The Difficulty, and Ease, of Uprooting Jews

We are only days away from the lowering of the last Israeli flag in Gaza and the withdrawal of the last Israeli soldier. As one of the Jewish people’s and the Zionist enterprises’ most moving and profound dramas comes to a conclusion, many pens and keyboards will pour forth with punditry and wit of greater or lesser insight and value. There will undoubtedly be both inner and public struggles to gain perspective and understanding as to the meaning and significance of Israel’s first formal and final relinquishment of claim on territory of the Land of Israel.

No matter where one stands on the political spectrum, there will be a struggle to understand what it means, to the future of the state and the Jewish people, to have lost one of the greatest battles of the past century: the battle for settlement throughout the land. For surely, we have lost that battle, though I believe that it is possible to lose even a great battle and not to have lost the war. The vision and dream of settling the whole Land of Israel is not lost forever. History is often full of unexpected turns of events.

Beset by visions of expulsion and destruction, it cannot help but to appear that the victory of 1967 is somehow tarnished, lessened and in some ways even for naught — if we forget for a moment that the war was fought not to gain territory but to stave off destruction. A victory that was of such biblical proportion that even a secular writer like the late Leon Uris was moved to write an essay called the “Third Temple” is a victory that transcends one lost battle, however traumatic. Not only did the Six-Day War bring territory, greater security and even prosperity, but it also was a watershed in Jewish identity throughout the world, and it played no small part in the revival of Jewish life in the Soviet Union and an important role in the downfall of that once powerful colossus.

Nor are the achievements, the valiance or the heroism of the settlers themselves any less valiant or heroic against the background of bulldozers, rocks and rubble where there were only a few days ago roses and gardens and bit of paradise. The beauty of what they built and their strength in the face of so much adversity must always be part of the Zionist epic as we go on to new challenges and try to learn the lessons of this particular defeat.

One hopes at least that they take comfort in the tears of the soldiers who came to evict them and in the outpouring of support from around the country. Perhaps in the encounter between the soldiers and the settlers — such as those who danced together in Atzmona — and in the tears of young men and women called on to undertake such a sad task, there will be rekindled a sense that we are all one people, with one fate, sharing together this tear-stained land.

It will take some time to understand the lessons of Gaza and northern Shomron and to find a way to prevent this episode from becoming some kind of turning point, leading as some have said to an inevitable decline and perhaps failure of the whole Zionist enterprise. We can be fairly certain that had 80,000 Jews moved to the Gaza coast instead of only 8,000, they would probably be there forever. There is strength in numbers and perhaps even permanence.

The settlement movement had several decades in which it could have inspired the youth, young families and even veteran families to live the Zionist dream beyond the old boundaries, just as after World War I the Zionist movement had nearly two decades in which it might have persuaded European Jewry to leave Europe before the gates were locked and the destruction began.

Somehow inspiration failed and not only was there pitifully insufficient settlement, but the hearts and imagination of Tel Aviv and Kfar Saba and even nearby Ashkelon, Ashdod and Beersheva never were inspired by the rightness and justice of the idea. There is still time to correct this failure, lest Gaza becomes an example not of how hard it is to uproot, but of how possible it is.

Ben Dansker is a partner in the Jerusalem-based consulting firm Atid EDI. He lives in Efrat in the West Bank.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

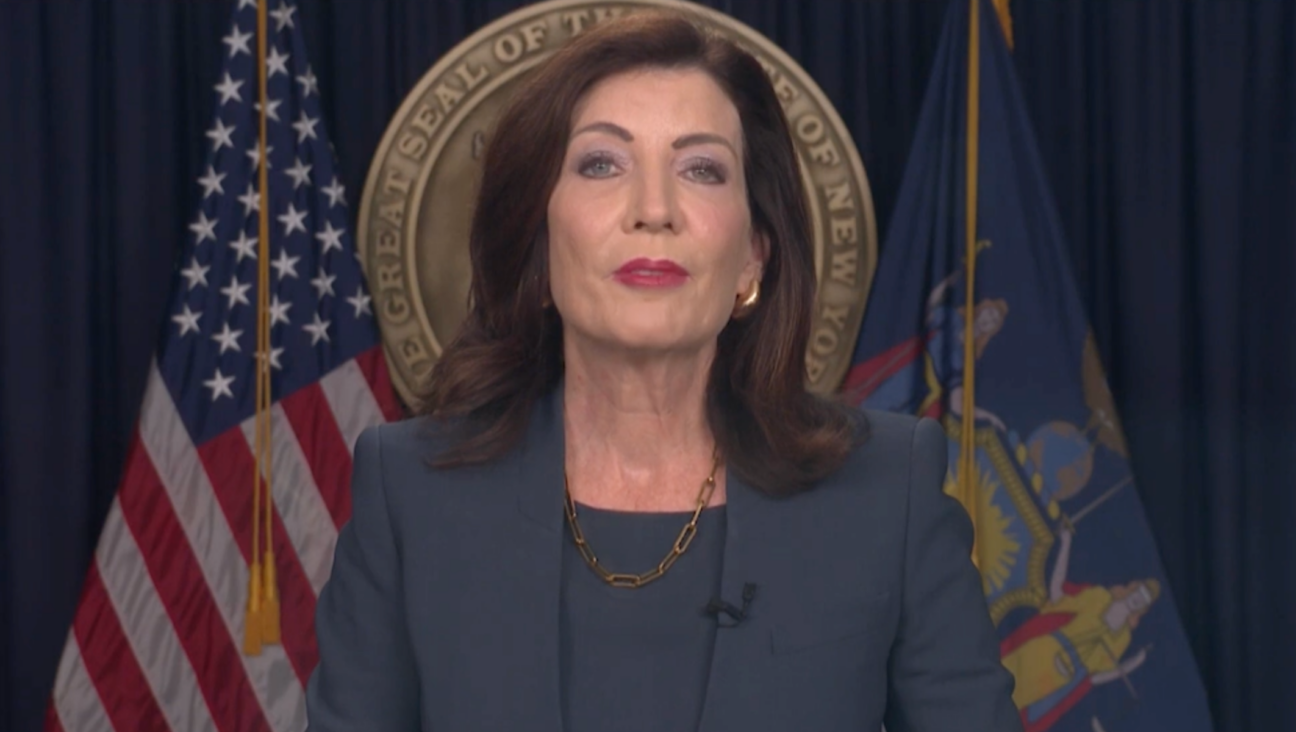

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward In first Sunday address, Pope Leo XIV calls for ceasefire in Gaza, release of hostages

-

Fast Forward Huckabee denies rift between Netanyahu and Trump as US actions in Middle East appear to leave out Israel

-

Fast Forward Federal security grants to synagogues are resuming after two-month Trump freeze

-

Fast Forward NY state budget weakens yeshiva oversight in blow to secular education advocates

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.