Looking ForwardIf a tree falls in Israel, could it be a harbinger of hope?

Eitan and Amjad, lumberjacks in Jerusalem, often say their morning prayers before starting work — facing opposite directions

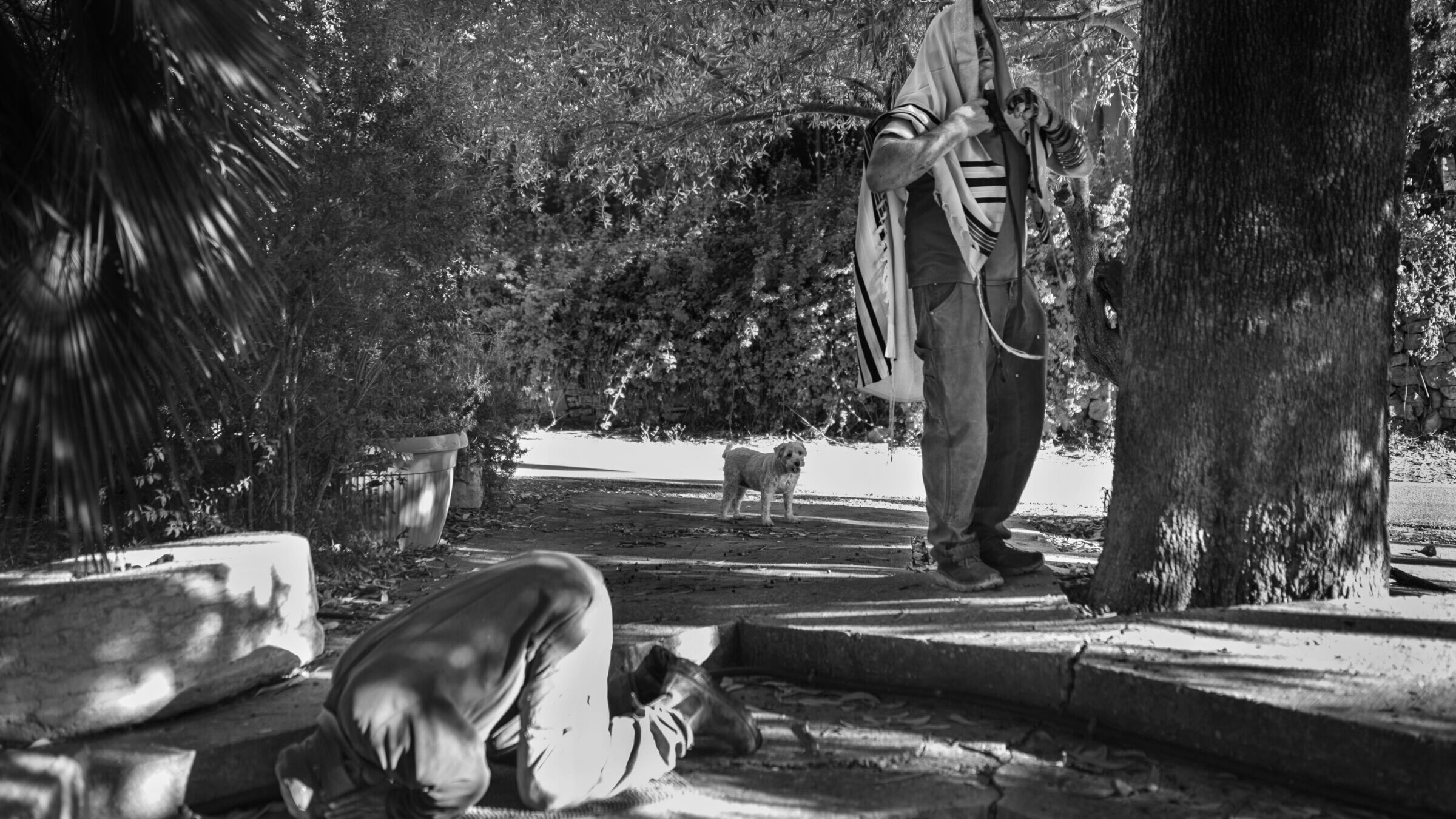

Eitan, at right, faces Jerusalem while his work-mate, Amjad, bows toward Mecca, as they recite morning prayers before starting work cutting down trees in the Jerusalem forest. Photo by Rina Castelnuovo

It might take a moment to absorb what’s going on in this photograph. Maybe your eye, like mine, first goes to the tallit, the Jewish prayer shawl over the head of the man standing by the big tree on the right side of the frame. Maybe that’s because I’m Jewish like that man, an Israeli lumberjack named Eitan.

Perhaps you wonder why he seems to be praying to a tree, and then maybe your eye falls on the man in the foreground, who is also praying — on his knees, head to the ground.

It is morning in Jerusalem, and in the hilly forest beyond it, in beautiful Beit Zayit, Eitan and Amjad, a Palestinian from a village near Hebron, are doing the same thing differently, as people do. They have come at sunrise to cut down a tree — a job with biblical roots that remains one of the world’s most dangerous despite sophisticated tools — but first, they pause to pray.

“They do not pray together. They share one space,” said the photographer, Rina Castelnuovo, who lives in Beit Zayit and scrambled out of bed one recent morning to capture the moment. “Amjad turns to Mecca. Eitan turns to Jerusalem.”

The dog, a Schnauzer-mix from a village near the Lebanese border where disabled children care for dogs as part of their therapy, followed Rina out the door that morning. Her name is Coco.

