Before he died, he recorded songs and stories for his future grandchildren

A father’s final gift: ‘The Wheels on the Bus’ and Dr. Seuss

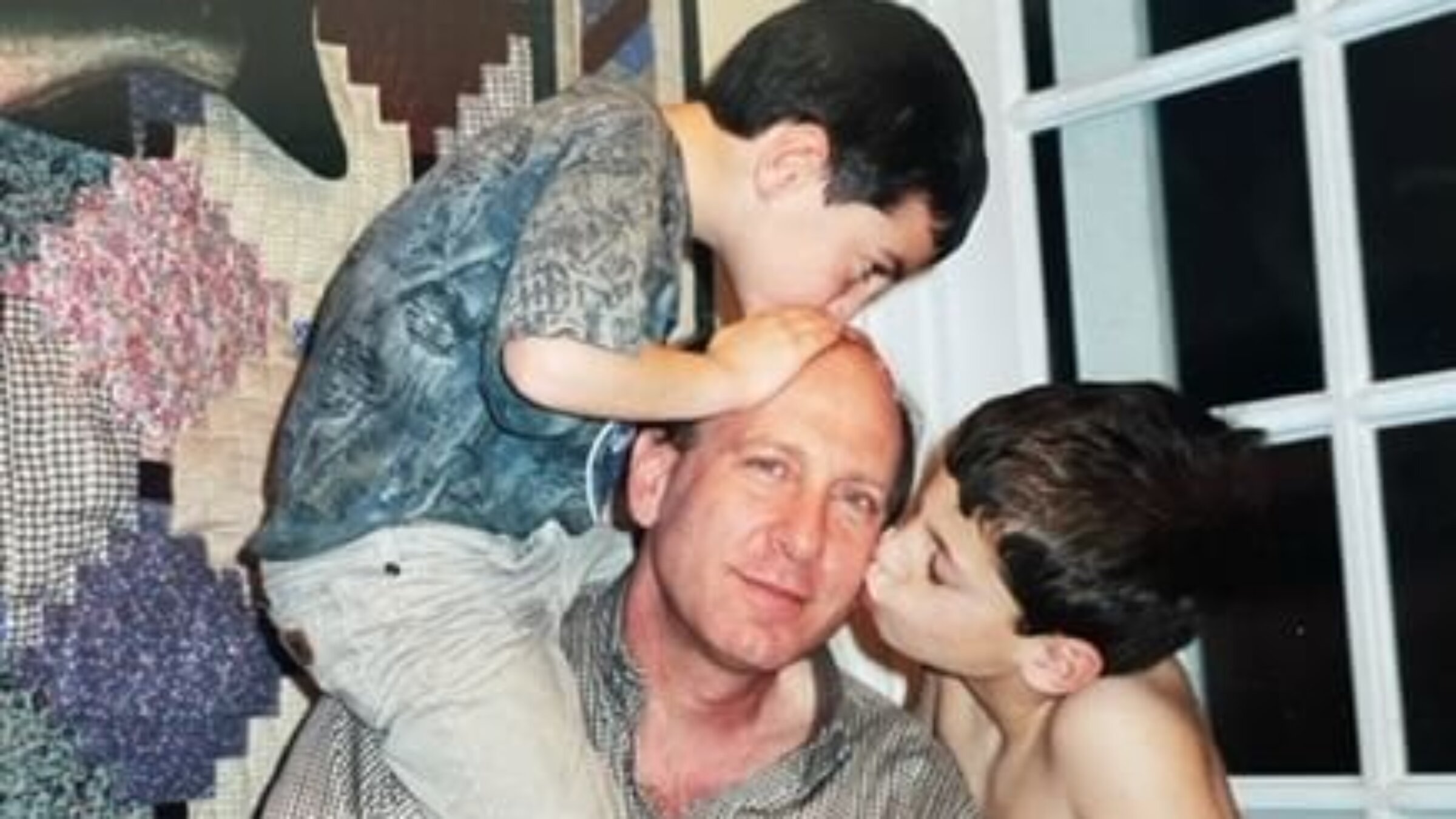

Elliot Sturman with Daniel, left, and Joshua. Courtesy of Ann Sturman

It was September of 2019 when Elliot Sturman reached out to me with the news that he had brain cancer.

A number of years earlier, I had conducted oral histories with Elliot’s mother and uncles, as part of my business helping people record their life stories. Now Elliot, at 63, wanted to discuss his legacy.

“I probably have about a year to live, so I sort of need to get on this.” he said. “I want you to help me share my own lifetime memories, and also record me reading my sons’ favorite childhood books.”

I’ve helped hundreds of people, including many with terminal diseases, save their personal and family histories, but Elliot’s plan to read his children’s books was a first. His sons, Joshua and Daniel, were both already in their 20s, and the idea was to create something for the future grandchildren he’d never get to meet.

“One of my favorite things to do with my dad when I was a little kid was him reading to us, and I wanted to somehow be able to give my own children that experience with him,” explained Daniel, an engineer who lives in Northern California. “It was also about me being able to relive that myself.”

