Leviticus 18: Don’t Shy Away From Wrestling With The Torah’s Tough Texts

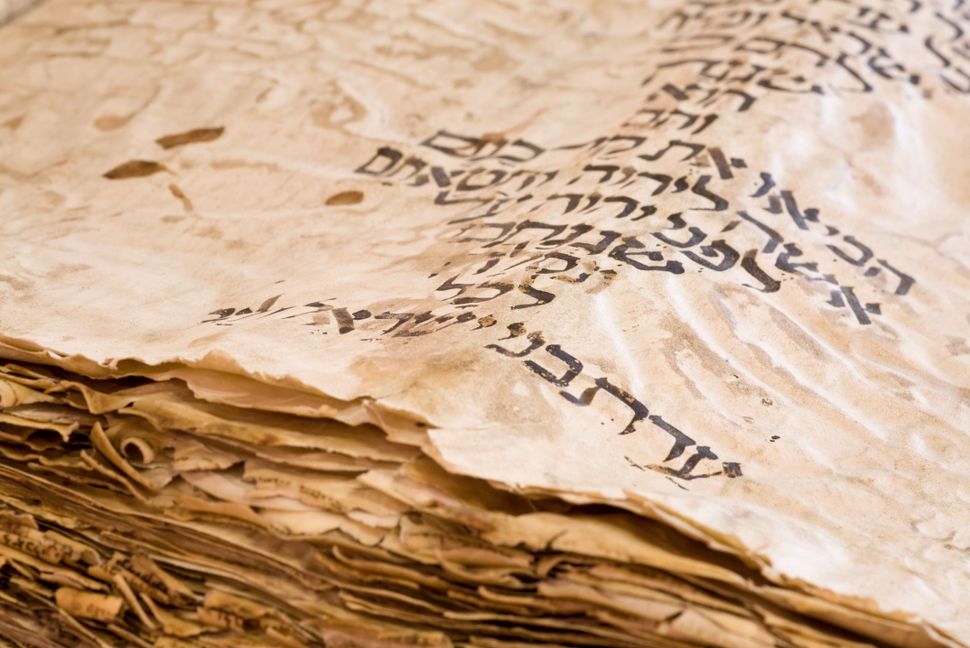

Image by Arpad Benedek/istockphoto

In most traditional synagogues in the United States, the Torah reading for Yom Kippur afternoon is Leviticus 18, a chapter that speaks about sexual sins, supposedly committed by the inhabitants of Canaan, that we Jews should avoid.

For generations, the Reform Movement—and, more recently, many Conservative congregations— have chosen to read instead Leviticus 19, which outlines ways to be holy. It’s like a greatest hits of Jewish ethical mandates: love your neighbor as yourself, avoid bribes, do not insult the deaf, and don’t stand idly by the blood of our neighbor.

This year, our congregation, Temple Ner Tamid in Bloomfield, N.J., went rogue and returned to the traditional reading.

I decided to do this after a conversation with a group of teenagers who expressed frustration that their education only included the easy stories and teachings of Judaism. They asked to spend time confronting challenging parts of our tradition, things that might make them uncomfortable.

After discussing different ways that modern, liberal Jews have wrestled with Leviticus 18— especially verse 22, which reads, according to the Jewish Publication Society translation, “Do not lie with a male as one lies with a woman; it is an abhorrence” — the teenagers asked why we don’t read it on Yom Kippur. I explained that Ner Tamid, like many if not most Reform congregations, read the chapter when it comes up organically, in the yearly cycle, but not again during the High Holy Days, instead choosing the affirmative message of the later chapter.

Quickly, the kids pushed back. They believed that the High Holy Days were precisely the time to read the tough text. Yom Kippur is the time when the most congregants attend services, they pointed out, adding that the holiday’s theme of self-reflection should leave us uniquely positioned to unpack and wrestle with difficult ideas. We decided to try it.

First we had to make photocopies: so rare is it for Reform synagogues to read Leviticus 18 on Yom Kippur, the text was not even in our Machzor, Mishkan Hanefesh. That was easy enough.

The bigger challenge was figuring out how to publicly wrestle. As one gay-rights activist in our congregation told me, the line is triggering for many in LBGTQ+ community because it has so often been weaponized against them.

We decided that the way to deal with a line that silences so many is to amplify their voices. We formed a panel of LGBTQ+ members to respond to the text: a man married to another man who has three young daughters and serves on our board; a Baby Boomer who, with her now-wife, was the plaintiff in the landmark 1993 case that legalized second-parent adoption in New Jersey; and a 14-year-old who recently adopted a new name.

Each brought a distinct perspective to the conversation. One spoke about the tension of weighing our ethics against that of an ancient system. Another cited modern rabbis who deconstructed the actual text, noting that the Hebrew word used in verse 22 for “to lay with” is often associated with violence or abuse, suggesting the text prohibits unsafe uses of sex to wield power, not consensual same-sex relationships. Perhaps the most moving thoughts came from our youngest panelist, who said that despite the discomfort that the text brought, we should read it, because we will get something out of the wrestling.

As I listened to this statement, I thought about how the Talmud handles the Torah’s teaching that the insolent and rebellious son should be taken out to the public square and stoned to death. Feeling uncomfortable with this, our ancient rabbis interpreted it out of existence, putting so many strictures on who might be considered insolent or rebellious that they decided, “never has there been and never will there be” such a case of stoning one’s child. However, they said, just because the case is now hypothetical does not mean we should ignore it.

“Why then was the law written?” they ask in Sanhedrin 71a. “That you may study it and receive reward.”

For our sages, reward often meant heavenly merit and a place in the hereafter. For us, the reward of wrestling with problematic texts is here and now.

Over the course of our conversation, I watched congregants who were not part of the LGBTQ+ community become sensitized to how problematic this line is for their neighbors and friends. I saw the text become a catalyst for galvanizing change – people who were bothered by the latest Supreme Court employment-discrimination cases left with a renewed vigor to act. I noticed that as people struggled with the text, it became a model for how we might confront other challenging piece of our tradition: chosenness, depictions of a jealous God, violence in the Torah.

I left understanding what it meant to members of my community who identified as part of the LBGTQ community to be seen, liturgically, in a way far different than they are when a rainbow flag hangs outside of our synagogue during Pride month.

I think we will continue to read Leviticus 18 on Yom Kippur. It won’t be every year, and it won’t always be in the same way. But when the zeitgeist calls out for it, when we need a reminder of how far we still have to go to include all members of our community, we will return to the text.

Every piece of our Jewish tradition is a catalyst for holiness, even the hardest parts, the most uncomfortable pieces. I hope more Reform and Conservative synagogues will consider thoughtfully reading Leviticus 18, and giving it the mindful and passionate wrestling it deserves.

Rabbi Marc Katz of Temple Ner Tamid in Bloomfield, N.J., is the author of The Heart of Loneliness: How Jewish Wisdom Can Help You Cope and Find Comfort.