Harbinger of hope?

It has been another unsettling week in this most challenging year for Israel and for all who care about its future.

Anti-government protests continue to convulse the streets. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu continues to press forward his dangerous plan to undermine the safeguards of democracy. President Isaac Herzog’s visit to Washington only underscored the growing fissures in the alliance of our nations, the increasingly elusive notions of Jewish peoplehood and Middle East peace.

Rina, a veteran photojournalist who I worked side-by-side with during my four years as Jerusalem bureau chief of The New York Times, described the lumberjacks at prayer as “an uplifting scene,” and it is — to a point. Israel advocates often hype partnerships like Eitan and Amjad’s as harbingers of hope for a coexistence that could be.

But Amjad, who is 50, rushed to shield his face from Rina’s camera and only spoke to her on the condition his last name not be published, for fear that his work with Eitan, 56, could be misinterpreted in his West Bank village as collaboration with the Zionist regime.

Eitan’s last name is Wassrzug, and his willingness to share it reflects the inherent imbalance in such relationships due to the Israeli occupation of the West Bank. The situation reminded me of a frustrating experience Rina and I had while trying to tell a different story of Arab-Jewish relationships eight years ago, during the so-called “stabbing intifada” in fall 2015.

It was near the end of my time in Jerusalem, and there was a terrifying eruption of scores of Palestinian attacks on Israeli Jews — lone actors wielding knives — and a fierce crackdown by Israeli security forces.

As we covered the twin narratives surrounding the attacks (and the broader conflict), Rina and I had the idea for a series highlighting pairs like Amjad and Eitan, Jews and Palestinians with human-to-human connections across the deadly divides. We wanted to understand both the backstories of these relationships and how they were being tested by the upsurge in violence and the harsh new security measures hardening the ethnic boundaries within our shared holy city of Jerusalem.

We started with a pair of surgeons at Hadassah Hospital. Israel’s health-care system is a famous showcase for Israeli-Arab collaboration; its workforce is almost 50-50, Jews treat Arabs and Arabs Jews — you may have heard some of this before.

These particular surgeons had been working as a team for years, and had recently treated both the attacker and one of the victims in a stabbing on a public bus. They were compelling characters, fascinating to interview; one detail I remember is that the Arab doctor’s teenage daughter no longer felt comfortable waiting for the bus in a Jewish neighborhood while wearing the uniform of her Palestinian private school. Also: They conversed only in Hebrew — the Jewish doctor never learned Arabic — and the Palestinian had been to the Jew’s home many times, but never the reverse.

The story was never published. It fell apart because the Palestinian surgeon did not feel comfortable with us visiting his home (he lived in the same village as the attacker on the bus) or, ultimately, identifying him by name. Rina and I tried to find other pairs to profile — Jews and Arabs work together in construction, markets and garages, play pickup sports or music together — but kept running into similar obstacles.

Not ‘coexistence,’ just sharing

Rina is an incredible photojournalist, and person. The child of Holocaust survivors, she has been making pictures for 45 years. The week I first arrived in Jerusalem she took me to the most contested area of Hebron and to an Israeli settlement outpost on a remote hill in the occupied West Bank.

We covered hundreds of stories together: She was with me in a tunnel Hamas militants dug underneath the border from Gaza; on a Palestinian stone-thrower’s rooftop when Israeli security forces came to arrest him before dawn; with the mother of a yeshiva student kidnapped and killed while trying to hitchhike home.

She shot stills for The Times for 25 years, then became an award-winning documentarian; her 2017 film Muhi: Generally Temporary chronicles the life of a limbless boy from Gaza who grew up in an Israeli hospital, and she is now working on one about a couple separated in the Holocaust reuniting in their 90s.

Somehow, Rina staves off cynicism, and remains energized, at 67, by every good story. She first met Eitan and Amjad this winter, when they saved a palm tree on her property and two that were falling down on the main road. They returned to do more work at the end of June, the morning after the Muslim festival Eid al Adha, and called Rina before 6 a.m. to ask her to move her car.

After their prayers, she made them coffee, and they talked — about their work together over a decade.

“It’s a job that requires a lot of skill, but first of all a love for trees and great respect for nature,” Eitan told Rina, who emailed me her notes from the conversation. It also requires “a reliable and dedicated ground man,” Rina explained, since “the safety of Eitan hanging between heaven and Earth is in the hands of Amjad, who secures him with a rope.”

The higher the tree, the greater the danger, and all relies on the two men’s communication — in a mix of Hebrew and Arabic, Eitan told Rina. Politics remains “out of the forest,” he said. “For us, it’s not ‘coexistence,’ just sharing.” Amjad nodded.

They told her a story that happened years ago, when Amjad was still in the process of obtaining his permit to work inside Israel’s 1948 borders, and thus working there illegally. A tree branch collapsed, and Eitan found himself hanging from the top. Amjad called the police, and ended up being detained.

“He could have escaped and saved himself, but he saved me,” said Eitan.

Afterward, the Jewish lumberjack helped his Palestinian partner obtain the legal work permit. They said their shared livelihood helps both cope with what Rina described as “destructive politics and continuous security escalation on a land where mothers crying over their children is a matter of routine.”

Eitan told Rina that the people of Jerusalem are “deeply planted — like trees.”

It is a strong metaphor for a city where many residents can trace their family back 10 generations or more, and where many more feel spiritually called to live, or to visit, and to pray. It is true regardless of which direction they might be facing.