Elliot, who worked in human resources and also taught b’nai mitzvah students to lay tefillin and ran scholar-in-residence weekends at Temple Etz Chaim in Thousand Oaks, California, loved the idea. Growing up, he had always wondered about Jacob Mitzman, the relative his own middle name honored — he didn’t even realize that was his mother’s grandfather until he read the memoir I’d helped her compile in 2011.

“I’d seen his picture, and I’d been told that I was named after him, but I never knew anything about him and his life — just that photo seemed insufficient and inadequate.” Elliot said of Jacob. The video, he thought, would ensure that for his own descendants, “I would be more than just a picture on the wall. They’d have a sense of who I was.”

Stage 4 cancer

The illness had hit quickly. Elliot suddenly had difficulty controlling the muscles in his face. The family thought he had suffered a stroke; instead, it was brain cancer, already at stage 4. “His clarity of mind was off,” Daniel recalled, “and he was pretty rapidly deteriorating.”

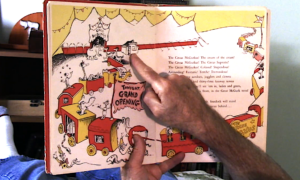

The tumor was surgically removed right away, which allowed him to function relatively normally for about six months. During the course of a few weeks, when Elliot could muster the strength, I recorded over his shoulder as he lay on each of his sons’ childhood beds, reading books by Dr. Seuss and Sandra Boynton along with “Calvin and Hobbes,” “Harold and the Purple Crayon,” and many others. He sang “The Wheels on the Bus” and “Waltzing Matilda” into the camera. I wanted to sing with him, recalling the same tunes and stories from the childhood of my own son, Ben, who is now 31.

As he read, Elliot paused to describe details in the books’ drawings, asking a future grandchild what he or she thought a certain character on the page was doing. He talked about the authors. When he opened Dr. Seuss’ “If I Ran the Circus,” he started at the copyright page. “This book was written in 1956, which is the year that I was born,” Elliot told the camera. “So the book is 63 years old, like I am.”

Daniel recalled him doing the same things years before.

“On every page, Dad would find things to point out,” he explained. “He would pick up on subtle things, like when he read ‘Harold and the Purple Crayon,’ he said, ‘See how the moon has moved across the sky between these two pages, to show the passage of time?’”

Daily gratitude

Daniel smiled through tears, and then shared another memory.

“After we read books at night, we would say the Shema, in Hebrew and in English, and then we would say good night to each other, and then Dad would ask us, ‘What were you grateful for today?’”

Elliot had told his future grandchildren about this ritual, too. “There’s a lot of psychological literature that says that there is a heavy correlation between being grateful about what you have or what you are, and being happy,” he said. Then he looked at the camera and said, “And hopefully, you guys will be happy.”

I had to hold back tears. My time with Elliot was such a mixture of joy and sadness. It was so clear that he wanted to leave behind something more meaningful than money.

Knowing that we’re all going to die, what do we want our lives to be about? How do we want to be remembered? And how do we spend whatever time we have left?

Choosing his legacy

I reached out to Arash Asher, director of a cancer rehabilitation program at the Cedars-Sinai Cancer Institute, for some perspective.

“We should be thinking about our legacy when we’re not facing a life-threatening illness,” he told me. “You can define your own legacy. You can still find meaning in things that are very important to you.

“I’ve found that people who have some sense of legacy are much less likely to be depressed,” Asher continued. “They’re much more likely to do things that are meaningful to them because they know, like we all probably should, that we don’t know when our last day is going to be.”

Rabbi Steve Leder of Wilshire Boulevard Temple in Los Angeles has a new book about legacy, called “For You When I Am Gone: Twelve Essential Questions to Tell a Life Story,” which guides readers to create what Leder calls “an ethical will” to share their most important values with their family.

Rabbi Leder was delighted when I told him about Elliot’s project. “Reading to children at bedtime is one of the most beautiful intimate parenting and grandparenting opportunities given over to humankind,” he noted. “And this will enable his sons, in a sense, to invite their own father into that intimate moment with their future children.”

Communicating love

In 2009, when I was turning 60, I signed up for a yearlong workshop based on another book, by Stephen Levine, called “A Year to Live: How to Live This Year as If It Were Your Last.” We participants were all in good health, but we were instructed to imagine that we had received a terminal diagnosis. How did we want to spend that final year? Who did we want to spend time with? What would we regret not doing?

That year, I took my son, Ben, to the Galapagos Islands. And ever since, I have made sure I tell people I love them rather than assuming they know.

And I’ve been only imagining I had a year left; Elliot was experiencing that reality. He died in July 2020, at 64.

His open and courageous approach to his final chapter allowed him to leave something joyous and meaningful for his family. And it’s not just the video.

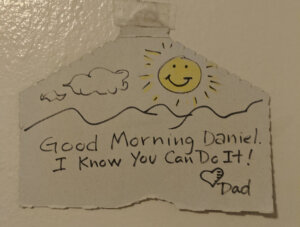

“When I was in high school,” Daniel recalled, “my dad drew me a note on the back of the tear-off cardboard of a Ziploc bag box, and wrote, ‘Good morning Daniel. I know you can do it. Love Dad.’

“I have it framed in my room,” he said, “and it might be the most important thing I own.”

Below is a video compilation of some of Elliot’s readings and reflections.