I’m obsessed with Caitlin Clark. Do I choose her over Shabbat?

A crucial game for the Iowa basketball star in her final collegiate season tips off right at candle lighting

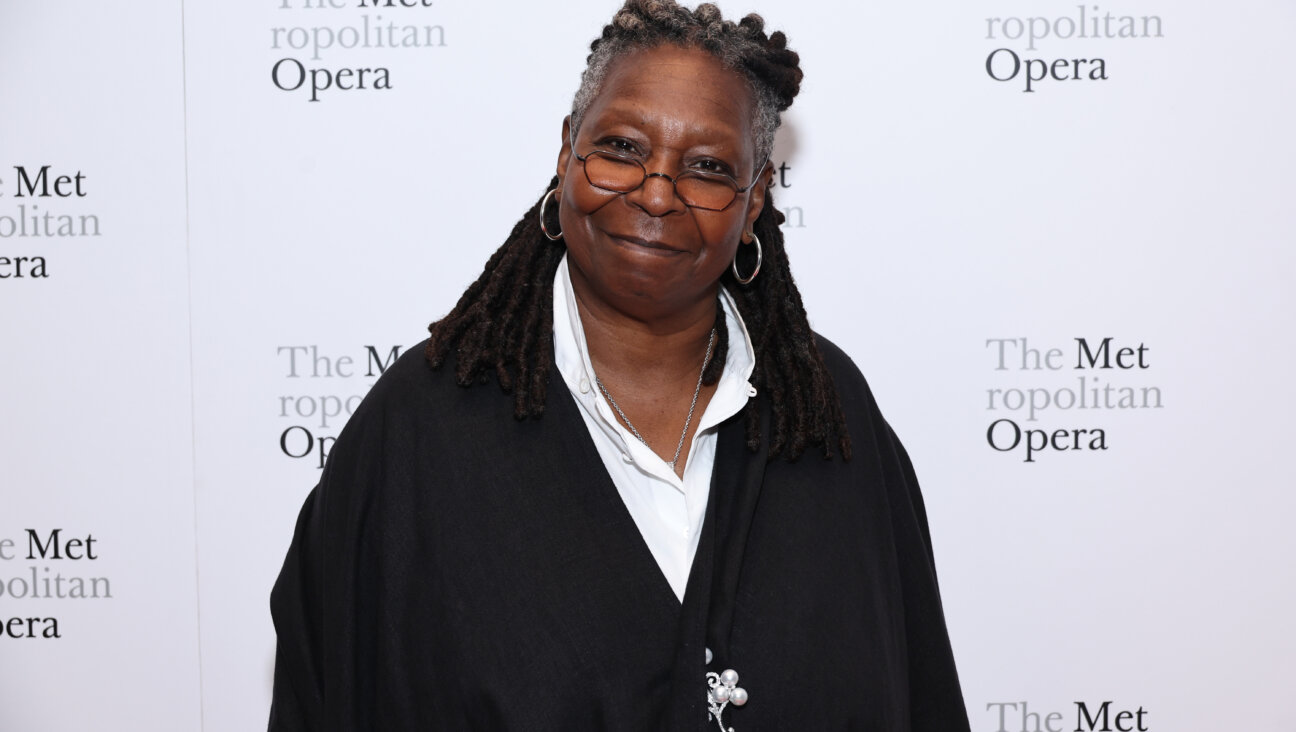

Caitlin Clark of the Iowa Hawkeyes celebrates after beating the LSU Tigers 94-87 in the Elite 8 round of the NCAA Women’s Basketball Tournament, April 01, 2024 in Albany, New York. Photo by Andy Lyons/Getty Images

I am in love with Caitlin Clark, the point guard for the University of Iowa Hawkeyes, and now the all-time leading scorer for men and women’s Division I basketball.

I also observe Shabbat.

And Clark’s next game in the NCAA Championships — a decisive one, in her final, remarkable season as a college athlete — is a Final Four match-up vs. the University of Connecticut, which happens to be taking place on Friday night, with tipoff happening right before we light Shabbat candles here in Brooklyn.

Shabbat and basketball both help me express parts of myself that feel raw and vulnerable: in basketball, competition; on Shabbat, a holy presence. To be unable to watch Clark play this Shabbat at a moment when she has led the transformation of NCAA women’s basketball into must-see television, feels like a wrenching choice between two versions of myself who are fundamental to my identity.

For the sake of transparency, my love for Clark is new. Despite being an avid basketball player in my youth, I only occasionally tune in to a college basketball game these days. I’m the kind of sports fan who will ignore March Madness until the bitter end, when I finally catch one game and pour all of the ferocity that normal sports fans express over an entire season into four, very intense quarters.

