FDR’s broken promise: The Allies defeated the Axis powers in Africa — but the concentration camps stayed open

Operation Torch helped topple the Axis powers and Nazi-controlled Vichy regime, but local Jews and Muslims continued to suffer

American Generals George Patton and Dwight Eisenhower planning Operation Torch, the invasion of Africa, 1942. Photo by MPI/Getty Images

Eighty years ago today, 107,000 American and British troops triumphed over the Axis powers in North Africa, ending the regime’s cruel antisemitic laws.

The weeklong campaign, known as Operation Torch, toppled the hold of the Nazi-aligned French government that controlled Morocco and Algeria. This opened a crucial front of war, allowing the Allies to make their way eastward across North Africa and, ultimately, into Europe via Italy.

To the extent that this military campaign has been understood, it has been through the perspective of the Allied forces themselves. The North African stories of war have scarcely been told.

For 10 years, we’ve been working to change that. We have been gathering the voices of those who survived wartime in North and West Africa, and whose lives were forever changed by the campaign.

Then, as in today’s Ukraine, war was an intimate affair, experienced through hunger, violence, environmental devastation, sexual abuse and a shift in how people viewed their future and their world.

Their arrival was a miracle

As with D-Day in Western Europe, Operation Torch was a turning point for everyone in North Africa, not just Jews. Fascist hate and violence victimized North African Jews and Muslims, Jewish and Christian refugees from Europe, as well as West Africans.

Ait Ali Driss, a Muslim Amazigh bus driver, remembers Jewish and Muslim women ululating in celebration as military jeeps full of American soldiers drove through Casablanca’s central square. Jewish residents celebrated the miracle of the Allied victory over the French fascist regime in front of the synagogues, just a few meters away from Casablanca’s landmark clock tower.

Three days of bombardment had shaken the feeble foundations of homes in Casablanca’s walled city, a neighborhood that overlooked what was then the biggest port of the northern Atlantic. With the end of this historic battle, the local population was overcome with relief. The Vichy and Nazi regimes had some Muslim supporters in North Africa, but most welcomed an end to fascist occupation, famine and war.

Many North African Jews, like those in Casablanca’s Place de France, also welcomed the Allied troops with (literal) open arms, gathering on the streets to welcome them with song and dance.

Sidney Chriqui, a Moroccan Jew, recalls viewing the Allied landing from his window which looked out onto Casablanca’s waterfront. When Anglo-American soldiers came ashore, the young man was astounded to meet Black Americans for the first time.

Soon, he was working for the American military as a translator and interpreter. Jews in North Africa had long served foreign regimes as employees (partly because they were more likely to be multilingual), and sometimes received legal protection because of their service. Chriqui followed in this long tradition, and was awarded a visa to the United States for his efforts.

The Tunisian Jewish composer and musician Simon di Yacoub Cohen wrote a popular song, “Khamous Zana,” that heralded the arrival of the Allies as a bride approaching her betrothed. The song is still sung by Jews of Tunisian descent.

The legendary Moroccan musician Houcine Slaoui had a more skeptical take. His famous song “Lmirikan” (the Americans) presented Moroccan women as gullible dupes of American consumerism seduced by novel treats like cosmetics, chewing gum and candy. It was a misogynist take, but had an important underlying point: American and British troops became the new power brokers in North Africa, at a time when it wasn’t yet clear who would fill the power vacuum left by war.

The suffering continued

After Operation Torch, President Franklin D. Roosevelt vowed to purge the Vichy presence in North Africa, and to liberate the thousands of prisoners who languished in dozens of internment, concentration and forced labor camps in Morocco and Algeria.

These camps held a tremendously diverse prisoner population. Local Jews and Muslims, European refugees (Jewish and Christian), and a wide array of perceived “undesirables” — enemies of Vichy France — were held there.

Rather than immediately dismantle these camps, Great Britain and the United States signed a power-sharing agreement with the French Vichy leadership on Nov. 10, 1942. Admiral Jean Francois Darlan remained in power, and the camps remained in place.

