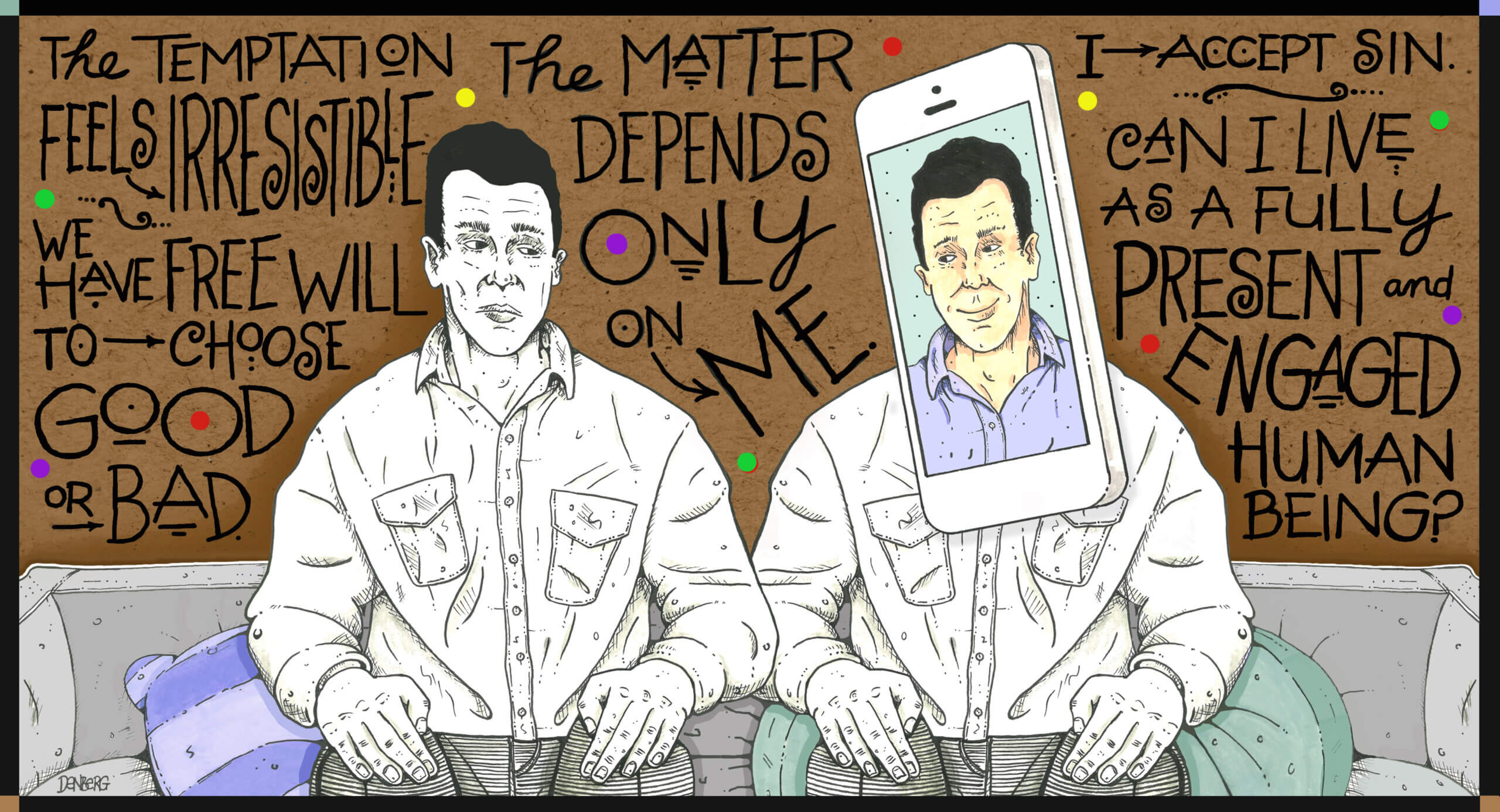

As we approach the High Holidays, I’m making amends for my smartphone addiction

I’m doing teshuva for choosing screens over faces

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The long, drawn-out “um” is the first warning sign.

I recently called a friend who lives in Israel. Having not spoken in several months, I was eager to hear about his upcoming plans for university and update him on my first year of smicha (rabbinic ordination) — an overdue catch-up. But mere minutes into our conversation, I sensed his attention was elsewhere.

“What are you doing now?” I asked.

“Um, uh,” he absent-mindedly began. “What am I doing now…? Oh — nothing much.”