I first saw Clark play a full game on Monday night, in an Elite Eight matchup against Louisiana State University. Her three-pointers were what sealed the deal for me. I’m mildly embarrassed that I wasn’t transfixed by one of her more subtle skill sets, like her mental toughness, or unerring ability to find an open teammate. But the intoxication of watching her sink nine three-pointers in the game, often from five or seven feet behind the three-point line, awoke a deep, competitive glee in me that I hadn’t accessed since playing AAU basketball as a teenager.

I grew up as an insecure only child; I struggled to stand up for myself, and the basketball court became the one place where I could not only be aggressive, but where my aggression was valued. I relished becoming a fierce defensive player. My great joy was ruining the game of the opposing team’s best player, physically haranguing her until her frustration would boil over.

At school, my body was tall, gangly and often mocked.

On the court, I loved using it to push, block and box out.

In life, I was walked over.

In basketball, I was the first girl in elementary school to be ejected from a game with a technical foul.

Ordinarily, deciding to watch perhaps the greatest women’s collegiate player ever would be a no-brainer: She reminds me of such a profound part of my own upbringing, reigniting a part of myself I haven’t accessed since I was a kid. But my Shabbos observance is already imperfect. And when it comes to choosing between two implacable priorities, Jewish thought tends to offer up even more choices, rather than answers. In the words of a rabbi friend of mine: “What if we ask the question a different way?”

My Shabbat observance, while not as new as my Clark fandom, is still a relatively recent practice. I was not raised in an observant Jewish household. But during the pandemic, when my husband and I had both been laid off from our restaurant jobs and were living in my in-law’s finished basement, the days blended together, becoming a horrifying abyss of time to fill.

I began observing Shabbat out of desperation: I needed a practice to add definition and holiness to my weeks and days. I had no idea what to do with my life, or how long we would be inside hiding from a deadly virus. But I knew that each Shabbat I would braid challah, light candles, and put away my phone and all of the horrible news that came with it. Shabbat sanctified time for me, at a moment when time was filled with terrifying questions I couldn’t answer.

Still, I was far more rigid and diligent about my basketball practice as a child than I have ever been about my Sabbath practice as an adult. I never use my phone or computer and do not do any work on Shabbat; I try to avoid television screens and stick to reading. But when my husband, who does not keep Shabbat, turns the television on, I have been known to watch. I do my best to not use money on Shabbat, and do all of my cooking preparation in advance. But if I am desperately craving a bagel for Shabbos breakfast, I will go and buy a half dozen.

In contrast, when it came to basketball I was single-minded: I was so insistent about my conditioning that the local health club devised a fitness test for me to pass in order to allow me to use the free weight room without supervision at the age of 12. I spent all of my free time at the gym, trying to take 1,000 shots a day like my hero Diana Taurasi did.

Having been 5’7” since I was 11 years old, I was often relegated to playing tall-girl positions like center and power forward, which meant that I had less practice handling the ball and taking three-point shots. Resolute that I would not get stuck under the basket rebounding, I practiced dribbling as fast as I could down the court with my head up. I quit piano and all other extracurriculars, determined that I would, one day, play Division I basketball, or maybe even for the U.S. Olympic team.

And yet. I know in my gut that skipping Shabbat for March Madness, even given my love for Clark, doesn’t feel right. It is not the kind of casual television my husband would put on that I could furtively watch over my book, but a special event. It certainly does not rise to the level of pikuach nefesh, a principle that articulates that violating Shabbat to save a life is a commandment. (Another Shabbat-observant Jew, Forward staff reporter Louis Keene, told me that as a kid, he and his friends would walk past a dry cleaners with big screen TV’s that stayed open on Shabbat in order to watch NFL wildcard games.)

It’s about past versus future: No matter how much I love Clark, the hyper-fixated young basketball star belongs to who I once was, and Shabbat belongs to who I am becoming — always, in the end, more essential. I aspire to come to keep Shabbat more completely one day, and am already nervous that sharing my imperfect observance will lead to a flood of judgy emails. But deep down, I’m confident in my love for Hashem, and that faith is not a perfect path but an act of wrestling, like our patriarch Jacob did with the angel.

In the end, thanks to technology, I will figure out a way to record the game and watch it after havdalah. (Louis warned me that I’ll have to extend my Sabbath by another couple of hours if I don’t want to have the game results spoiled by the Internet.) But a 27-hour Shabbat feels like a worthy sacrifice to be able to support both versions of me — the basketball player, and Shabbat-observant Jew — at the same time.