What makes a ‘Jewish’ politician?

From Jewish summer camp to the struggle for Soviet Jewry, Zev Yaroslavsky’s new memoir describes the experiences that shaped his values

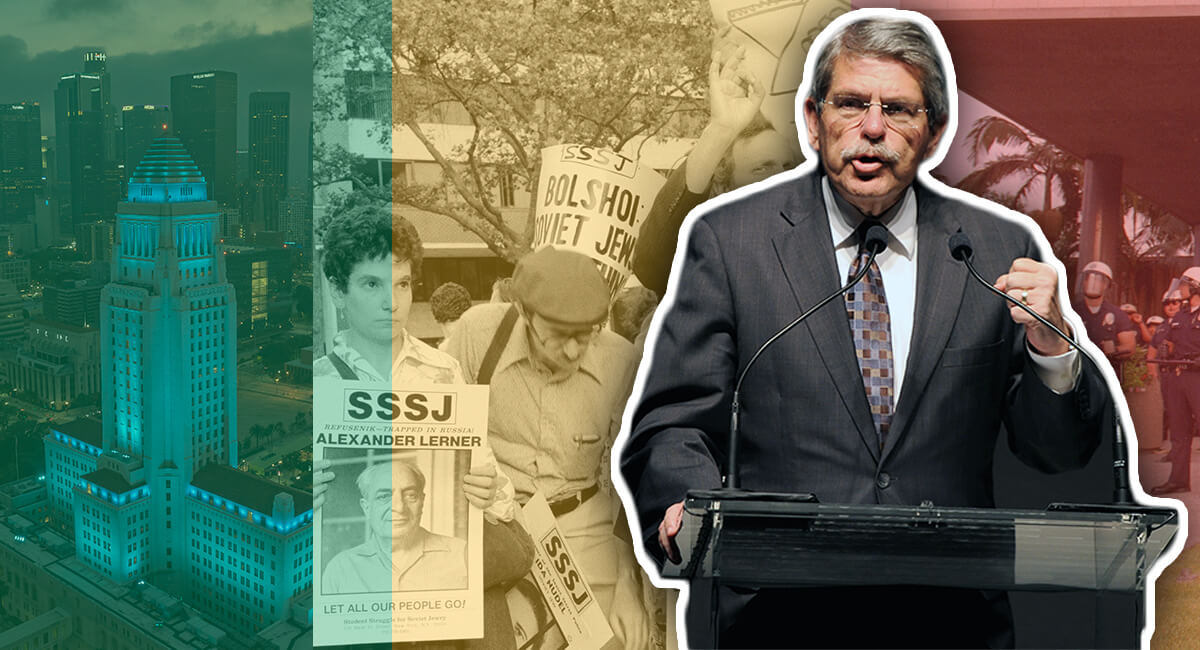

Left to right: LA City Hall, Riots for Soviet Jewry, and Rodney King Riots, and Zev Yaroslavsky. Photo by Getty Images / Forward Montage

The Los Angeles Police Department once planted rumors that City Council member Zev Yaroslavsky regularly paid prostitutes $300 for oral sex.

On the eve of his 1992 reelection campaign, Yaroslavsky, who came to politics as a leader of the movement to free Soviet Jews, easily disproved the allegations. He went on to help abolish the use of chokeholds, stop undercover surveillance of progressive groups and drive the chief of police from office.

“Compared to the KGB,” Yaroslavsky writes in his new memoir, “ the L.A.P.D. was a walk in the park.”

There are politicians who happen to be Jewish, and there are Jewish politicians. Yaroslavsky, who stood at the center of Los Angeles politics for four decades, was the latter.

‘From Boyle Heights to the Halls of Power’

As almost every page of his new memoir makes clear, Jewish history, issues and values drove him into politics and guided him through his career.

