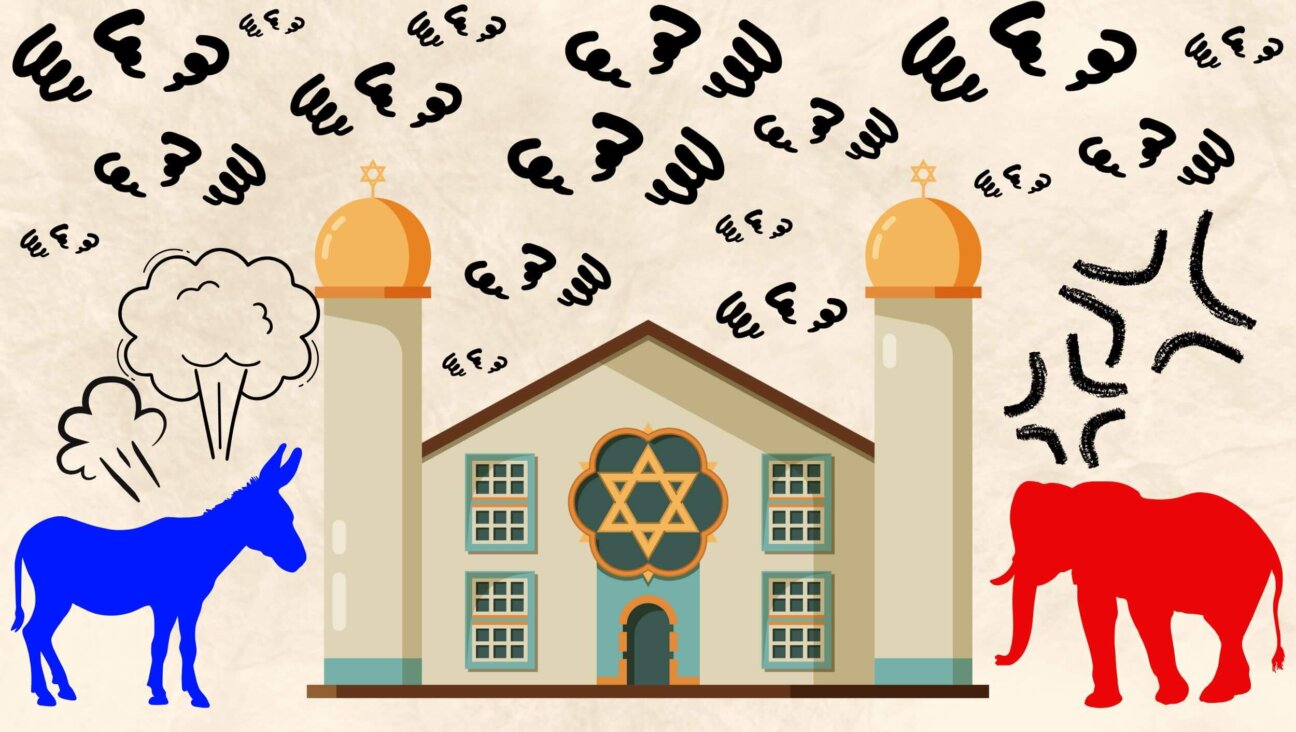

Obama and Netanyahu Need One Other, But Neither One Has Room To Maneuver

Image by getty images

When President Obama’s helicopter convoy deposits him in Jerusalem on March 20 for talks with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, it will bring together two leaders who, despite their famed mutual antipathy, have far more in common than either man’s partisans would readily admit. It’s a perfect recipe for trouble.

Both men have come fresh off re-election campaigns that dealt each of them a dramatic reversal of fortune. Netanyahu had just completed a successful four-year term marked by economic prosperity and quiet borders. Israel’s voters rewarded him with a drubbing that erased one-third of his parliamentary strength. Conservative columnist Ben-Dror Yemini calculated in Maariv after the January 22 election that a total of 265,000 voters, 7% of the electorate, had moved from the right to the left (just as you’d expect in a Hebrew-speaking state). The shift turned the right’s previous 227,000-vote advantage into a 38,000-vote deficit. Netanyahu’s tortuous, white-knuckle struggle to negotiate a new coalition was merely a symptom of his weakened condition.

