Don’t Appropriate Anti-Semitism. Jews Are More Than Our Suffering

Image by Getty Images

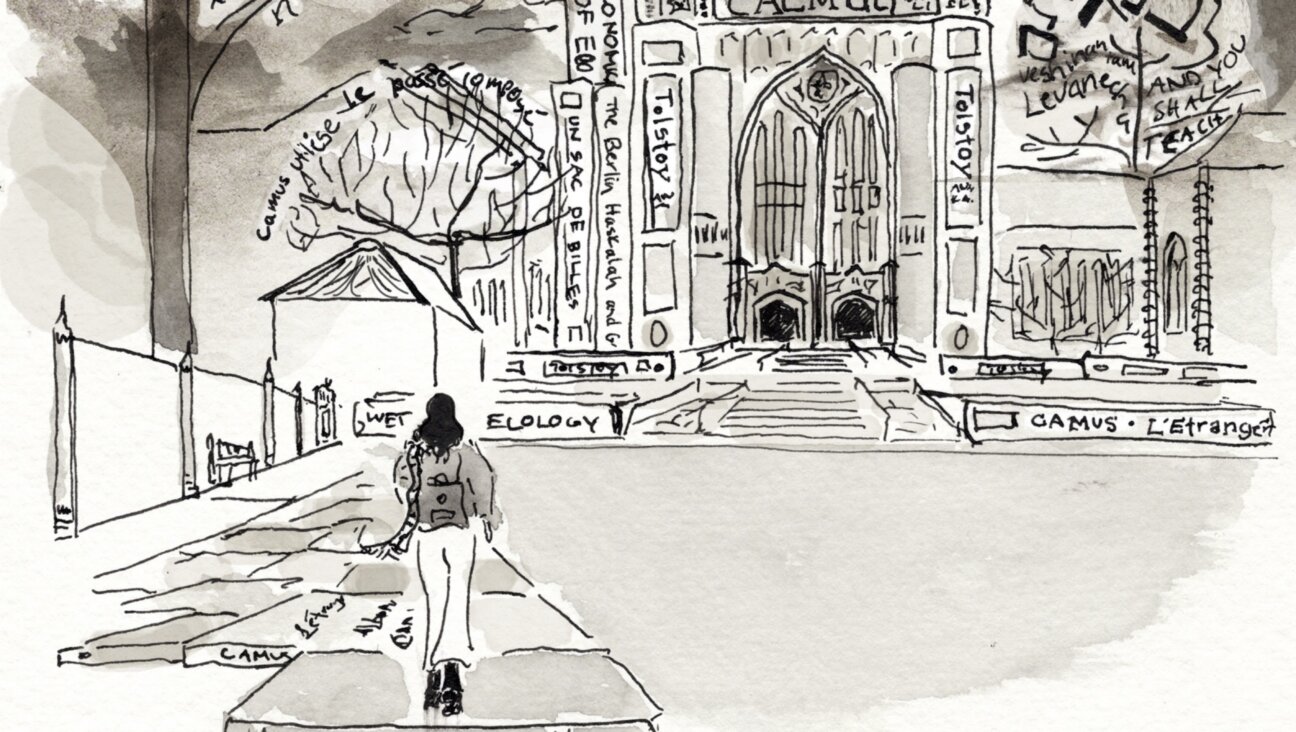

Decades after Holocaust, European intellectuals, some of them Jewish, began writing books and articles investigating the European history of ideas which led to fascism and, ultimately, to the concentration camps. Many of these intellectuals, prominent philosophers and critical theorists like Jean-Francois Lyotard, began using “the jew” as a trope or concept (indicated here with the lower case). For them, “the jew” describes not the Jewish people per se, but rather any minority group scapegoated by the majority culture. Typically, “the jew” is powerless and homeless; Jews are transient, aliens against whom nationalists and populists define themselves. “Anti-fascism,” French writer Alain Finkielkraut writes, “had established the Jew as a value: as the gold standard of oppression, as the paradigm of the victim.”

As the recent article in the The Forward demonstrates, universalizing Jewish persecution to talk about “the jew” is still very much in vogue.

Borrowing from Zygmant Bauman, Helene Meyers argues that former presidential candidate Hillary Clinton is being subjected to anti-Semitism because she is a “jew,” a victim, in her case, of malicious political rhetoric. Since Jewishness has been universalized into a concept of victimhood, anti-Semitism can be directed at non-Jews like Clinton. The article recites some of the rhetoric leveled at Clinton from across the political spectrum to suggest that the former Secretary of State is our national “scapegoat,” or our conceptual jew.

That Hillary Clinton — ex-Secretary of State, former Senator, and current multi-millionaire who won 65.8 million votes in the 2016 presidential election — inhabits the position of “the jew” reveals the absurdity of turning Jews into a concept.

The problem with conceptualizing Jewishness, especially when the concept refers only to a troubled history of Jewish persecution, is that it robs the community of its own agency. When Jews become a universalized concept, we lose, among other things, the ability to talk about anti-Semitism with any specificity. Anti-Semitism becomes nothing more than an allegory for universal suffering.

Elie Wiesel wrote about the tendency to universalize Jewish suffering. Expounding upon what he called “the most vicious and injurious” anti-Semitism, he argues that anti-Semites “assault the memory Jews hold of their own past suffering,” typically with statements like, “others suffered, too” or “others have been made to suffer by the Jews.” Such efforts attempt to “de-Judaize” Jewish experience, making it impossible to talk about Jewish suffering.

Conceptualizing Jewishness and Jewish suffering de-Judaizes our experiences for the sake of comparison, making Jewish suffering a universal injustice as opposed to an injustice perpetrated against Jews. Occasionally this conceptualization might be well-intended, but no other group’s suffering seems to serve so frequently as a universal concept. The 2016 presidential election saw unprecedented anti-Semitism in the American political sphere, much of which stemmed from the so-called alt-right. The last decade has also witnessed an alarming increase in progressive anti-Semitism, particularly on college campuses. According to the Anti-Defamation League, there has been a 67% increase in anti-Semitic incidents in the US in the first three quarters of 2017.

That Hillary Clinton was subjected to unacceptable and misogynistic rhetoric by President Donald Trump is inarguable. But Meyers conflates all political rhetoric used against Clinton in order to claim that Clinton was subject to anti-Semitic language. Donald Trump, Sebastian Gorka, Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and Donna Brazile are each referenced as contributing to attacks reminiscent of anti-Semitism that Clinton has dealt with since the presidential campaign.

When everyone who is victimized can lay claim to experiences akin to anti-Semitism, we lose the language to talk about our community’s particular concerns. Even worse, “Jewishness” becomes defined as nothing more than perfect victimhood.

Emmanuel Levinas, a Jewish philosopher who conceptualized Judaism but not Jews, once said to a Catholic priest, “we reject, as you know, the honor of being a relic.” So too we should refuse the honor of being a concept. We are not ourselves defined by our victimhood, and we should certainly reject anyone else’s attempt to define themselves by our tragedies.

Anti-semitism is resurgent in the United States, and it has infected the left as well as the right. If there is a Jewish scapegoat, it is not Hillary Clinton. It is us.

Brandon Katzir is a writer and an Assistant Professor of English at Oklahoma City University.