Romney’s Vision of Capitalism

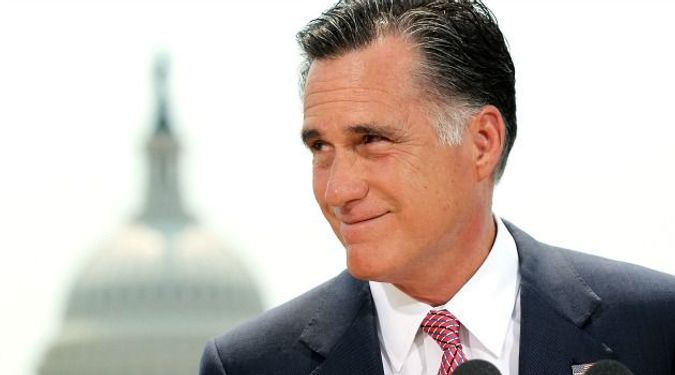

Image by getty images

Willard?s World: Mitt Romney?s Bain Capital claims to be the epitome of risk-taking capitalism. In reality, Bain was playing by the rules: heads we win, tails you lose. Image by getty images

Capitalism in its purest form is gambling. Ask any entrepreneur. You have an idea for a product or a service; you bet on your premonition that there is a market for it, and you roll the dice. Then you either win or lose. That’s a simplistic rendering, but it is the basic gist of our economic system.

This is pretty much the sentiment captured in the company statement of Bain Capital, the private equity firm that is the jewel in the crown of Mitt Romney’s business career. It explains that Bain’s objective is to buy up struggling companies, offer a new infusion of cash, then restructure those companies and hopefully turn them around.

It’s based on this intimate knowledge of the ups and downs of capitalism that Romney has made the claim that he’s better equipped to handle the economic crisis — better, that is, than the current occupant of the White House. He understands, he says, the “real economy.” And whenever his time at Bain has come under attack, Romney answers that an attack on Bain is an attack not on the business practices of private equity, but on the very nature of free enterprise itself.

“There’s no question he’s attacking capitalism,” Romney said about the president at an event in Philadelphia on May 24. “In part I think because he doesn’t understand how the free economy works…. Frankly, the American people understand that the free economy and free enterprise is tough; it’s hard work.”

But was Bain engaging in capitalism as I just sketched it out above — a game of risk with potentially high rewards or dismal loses? If Romney wants to point to Bain as his idea of “how the free economy works,” we should take him at his word and follow him there. What we’ll find, I’m afraid, is not exactly Adam Smith. Instead, it’s a vision of capitalism in which that game of risk is almost completely rigged.

Capitalism as a pure concept does not exist, not even in laissez-faire America. Government offers tax breaks and subsidies to encourage businesses it deems important, and a social safety net is in place to catch those people who end up inadvertently suffering from the volatility of market forces. All these factors mitigate what otherwise would be the harshness of the invisible hand. So the particular version of capitalism that a candidate pushes forward — which of these mitigating factors he prioritizes — says a lot about his moral vision. If we understand that the barest form of capitalism is inhumane, then a choice exists about who should suffer the risks of the system.

This brings us back to Bain, held up by Romney as an exemplar of capitalism at work.

Let’s look at what happened when things didn’t work out for Bain. It’s easy enough to point to the successes, but as Romney said, sometimes the going gets tough. Specifically, seven companies acquired by Bain eventually went belly-up. Did the private equity firm learn the downside of capitalism? Not really, according to a June 24 article in The New York Times.

The Times examined those seven cases and found that to a very large extent, the managers at Bain didn’t really suffer any economic repercussions as the bankrupt companies lost everything and had to lay off hundreds of employees. As the Times put it, “Bain structured deals so that it was difficult for the firm and its executives to ever really lose, even if practically everyone else involved with the company that Bain owned did, including its employees, creditors and even, at times, investors in Bain’s funds.”

The key was that Bain knew how to hedge its bets against any real loss, mostly by charging the acquired companies exorbitant fees whether or not they could afford to pay them. In some cases, these companies sank deeper into debt just so they could replenish Bain’s coffers.

The article covers all seven cases of bankruptcy, but one will suffice to give an idea of how this worked. In 1993, Bain acquired a struggling Midwest steel manufacturer, GS Industries, for $8.3 million with the plan of modernizing it. A year later the steel company, still in bad shape, had to issue $125 million in debt, some of which was used to pay a $33.9 million dividend to Bain, money owed on its initial investment. Bain put in an additional $16.2 million before the company eventually filed for bankruptcy in 2001. You would think this sad history would have put Bain’s investors in the red. But no, they still made a total of $9 million on the deal, not to mention that Bain’s managers got additional millions in fees from the ailing steel factory as it died a slow death.

In other cases the returns were even greater, with investors making more than $100 million in profit from companies that went bankrupt and with the fees extracted by Bain rising to the tens of millions.

To be fair to Romney, as the Times put it, this is merely the way private equity functions, “offering its practitioners myriad ways to extract income and limit their risk.”

Jews have historically opted and even fought for a form of capitalism that protects the most vulnerable from the vicissitudes of a market economy. For the system to work as marvelously as it does, someone has to take on the risk. Over the past century, countless union organizers and progressive activists have argued that it should be borne by the investors who decide to gamble. Instead, Bain’s capitalism looks more like a form of exploitation, producing more money for those who already have money without jeopardizing anything. Meanwhile, the burden of the risk falls on those least capable of bearing it.

Nobody in mainstream American political life is attacking capitalism. But what should be under attack is the kind of capitalism that Romney is apparently holding up as an ideal, one that not only further entrenches the growing inequality between the 1% and everyone else, but even takes risk out of the equation so that the rich get richer no matter how the dice fall.

Contact Gal Beckerman at [email protected] or on Twitter @galbeckerman