“No,” I pressed, “I mean, which app are you using?”

That broke him from his trance: “Twitter.”

My excitement quickly faded, as I realized he was not listening to a word I said. Over the last few months, I’ve become quite skilled at discerning when friends, family, and even colleagues are dissociated from our conversation — when the allure of TikTok or some pinging notification becomes more interesting than me.

There are few things I find more debilitating than seeking another’s presence and being met with their deadened absence, when I am not enough to hold their attention. It gives me pause before calling again.

And yet, despite my grievances, I am an equally liable offender.

WhatsApp messages, new emails, and Twitter notifications constantly entice me from the work meetings or casual phone calls deserving my presence. As a rabbinical student, I learn about the importance of active listening and attentiveness required in successful personal relationships, about the need to be there for others. And though I know the hefty price of turning away, I always seem to pay it. The temptation feels irresistible.

My instinct is to fault my smartphone; its ease, accessibility and that gripping, blue light are the ones to blame. I can justify it, too: Smartphones (and their social media pals) have decimated teens’ and adults’ mental health, and their use is strongly correlated to worsened mental health in adulthood. The Atlantic asked recently, “Are Smartphones Destroying a Generation?” The data clearly answers: Yes, they are.

But deflecting the blame solely to my phone feels misguided. A core tenet of Judaism is humankind’s free will, our divinely endowed agency to choose good or bad, as Maimonides lays out. The 20th-century Rabbi Meir Simcha of Dvinsk identifies free will as our creation b’tzelem Elokim, in God’s image. To deny my choice is to deny my humanity. It’s my fault, not my smartphone’s. That’s why, as the Hebrew month of Elul rolls around, I’m reckoning with my choice of screens over faces.

Bridging summer and fall, Elul is the “season of teshuva,” a priming for the High Holidays centered on judgment and atonement. Teshuva — literally “returning” — is the process of aligning our practical lived self with our theoretical ideal self; it is a form of aspiration or, as Agnes Callard writes, “the distinctive form of agency directed at the acquisition of values.”

As it relates to my smartphone and my relationships, teshuva is my decision to be the type of person who does not open their phone when others expect their attention; the type of person who listens when others speak.

In his book Stages of Faith, James Fowler, an American professor and theologian, writes from his research about the different maturity levels people reach in their religious journeys. At the sixth and highest level of his model, Fowler describes those living in the “kingdom of God,” who exude “a special grace that makes them seem more lucid, more simple, and yet somehow more fully human than the rest of us.” I found his description striking when I first read it, and every time after yields the same humbling effect. I yearn to be, as he says, “more fully human.” Choosing screens over faces prevents that.

I think that touches at the heart of my struggle with my smartphone — a struggle I think we all seem to be facing: living with humanity while living with technology. The escapes and distractions technology provides are endless; I can go hours — days, even — stimulating myself while numbing my emotions and interactions with my phone’s endless supply of entertainment: new articles, Twitter or literally any app I have downloaded. It may also explain our epidemic of loneliness and isolation.

David Foster Wallace wrote poignantly of this crisis 30 years ago: “Lonely people tend rather to be lonely because they decline to bear the emotional costs associated with being around other humans. They are allergic to people. People affect them too strongly.”

I might adjust Wallace’s words to say that we are allergic to the brunt of humanity. Raw, human life affects us too strongly. Friends speak slowly; apps move quickly. Friends can bore; social media can entertain. Human beings are not curated to wholly engage us — they require active participation, despite our fidgeting impulse that resists such effort.

My teshuva with my smartphone concerns much more than simple bad habits; it concerns my very ability to live as a fully present and engaged human being.

The Talmud tells the story of Rabbi Elazar ben Durdaya, who faces a religious reckoning that propels him to seek out teshuva. After pleading with the mountains and hilltops, the sun and moon to pray for divine mercy, Rabbi Elazar faces a striking realization: “He said, ‘The matter depends only upon me.’ He placed his head between his knees and burst into tears until his soul left his body.” He alone bears responsibility. The story ends with a divine voice proclaiming his entry into the World to Come.

I wish I could say that my phone is always silenced and tucked away during work calls; that I never supply absent-minded “yeahs” during FaceTimes with my sister; that I never turn away from someone turning toward me. But my teshuva is still a work in progress.

What I can say is that I accept the “sin” of social disconnection as my own, not my smartphone’s. I perpetuate the problem, so only I can muster a solution. The matter depends only upon me — and I’m not willing to let my smartphone take that from me, too.

To contact the author, email [email protected].