During these post-Operation Torch years, camp prisoners were overseen by the same sadistic overseers who had overseen them during the war. Despite widespread protests, the inhumane camp system existed for years. As in Europe, where traumatized Holocaust survivors lingered in Displaced Persons camps, in North Africa, the postwar era was still a time of de facto internment for many.

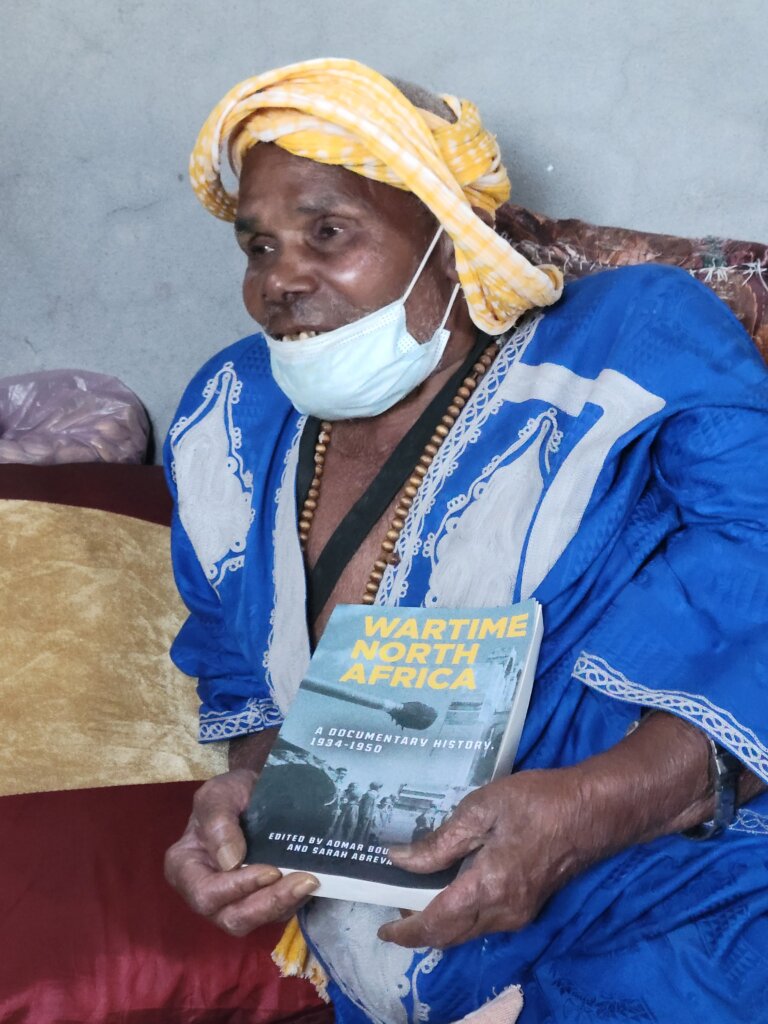

Al-husin Al-gedari, a native of Morocco’s Anti-Atlas mountains who is now in his 10th decade, said that on the North African homefront, children, women and men struggled to survive famine and malnutrition. Some of this devastation was brought on by the French Vichy regime, which redirected food from North Africa to continental France during World War II. But in his memory, Operation Torch threatened the local food supply even further.

The arrival of so many soldiers, combined with the demands of existing European settlers, meant that foreigners’ hunger continued to be prioritized over the hunger of native Jews and Muslims.

Local Muslims and Jews suffered the effects of the war and its tumultuous end. They experienced Operation Torch as a force of liberation and opportunity, but also as a perpetuation of their hunger, imprisonment and vulnerability.

It has taken historians eight decades to listen to local accounts of wartime North Africa. As we remember the campaign that ended the war in this region, we would do well to remember that the pain of global conflicts lingers locally, complicating the very meaning of victory.

To contact the authors, email [email protected].