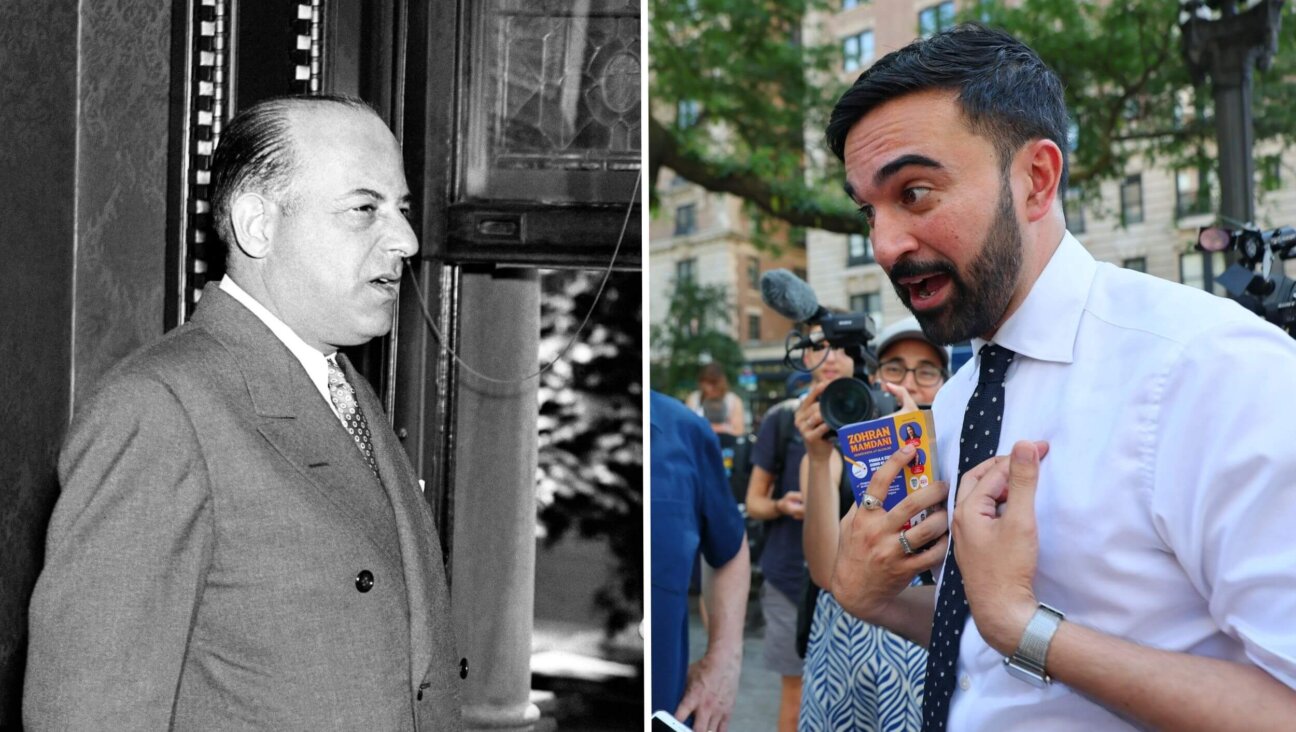

David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s Segregationist Founder

Image by Getty Images

‘The danger we face is that the great majority of those children whose parents did not receive an education for generations will descend to the level of Arab children,” Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, declared at a July 1962 meeting. He was speaking with the head of a teachers federation on the question of whether to segregate “Mizrahi” children, whose parents came from Muslim countries, from “Ashkenazi” children in school.

In the document from the Labor Party archives, revealed recently in Haaretz, a shocking image is conjured up. Did Israel’s first leader really consider segregating Jewish children according to country of origin? Why did he use racially tinged terms of abuse, worrying that Israel would become “Levantine” and “descend” to be “like the Arabs”?

The document is emblematic of a tragic Israeli problem, the legacy of the disastrous policies put in place in the early years of the state that at the time seemed in line with prevailing European concepts but did irreparable harm.

