‘If I were injured there, the best thing would be to die’: An ICU doctor’s devastating mission to Gaza

Women and children make up the majority of the victims of Israel’s assault on Gaza

A young boy undergoes a medical examination by a doctor at the overcrowded Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City following an Israeli airstrike, Oct. 18, 2023. Photo by Mohammed Zaanoun/Middle East Images/AFP via Getty Images

Burned children were the hardest.

I tried to get the 7-year-old Palestinian girl in front of me, with burns covering 40% of her body, to eat some beans that I had brought from New York to Gaza. Burn patients need extreme care, including a high-protein diet. Her mother was also burned, and her father and brother had been killed in the airstrike that destroyed their home and injured her so severely.

The only pain relief I had to offer her was Tylenol. The little girl was in excruciating pain and refused the beans. All she wanted, she cried, was an egg and french fries, both of which were impossible to find in Rafah these days. I thought of the line of stalled aid trucks I had passed traveling into Gaza from Egypt, one of which was stacked full of eggs.

I am an intensive care doctor practicing in New York City, with more than 20 years of experience working with trauma patients in the United States. In January I joined MedGlobal, an American NGO, on a 10-day humanitarian mission to Gaza. The civilian impact of the war that I witnessed in Gaza was almost beyond comprehension.

Arriving in a war zone

Our volunteer team included an orthopedic surgeon, a plastic surgeon, an anesthesiologist and two nurses. I flew into Cairo to meet up with the mission, where we joined a U.N. envoy to enter Gaza from Egypt. It took us 14 hours to cross into the strip. At the Rafah border crossing we passed hundreds of trucks with supplies, food and medical equipment unable to enter Gaza.

As part of our medical capacity-building efforts, we brought medical supplies to replenish vastly under-resourced hospitals and clinics in Gaza. We were forbidden, however, to bring any intravenous pain medication such as morphine, as that would get confiscated. This proved to be very challenging, as patients who are unresponsive or on a ventilator cannot take oral medication.

What we saw upon entering Gaza was beyond belief. Thousands and thousands of people made homeless through the violence were living in tents. We were consumed by the reality of more than 1 million displaced people living in close proximity without adequate sanitation or clean drinking water.

MedGlobal has had a permanent base in Rafah since before the war. We stayed in a house where the local staff that runs the MedGlobal clinic lived, where we slept on the floor. It was so cold that I would wear three layers of clothes at night and double up my blanket to sleep, and I was still freezing. We could hear the blast of bombs and see the smoke rising from where we stayed. At night, the constant hum of Israeli drones made it impossible to sleep.

The first day, we worked at Najjar Hospital in Rafah, where I was in the emergency department. I’ve seen a lot of things as an intensive care doctor, but nothing like this. It was complete chaos.

Najjar is normally a primary care hospital, and was not set up to handle acute care. Over a hundred people were lying on the floor begging for help and trying to grab at you. The volume of patients was overwhelming. I saw several people die just in my first few hours there.

What it’s like to be a patient in Gaza

These days, if you are a patient and arrive conscious to a hospital in Gaza, you will not be seen. There are too many who are unresponsive or “coding,” experiencing cardiac arrest. If you are elderly, you will also be ignored, as there are too many young people in need of emergency care. Palestinians who come to the hospital suffering not from mass casualty events but from chronic illnesses like kidney or heart disease, people with special needs, die slowly at home, in tents and on the floors of the hospital.

The next day we went to the European Gaza Hospital in Rafah, where we stayed for the rest of our mission. Displaced people had made the hospital hallways their home. There was barely any room to walk through the corridors. The desperation and pain on the patients’ faces were heartbreaking.

There, I worked in the intensive care unit, and every day I would see patients with burns, gunshot wounds or blast injuries. Many of them required amputations, which our orthopedic surgeon was responsible for. There was no pain medication we could provide for the amputations, so our anesthesiologist would give the patients nerve blocks. The blocks last only temporarily though, and the pain afterwards continues for weeks.

The days were filled with one horror after another. I saw a pregnant woman whose uterus was torn open in a blast. About 60% percent of the patients were women and children. Missile wounds to their heads, chests or abdomen had left them totally unconscious with very little hope of meaningful recovery. I’ve dedicated my life to helping people, and it’s very painful as a doctor to admit the following: If I were living in Gaza and I got injured, the best thing would be to die.

On the last day of my mission, a young man and then four children, mostly younger than 10 years old, were rushed to the emergency room. The children were all suffering from gunshot wounds to their heads. One of their fathers told me that Israeli tanks had withdrawn, and so they had attempted to return to their homes in Khan Younis, but Israeli snipers had, apparently, not withdrawn.

I was stunned. How could anyone shoot a child? How could innocent children be perceived as a threat? The father of a little girl begged me to save her, but they all had traumatic brain injuries and were unlikely to survive.

The young man had a severe gunshot wound in his leg. His artery had no palpable pulse and he would for sure lose his leg if he was not operated on within minutes. Yet there was no operating room space, no available surgeon and no bed for him. He was moved to the floor in the emergency room where he lay, helpless.

The helpers

We are witnessing a humanitarian nightmare in Gaza. The health care infrastructure is collapsed and almost nonfunctional; there simply are not enough medical staff, supplies, medicines or fuel to render it operational. On our mission, we brought 36 suitcases full of supplies, but it is nowhere near enough.

The staff at all of the hospitals work relentlessly, but the look of despair on their faces will never leave my mind. Almost all had lost family members and their homes, and are living at the hospitals. They’ve seen so much death.

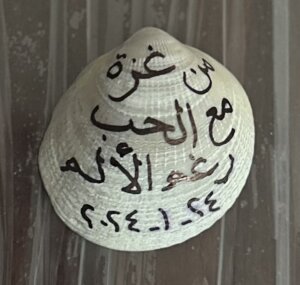

Despite all of this suffering, Palestinians are the nicest people that I’ve worked with. They’re still smiling, still persevering each day. One day, a little kid insisted on giving me his cookie, saying, “Thank you that you’re here.” A doctor gave me a bracelet, telling me that it was all she had. “I can’t help you,” I said. “But you bring us hope,” she replied.

I could not stop thinking about the burned girl I had treated. I knew the only way she could survive was if she received skin grafts, which meant she needed to be transferred out of Gaza to a burn unit. Very few patients are permitted to be transferred out of Gaza, however, with typically only one person every other day being allowed to leave. Her case was presented to the World Health Organization and Red Cross, both of whom advocated for her transfer.

I stayed in touch with doctors in Gaza and learned after I returned home that she had ultimately been transferred to Cairo, but it was too late. She died a day after arriving in Egypt.

This suffering in Gaza has to stop. The civilian impact of Israel’s war against Hamas is unfathomable. I still wake up a couple of times a night, struggling to sleep after what I saw in Rafah. I promised my colleagues in Gaza that I would return, but I hope that this war ends long before I do.