Ani DiFranco’s Slave Plantation Gaffe

Image by Getty Images

At first glance, it seems that Ani DiFranco has become the latest example of how a mix of star-fueled insulation from the real world and white privilege can lead to bad public relations. After an Internet-inspired backlash, the feminist singer-songwriter has canceled a musical retreat at a former slave plantation in Louisiana, now a resort that promotes the quaint imagery of antebellum life.

But the dreadlocked diva isn’t to blame. Many have wondered how the normally socially progressive artist could be so insensitive. The answer is that for more than a century, since the South lost the Civil War, it has buried the horror of slavery to such an extent that celebrating at a site of such human suffering doesn’t seem so absurd. That a place like the Nottoway Plantation, where DiFranco wanted to have her event, exists as a luxury destination for weddings and other celebrations is telling enough. This is just one example of both collective amnesia and resilient pride in a racist ideology.

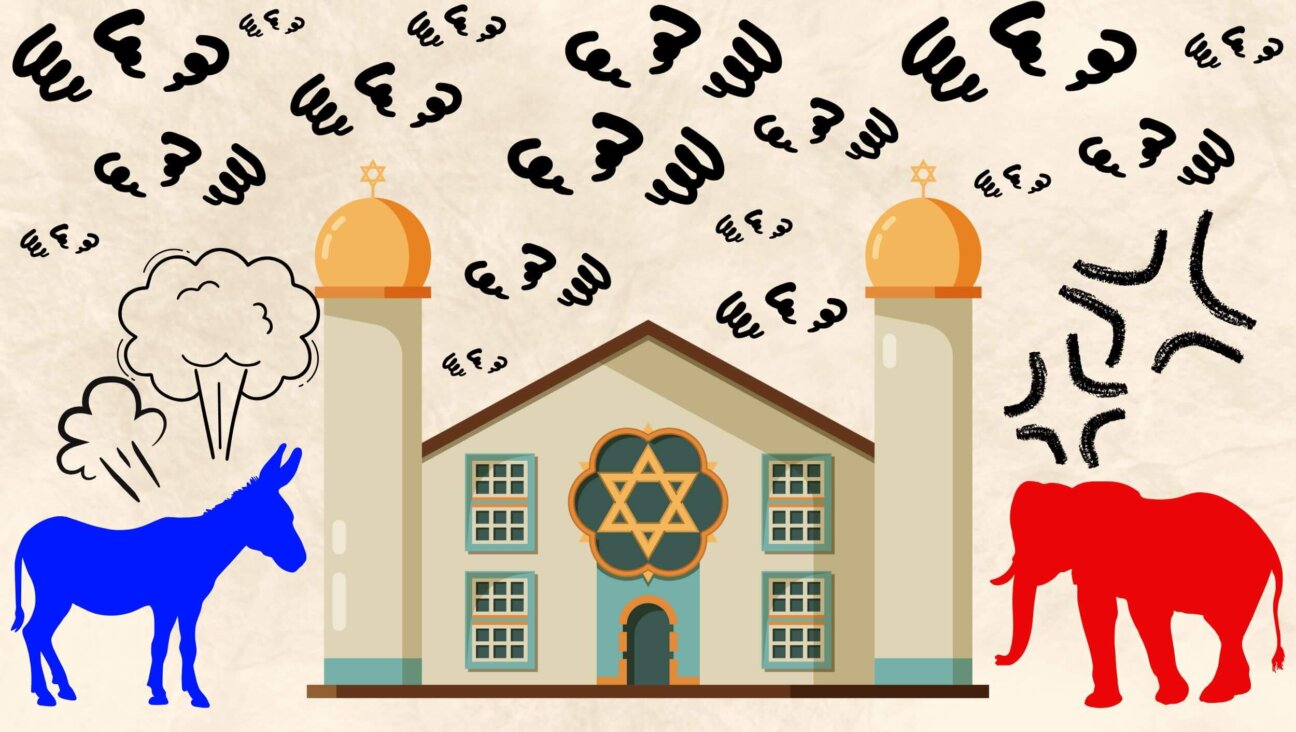

The fact is that it’s not that hard for a society to publicly condemn its own past and actively work toward a better future. As Jews, we know that Germany’s monuments to the Holocaust explicitly define the dead as victims of the nation. Those who resisted have museums in their honor. The death camps, both in Germany and outside, remind us of the dark possibilities of the human spirit, a sign that regular people can participate in unspeakable evil. Nothing about that era is celebrated.

By contrast, the South only concedes that it suffered a military defeat — burying the fact that the Confederacy was explicitly defending the ownership of people and white supremacy — and never admits that since the Confederacy waged war against the United States government, generals like Robert E. Lee share a lot in common with Osama bin Laden. That’s unfair, actually. Bin Laden wasn’t responsible for anywhere near the number of American deaths caused by Lee and company.

Instead, Lee’s birthday is a holiday in several Southern states, which just happens to fall near Martin Luther King Day. There is also a separate Confederate Memorial Day, in part because the federal Memorial Day, which honors American troops who died in war, was started by Union veterans. The Confederate battle flag is still a common site. The likeness of Lee, along with Jefferson Davis and Stonewall Jackson, is engraved on Stone Mountain, serving as a Confederate version of Mount Rushmore. I recently joked to a friend in my hometown of Atlanta that I should move back and open a Union Army-themed bar called Sherman and Grant’s, named for the top Union commanders. He suggested that I buy fire insurance.

Meanwhile, monuments to the civil rights struggle in the South are pushed to the dustbin. The MLK memorial center in Atlanta has descended into mediocrity. A few years ago, I was biking in New Orleans and stopped to read a historical marker in a landscape defined by rusted train tracks and overgrown lots. It was the site of Homer Plessy’s arrest for sitting in a whites-only train car in 1892, which resulted in the Supreme Court case that validated racial segregation.

The South’s defensiveness in it rosy remembrance of its own past is grounded in the excuse that the Union Army ravaged the South, including burning down Atlanta, in the final days of the war and during its occupation afterward. This doesn’t pass moral muster. It is true that civilians suffered as a result of the war, but it was a war the South started. And no war comes without crime, even on the side maintaining the moral high ground. The Allies committed atrocities during World War II, but this did not vindicate the Nazis’ quest for world domination.

Until there is collective contrition in the South about slavery and the Confederacy’s war against America in order to preserve one race of people as property of another, we’re never going to see an end to things like the DiFranco incident. And the will to make amends, to make the Nottoway Plantation look more like Auschwitz does today, has to come from within the South. If it comes only from Northern residents like myself, any effort to change consciousness will be seen in terms of an outside culture imposing its norms onto the South. And we know how much will the South has to resist something like that.