Consider the case revealed on April 9 by author Orna Akad at the blog +972. She related how 23 years ago she went to a workshop at the community of Neve Shalom. “One of the participants in the workshop was also a member of the community’s admission committee… we came up to her full of hope and said proudly that we are a couple, a Jewish woman and an Arab man, and that we would like to register and appear before the community’s admission committee,” Akad said. The woman had bad news: “We are a community which encourages life together in coexistence, but we are opposed to mixed marriage.”

If you are perplexed, you should be. Israel’s small communities have an unusual way of organizing themselves. An “acceptance” or admissions committee regulates almost every single community outside a major town. You can’t just move to a place, you have to ask to be admitted. It is why a May 2012 headline screamed, “Sderot activists win right to move to Kibbutz Gevim.” They didn’t want to be kibbutz members, just to live in an expansion area of the kibbutz. But one committee member had blocked them, reportedly saying, “We are trying to introduce new blood into the community, but new blood needs to match what is already there.” The newcomers were not “attuned to community life.”

How did some 1,000 communities in Israel become gated communities, so that people who are Arab, Ethiopian or other minorities can be denied the right to live where they want either directly or as result of euphemistic rulings like that they are “not attuned to community”? This is one of the main legacies of 1950s Israel.

Admissions committees created ethnically homogenous Jewish communities (Yemenites in one place, Hungarians in another). Worse, a segregated education system for Jews and Arabs cemented total separation so that 99% of pupils study in either Jewish or Arab schools through the end of high school. The education system was put in place in 1949, but it should have been obvious that “separate development” was a road to future disaster.

David Ben-Gurion is often portrayed as a mythical formative figure in the early years of the Jewish state. In Anita Shapira’s 2014 biography she lionizes him: “He knew how to create and exploit the circumstances that made its [Israel’s] birth possible.” Peter Beinart similarly paints a picture of early Israel endowed with liberal and socialist principles. “Labor Zionists insisted that the character of Jewish life in Palestine, and of the eventual Jewish state, was as important as the state itself.” The well-known author Ari Shavit wrote in his book, “My Promised Land,” that “the newborn state [of Israel] was one of the most egalitarian democracies in the world.” Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen romanticized Israel’s early years as “fighting intellectuals, rifle in one hand and a volume of Kierkegaard in the other.”

There is a massive nostalgia and a total misunderstanding of the nature of the state in those years. Israel was not egalitarian in the 1950s; it was a divided society, in which Arab citizens, having watched the vast majority of their community flee or be expelled from the country in 1948, were kept under military-imposed curfew. It was a society in which security concerns trumped civil rights, in which nationalistic military parades were common, and ethnic and religious divisions were cemented.

The founders of the state saw themselves as embarking on a massive social engineering experiment. As these new documents reveal, Ben-Gurion imagined that the Jews who had come from Arab countries would soon outnumber Jews of European origin — “In another 10-15 years they will be the nation, and we will become a Levantine nation, [unless] with a deliberate effort we raise them…” he said. The country had a responsibility to elevate this population from its many generations of living in, as he disparagingly put it “downtrodden, backward countries.” The disdain for Arab culture was extreme, despite the fact that Arabs in British Mandatory Palestine held high positions, were the intellectual elite of the country and had a sophisticated society.

The discrimination of the 1950s haunts Israel today. It persists in the media, as when Tel Aviv’s Ashkenazi elite is referred to as a “white tribe,” or when Russian immigrants are mocked as having “crime in their blood” and a successful Arab citizen like TV host Lucy Aharish is described in one article as not “dressing like an Arab.” The segregated schools and admissions committees created a balkanized society. Rather than romanticizing the leader who perpetuated these divisions, people should imagine an Israel in the future that reforms the failed legacy. Reduce segregation and encourage diverse communities. Interrogate the past, don’t whitewash it.

Seth J. Frantzman is the opinion editor of The Jerusalem Post.