Does Jared Kushner know it’s almost Yom Kippur?

‘Breaking History’ is long on self-praise and short on atonement

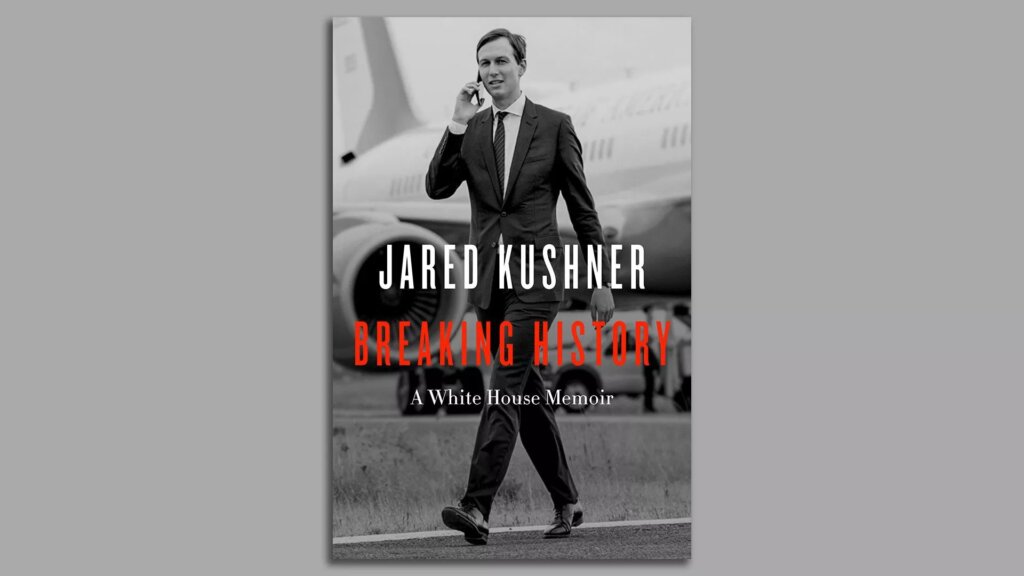

Jared Kushner at Donald Trump’s inauguration. Photo by Getty/Saul Loeb/Pool via Bloomberg

Remember that heart-tugging pop song of 1984, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” It kept popping into my head as I read Jared Kushner’s new memoir.

“Breaking History” tracks Kushner’s time as senior White House advisor under his father-in-law, President Donald Trump. The book has spent five weeks on The New York Times bestseller list, and while there are many White House histories written of those years, none are written by someone who had such personal and professional access to Trump.

Maybe it’s because Yom Kippur is just around the corner and Kushner is well-known to be an observant Jew, but as I read “Breaking History,” I kept looking for moments of what the rabbis call heshbon nefesh, the work we are all tasked to do on this holiday — a moral accounting of our souls, the good the bad, our strengths and weaknesses, our ethical successes and our moral failures.

Spoiler alert: I found none.

Kushner isn’t alone in being unable or unwilling to see, report and account for his failures publicly. I chose to write this column about him, after all, not me.

But, then again, I didn’t serve a president whom 77% of my co-religionists voted against. This data point alone might provoke someone to take a long hard look at where they succeeded and where they fell short.

The former Son-in-Law-in-Chief does the first part well, taking most of the credit for renegotiating the NAFTA agreement and for the Abraham Accords, which publicly codified a not-so-secret, decade-long relationship between Israel and the several Arab states.

But where he and his boss fell short, Kushner deflects. A good example is the Mueller investigation into Trump’s pre-election dealings with Russia.

“Trump was right all along,” he writes. “This whole investigation had been nothing but a witch hunt.”

If Kushner were to give a full accounting, he’d point out that while the report found no collusion, it did find obstruction, and over a dozen administration officials ended up indicted or imprisoned as a result.

Kushner’s reluctance to tell the whole truth is understandable: We all want to be the hero of our own story.

But Yom Kippur comes to teach us there is no hiding from our faults. We fast and pray and dress like the dead, in white. The ancient liturgy cracks open our hearts so that we offer up the whole truth — the good, the bad, the ugly — and we plead for the grace to change and improve.

This requires reckoning with reality as it is, not as we wish it to be. When Kushner meets Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman at the G-20 conference in Buenos Aires, he recalls the ruler “was dealing with the global outcry from the death of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi, who was murdered at the Turkish consulate in Istanbul.”

A reader might get the impression Kushner is actually impressed with the crown prince’s sang froid. But this bloodless account ignores the fact that three years before Kushner wrote his book, the CIA determined bin Sultan was “dealing with the outcry” for a good reason — he was directly involved in Khashoggi’s assassination.

“For the sin which we have committed before You with knowledge and with deceit,” we pray to God on Yom Kippur. Writing about Khashoggi, Kushner manages a doubleheader, sinning with both knowledge and deceit.

Yom Kippur itself only makes one appearance in Kushner’s memoir, and it’s a telling one.

The 2020 presidential debate fell on “the day after Yom Kippur, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar,” Kushner writes, so he was unable to coach Trump. The historian Victor Davis Hanson stepped in, warning Trump, “It’s going to be a lot tougher to debate against a guy like Joe than you think. He’s potentially senile.”

Kushner is ostensibly quoting Hanson here, but the statement Kushner chose to highlight is far from proven, and it’s defamatory. As we read on Yom Kippur, “And for the sin which we have committed before You by evil talk about another.”

On Yom Kippur, we are called out for our inaction, too. In at least two instances, Kushner ignores instances where Trump acted, and Kushner apparently did nothing.

Writing about the COVID-19 pandemic, Kushner takes credit for speeding up the development of vaccines, but leaves out the thousands of unnecessary deaths that resulted, according to the Lancet, from Trump not taking the pandemic seriously enough to begin with.

Writing about the last days of the Trump administration, Kushner described a note Trump left in the Oval Office desk for incoming President Joe Biden as “gracious and from the heart.” But Kushner ignores the evidence that Trump goaded rioters and engaged in a concerted effort to undermine the 2020 election results.

What we choose to highlight when telling others — or God — about our lives is often a revelation of our values. Do you take credit for what went right and blame others for what went wrong — or ignore it altogether? Do you turn a blind eye to wrongdoing? Are you mostly kind, but sometimes callous and cruel?

The answers to these questions can be unpleasant, but important if you want to change and grow.

“Breaking History” doesn’t wrestle with them, which these days makes me wonder: Does Jared Kushner know it’s almost Yom Kippur?