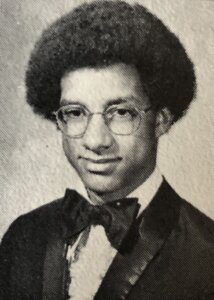

FIRST PERSONThe teenage trauma of being forced to work on Rosh Hashanah — at a shul

Being a ticket-taker at a popular theater was a fun way to spend a summer. But then the High Holidays came. And the manager asked me to rip tickets, not caring that I was Jewish

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The news that some synagogues no longer charge for High Holiday tickets may be welcomed by those uncomfortable with paying to pray, or who simply don’t have extra cash during uncertain economic times.

For me, it comes about a half-century too late, though not for any of those reasons.

In my interracial, interreligious family on Chicago’s Near North Side, I did not have a particularly religious childhood. Yet it was a Jewish one. There were few Jews in our immediate area and no synagogues, so on holidays my mother would take us to the end of the line of the El to a synagogue near the high school where she taught. She knew the rabbi at Temple Beth Israel, but I doubt we ever formally joined the congregation. But because we were only going to children’s services, who cared?

We went less frequently as my brother and I approached our teens. Neither of us had a bar mitzvah on our 13th birthdays, and by the time I was in high school, we stopped going altogether.

So was my Jewish life when, in late summer 1973, I got a job as an usher at the Carnegie Theatre on tony Rush Street. The manager, Jose, ran a very tight ship. The fall came and he scheduled me to work on Rosh Hashanah.

“But I’m Jewish,” I protested.

“Too bad,” I recall his response.

I don’t know if Jose knew it when he scheduled me, but on Rosh Hashanah, the theater owner — who was Jewish — had rented out the space to Central Synagogue South Side Hebrew Congregation. The synagogue needed the theater for its well-attended High Holiday services.

Rosh Hashanah came and I stood at the theater entrance to take tickets. The congregation president, a jovial middle-aged man in a blue suit whose name I think was Manny, arrived to give me instructions.

“All we need you to do,” I recall him explaining, “is to take the tickets and tear them in half, and put them in the box.”

I looked at him and said nothing. He repeated the instructions, adding, “We need you to do this because we can’t tear paper because we’re Jewish.”

“I can’t either,” I replied.

“Why not?” he said.

“Because I’m Jewish, too.”

As an African American Jew, I was used to the “how-can-you-be-Jewish?” bit, even at 16, and would preempt it by volunteering “My mother’s Jewish.” (Anyone asking that question today to me or anyone within my earshot can expect a much sterner response.)

When it sank in, Manny asked, “Why are you working?” I pointed to Jose, who was sulking in his office.

“Oh,” Manny said. This was a problem: The congregation needed the tickets collected, but they couldn’t ask another Jew, subject to the same restrictions they were, to collect them. Manny caucused with a few congregation leaders, and me. I was suddenly one of the gang — of 50-year-old Jewish men!

One of the group went off a little ways and came back.

“OK,” he said. “I just talked to God. He says you can tear the tickets.”

The others didn’t agree and with the congregants beginning to show up, we all took turns taking, and tearing, tickets. It wasn’t ideal but at least we all were sinning together.

Finally, Manny went over to Jose and pleaded with him to call in someone who wasn’t Jewish. Jose complied and 15 minutes later Siddiqi arrived.

I was invited to join the services and called my mother to join me. By Yom Kippur the next week, I was practically a senior member of the congregation. I remember Manny greeting me — for services this time, not work — smiling with his tongue hanging out, like Einstein.

The service was moving but long. I’m sure I dozed a little. As we walked out, the bemusing transition from usher to Jew-distraught-over-ritual to fasting and atonement of Yom Kippur seemed a significant journey — until I noticed the newspaper box on the street. The headline blared that war between Israel and its neighbors had begun.

Our ticket dilemma didn’t seem very important any more.

A version of this story appeared in Minnesota’s Duluth News Tribune.