In Yaroslavsky’s book, Zev Los Angeles: From Boyle Heights to the Halls of Power, you surely learn a lot about local politics: the backroom deals that expanded the Santa Monica Mountain Conservancy, how Disney Hall finally got funded and the delicate maneuvers to get a busway through a Jewish neighborhood — Yaroslavsky promised an Orthodox rabbi he’d install a Sabbath timer on a neighborhood crosswalk.

During his long career, first as City Council representative to a largely Jewish district, then as one of five county supervisors, Yaroslavsky was at the center of the crises that shaped the city: the Rodney King riots, the 1994 Northridge earthquake, LAPD corruption and brutality scandals and the ongoing homeless debacle.

But there’s another set of lessons embedded in this memoir, about what it looks like to animate one’s values and honor one’s heritage while engaged in the deeply transactional and often cynical day-to-day of politics.

‘Officers’ training’ for Jewish progressives

Yaroslavsky sources those values from his maternal grandfather, Shimon Soloveitchik, a yeshiva scholar-turned-Zionist firebrand, and his parents, who devoted themselves as leaders and educators in the Labor Zionist movement and created the Folk Shule, a progressive Hebrew school in Boyle Heights. There, Yaroslavsky writes, “We learned that life was not just about grades and textbooks. It was also about social justice, workers rights, civil and human rights.”

At HaBonim summer camp in the Santa Monica Mountains — where his cabin mate was former Forward editor J.J. Goldberg—Yaroslavsky immersed himself in debates on Judaism, current events and social justice.

“HaBonim, for all practical purposes,” he writes, “was an officers training academy for young Jewish activists in the latter half of the twentieth century.”

Fighting the KGB and LAPD

As a student at UCLA, Yaroslavky cut his activist teeth on the movement to free Soviet Jewry; many of his family members were still behind the Iron Curtain. When he organized a 1969 protest at the Los Angeles Coliseum against Soviet athletes, a leader of the local Jewish Federation told Yaroslavsky, “What you’re doing is counterproductive.”

Yaroslavsky and his fellow demonstrators showed up with signs saying, “Let My People Go!” Their vigils and protests swelled to thousands of people.

It was Yaroslavky’s work helping to organize passage of the 1974 Jackson-Vanik Amendment, which tied Soviet-US trade to the freedom of Soviet Jews, that led Yaroslavsky to electoral politics. He launched his campaign for City Council soon after, standing with his remarkable late wife Barbara, a separate but equal force of nature, in front of Canter’s Deli on Fairfax Avenue.

“I was an overweight 26-year-old candidate with two suits to his name who didn’t look like a winner under the most optimistic scenario,” he writes.

Yaroslavsky used the lessons he learned from fighting for Soviet Jews to navigate LA politics. The hardships his family suffered — including his own mother’s death when he was 10 years old — combined with his Jewish education prepared him for battle.

The spoils of that battle are quite a legacy: Yaroslavsky spearheaded measures that ensured more equitable school board representation, checked rampant commercial development and kept oil rigs forever out of Santa Monica Bay. He helped push out a retrograde police chief, instituted a ban on chokeholds and fought for the right of LA janitors to unionize.

He also helped push through projects that reflected the values he held dear: arts venues like Disney Hall, major transit corridors and thousands of acres of parkland in the Santa Monica Mountains.

None of these are obviously Jewish causes. In fact, Yaroslavsky’s book doesn’t mention any typical clichés about his support for Israel or the struggle against antisemitism.

In fact, you could say his accomplishments are those any progressive Democratic politician might have achieved, or at least aspired to. So what makes Yaroslavsky a Jewish politician?

The long arc of his career combines idealism, ethical behavior — in four decades, not a whiff of scandal — and service to the greater good, the community.

Yaroslavsky calls it the “Soloveitchik tradition.” But, really, it’s the Jewish one.

That is to say, Yaroslasvky, who retired in 2014, left the city far better than he found it. God knows there’s still a lot left for a new generation of politicians to do. They have a fine example to follow.