Obama’s reversal was the mirror image of Netanyahu’s. After a first term marked by recession, unemployment, legislative paralysis and dismal approval numbers, voters re-elected him with a convincing mandate, a strengthened Senate majority and a popular-vote win, if not a working majority in the House of Representatives.

Where it counts, though, the two leaders share a critical liability: Each faces a nettlesome bloc of lawmakers who refuse to recognize their party’s electoral losses and promise to fight single-mindedly for the agenda the voters just rejected. In Obama’s case, we’re talking about the Republican-led House. In Netanyahu’s case, it’s a group of hard-line young Turks in his own Likud party who did well in last fall’s party primary, edging aside veteran moderates like Dan Meridor and Benny Begin. Their extremism arguably contributed to the party’s losses in the general election. Regardless, they now consider themselves the rising voice of what’s still the ruling party.

Thanks to their parliamentary headaches, the two leaders are now caught in strikingly parallel situations. Both are their nation’s unchallenged leaders and yet, paradoxically, both have little room to maneuver at a moment when their countries face critical decisions.

That’s the baggage that the two men will carry with them when they come together in Jerusalem on March 20. Each approaches the other from a position of weakness, wounded, wary, hoping for cooperation yet suspicious of the other’s intentions. Each has important assets to offer the other, both in the international arena and on their respective home fronts. If they can overcome the obstacles, they might be able to help each other. They could just as easily undercut each other, under pressure from their respective rear guards and their own contrary instincts.

On the most visible level, each holds diplomatic cards that the other needs. Obama needs a commitment from Netanyahu not to surprise him with a military raid on Iran that could drag America unwillingly into the fighting. Netanyahu needs a commitment from Obama that if Israel holds back and then finds Iran going nuclear, America will take action.

It sounds simple enough, but it’s anything but. Each leader is being asked for a commitment that takes him way outside his comfort zone and risks angering his political base. Each one’s commitment is contingent on the other keeping his promise. And neither trusts the other’s promises.

The Palestinian issue is even more complicated. Obama has promised not to present Netanyahu with any new plans or demands during this visit. He is planning, however, to press Netanyahu to come up with ideas of his own. Obama doesn’t have high hopes for a seriously revived peace process, but he knows that America’s European allies are increasingly impatient for some sign of progress. Netanyahu knows the same thing. All three — Netanyahu, Obama and the Europeans — are aware that the Palestinian street is on the verge of eruption.

Despite his own history, Netanyahu is reportedly ready to take a significant step toward the Palestinian leadership, in order to shore up Mahmoud Abbas and open the way toward some interim agreement. He’s promised as much to Tzipi Livni and Yair Lapid in the course of coalition negotiations. Unfortunately, he’s been handed a government — largely at Lapid’s insistence — that includes Naftali Bennett’s settler-backed Jewish Home party, which opposes Palestinian statehood in any form. Together with the upstart Likud hard-liners, Jewish Home might be able to veto any significant gesture that could bring the Palestinians back to the table.

The leaders’ domestic political agendas are less obvious, but no less compelling. Obama needs Israel to receive him warmly. Demonstrating a strong relationship with Israel and Israelis would help disarm some of his harshest critics at home. That’s no easy task, given Israel’s history of suspicion toward this president. He can’t generate the warmth by himself. No matter how much stagecraft his advance team puts together, he needs Netanyahu to embrace him.

Netanyahu, on the other hand, needs to show his public that he’s capable of standing up to Obama. Embracing the American president has no real political benefit for Netanyahu right now. He needs to treat Obama as coolly as he can get away with while still collecting whatever goodies he can extract.

In the end, each leader needs to get as much as he can from the other while giving away as little as he can, all the while maintaining an appearance of friendship that’s warm enough to please Obama’s domestic audience without alienating Netanyahu’s. It would be a tricky juggling act for a couple of players who were operating from a position of strength and trusted each others’ moves. For Barack Obama and Benjamin Netanyahu it will take something close to a miracle.

Contact J.J. Goldberg at [email protected]