The Supreme Court’s New Ruling About A Playground May Save Your Life

Image by getty images

On Monday, the Supreme Court struck down a Missouri law that prohibited any state government funding to religious institutions. The decision, in effect, prevents the government from singling out religious institutions for worse treatment based upon their religious status. And, maybe more importantly, it reaffirms the right of every religious institution to receive funds for the safety and security of their members—a right of increasing importance given the growing specter of anti-religious violence in the United States, especially against Muslims and Jews.

The particulars of the case—Trinity Lutheran Church v. Comer—were, in many ways, mundane. The church operates a preschool with a playground on its premises. In 2012, it applied for a state grant that provides funds to make play areas safer for children. The church qualified for the grant, but was denied the money because the Missouri state constitution prohibits public funds from being given to a religious institution under any circumstances.

The church sued, arguing that this exclusion constituted a prohibited form of religious discrimination. The state countered that it had the right to exclude religious institutions from public funding because it did so in service of another core constitutional principle: the separation of church and state. Importantly, both parties agreed that the U.S. Constitution allowed Missouri to give the church money for a non-religious use, like resurfacing a playground.

But Missouri contended that it should be permitted to have a law that keeps church and state even more separate than required by the First Amendment. Indeed, more than 50% of states have such laws that prohibit government funds being granted to religious institutions.

Missouri’s argument thereby raised the following question: when states keep church and state more separate than constitutionally required, is that permissible, because it is in service of a legitimate constitutional principle, or is it a prohibited form of religious discrimination, because it unnecessarily excludes religious institutions from government funding?

The Court’s decision in favor of Trinity Lutheran Church held the latter. According to the Court, excluding the preschool “expressly discriminates against otherwise eligible recipients” because it “disqualif[ies] them from a public benefit solely because of their religious character.” Of course, the Court’s opinion indicates that had the money been for a religious activity, the outcome would have been different; indeed, to provide a religious institution with funding for a religious activity would be constitutionally prohibited under Establishment Clause principles of separation of church and state. But where the money is going for something neutral—like resurfacing a playground or, more generally, providing for the safety and security of religious institutions—there is no constitutional prohibition. And, therefore, for states to exclude religious institutions from such government benefits is both discriminatory and dangerous.

Some Jewish groups have expressed concerns about the Supreme Court’s opinion, arguing that we are on a slippery slope to the government directly funding religious activity. For example, the CEO of the Anti-Defamation League, Jonathan Greenblatt, issued a press release where he worried that the Court’s opinion represented a “disturbing step back from th[e] commitment” of “[m]aintaining the separation between church and state.” And one can understand why the transfer of funds from government to a church-operated school might serve as a red flag given the importance of keeping some degree of separation between church and state.

But the reality is that an opinion against Trinity Lutheran would have been out of line with our core constitutional commitments animating the relationship between church and state. It simply cannot be the case that an institution, because of its religious character, can be excluded from essential government funding to protect its members. Missouri’s law, which required that “no money shall ever be taken” from the state and granted “directly or indirectly” to any religious institution, would—if taken at its word—prohibit government from providing financial support to religious institutions affected by a natural disaster or to provide for increased security in the wake of violent threats, even if such funding were readily available to all other secular institutions. The religious character of an institution cannot be used by the state as a reason to expose its members to unnecessary dangers.

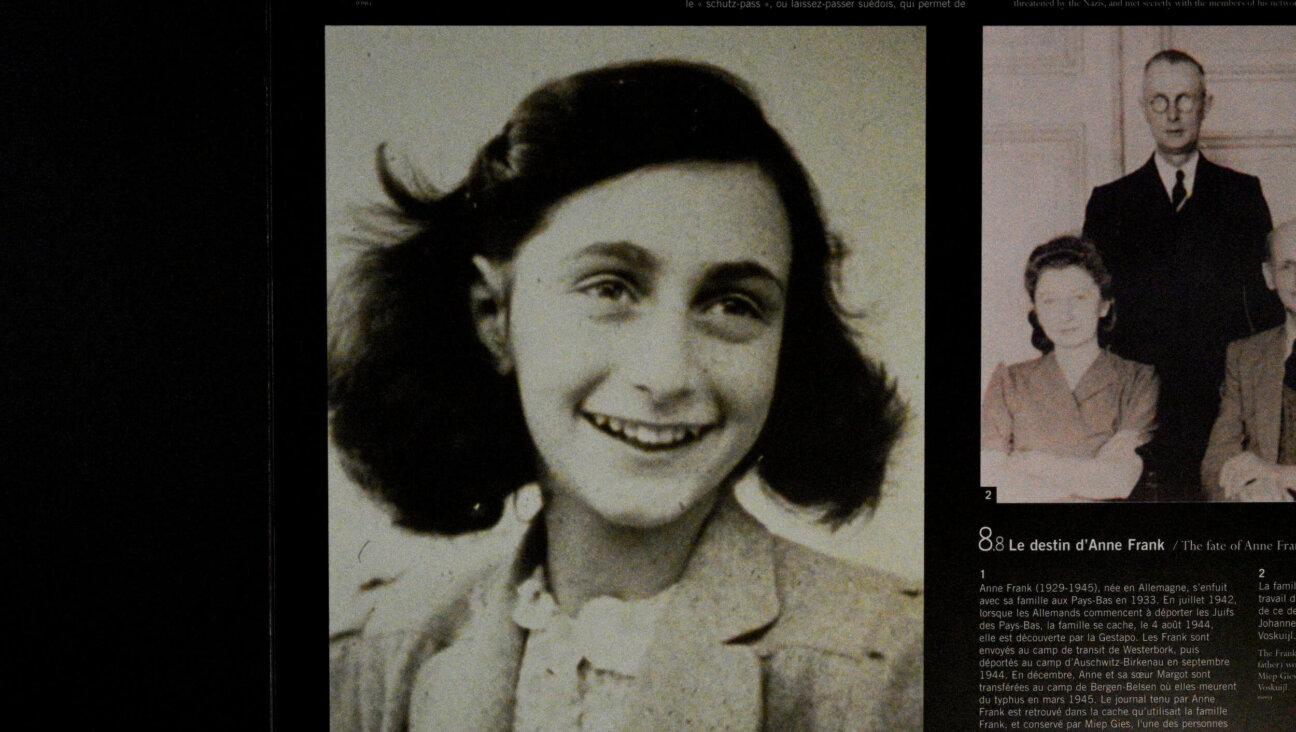

This commitment to ensuring that government provides religious institutions with the resources they need to protect themselves is of particular importance at this juncture. According to a 2016 FBI report, religiously-motivated attacks against Jews – already by far the most-targeted American religious group – grew 9% from 2014 to 2015. The statistics were even worse for Muslims: attacks against them jumped 67%. And with recent events in London and elsewhere, concern about even more carryover of anti-Muslim violence looms large in the United States. The notion that states could maintain laws that would prohibit vulnerable religious institutions from receiving any kind of government funding for their own protection is ultimately unconscionable.

The Supreme Court opinion does not represent a constitutional retreat on principles of separation of church and state. Ultimately, the Court’s decision ensures that states continue, in line with the demands of the federal constitution, to withhold government funds from religious activities. But the opinion also makes sure that religious institutions cannot be singled out or excluded because of their religious status and character, especially when citizens need the government’s protection. Excessive exuberance for the separation of church and state cannot be allowed to boil over into religious discrimination.

Michael A. Helfand is an associate professor at Pepperdine University School of Law and Contributor at The American Project at Pepperdine School of Public Policy. He filed an amicus brief (along with Nathan Diament) on behalf of the Orthodox Union supporting Trinity Lutheran Church.