative rabbis in particular it has spurred discussion about the R.A.’s policy. This is because JTS’s chancellor, Arnold Eisen, attended the couple’s post-wedding reception.

Eisen — who became close to the groom when he was a professor at the couple’s alma mater, Stanford University — is not a rabbi. Yet chancellors of JTS are considered by some to be the Conservative movement’s titular heads. Is it possible for the chancellor of JTS to attend an interfaith wedding reception without implicitly sending a message either about the Conservative movement’s attitude toward intermarriage or, more specifically, about the appropriateness of the R.A.’s policy?

In truth, if Eisen were not such a high-profile figure, he would not have been breaking new ground. In practice, the R.A.’s policy has left considerable room for interpretation. Some R.A. members distinguish between attendance at an interfaith wedding ceremony and the reception that follows. Others disagree, arguing that the wedding ceremony is directly connected to the actual ceremony and attendance at either could be perceived as tacit approval. Some rabbis, however, have simply flouted the policy, quietly attending interfaith wedding ceremonies of relatives and friends.

The R.A.’s code states that violations of standards of religious practice “usually result in expulsion from the Rabbinical Assembly.” Rabbis who officiate at interfaith weddings face the prospect of stern sanctions from the R.A., and in practice have generally chosen to resign their membership in order to avoid public controversy.

I am not, however, aware of any instances in which rabbis who simply attended interfaith weddings (and I know more than a few who have) faced repercussions from the R.A. Indeed, one widely held view among R.A. members is that the real purpose of the attendance ban is to give Conservative rabbis who personally oppose attending such weddings a ready excuse when invited.

Nevertheless, the policy presents many of us with profoundly difficult choices. A couple of years after I was ordained at JTS, I chose not to attend my first cousin’s wedding to a lovely, albeit non-Jewish, young woman. I explained that my wife and I would not be attending because my rabbinic association forbade it. My refusal to attend (he knew better than to ask for me to officiate) led to animosity from other relatives and a fractured relationship among cousins.

In light of the fallout from that decision, I made a much different decision several years later. When I received an invitation to the wedding of a close childhood friend, I didn’t allow the fact that her bashert wasn’t a “member of the tribe” to deter me from replying “yes” on the RSVP card. I don’t believe anyone in attendance saw my presence as an acceptance of intermarriage. My intention was only to show support for my long-time friend and to ensure the couple knew that the Jewish community wasn’t turning its back on them.

The R.A. isn’t about to allow its members to officiate at interfaith weddings. But the attendance ban, which is listed in the code of conduct alongside the officiation ban, is a different issue. This policy forces rabbis to choose between violating a rule and slighting loved ones. The policy, enforced or not, adds pain to an already difficult situation for families. It sends a message that Judaism puts tribalism before dignity and respect.

It is time for the Rabbinical Assembly to rescind its policy banning its members from attending interfaith weddings as guests. If outreach to interfaith couples is a goal for our movement and our community, then the insult of refusing to attend their weddings is counterproductive.

Rabbi Jason A. Miller is rabbi of Tamarack Camps and director of the Kosher Michigan certification initiative.