We can feel brokenhearted for the suffering of the children of Isaac and of Ishmael. We must.

A rabbi rejects how expressions of compassion are regarded with suspicion in today’s conversations about Israel

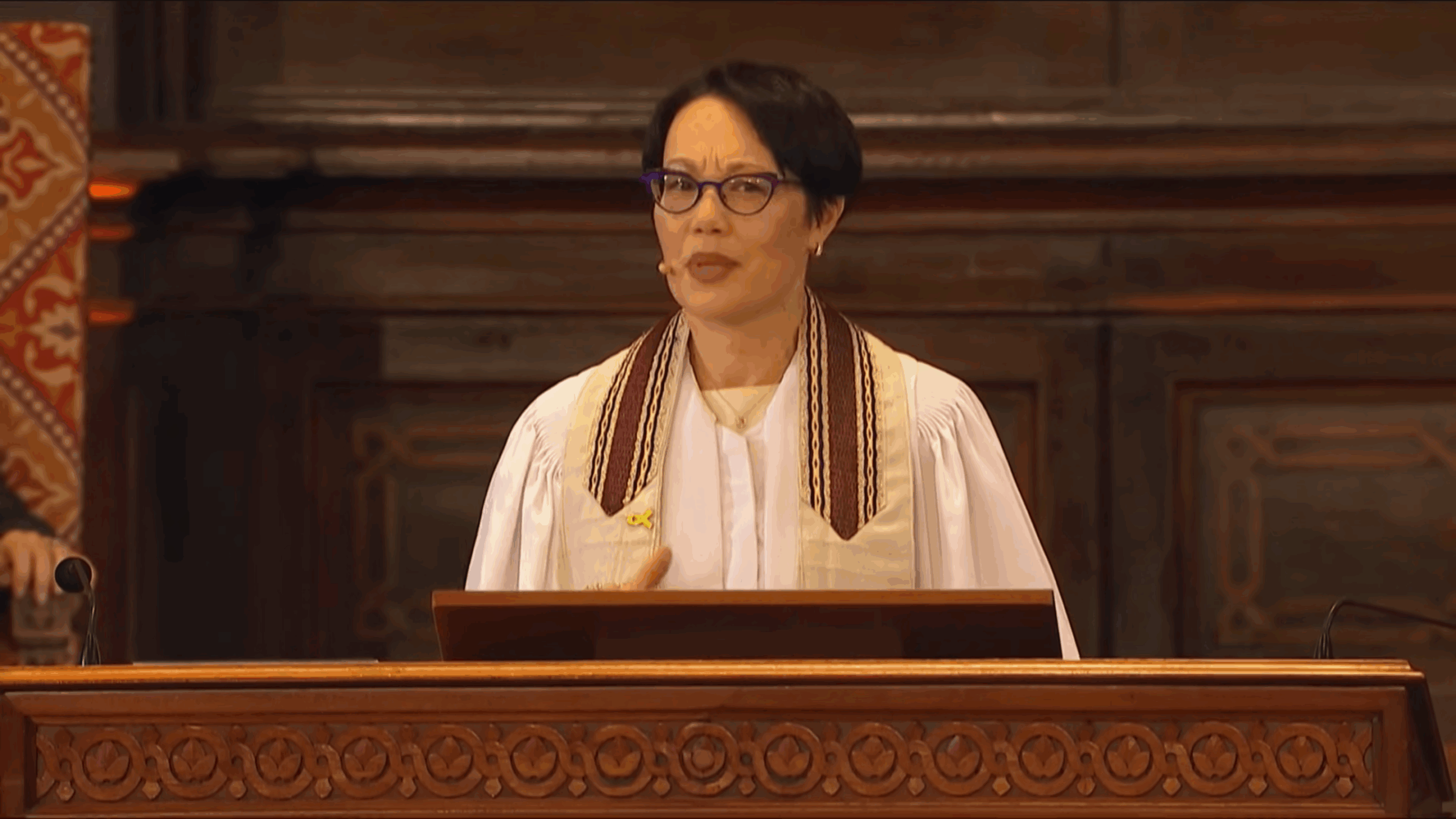

Rabbi Angela Buchdahl speaks during her sermon on the first day of Rosh Hashanah, Sept. 23, 2025. Screenshot of Central Synagogue livestream

(JTA) — This piece was originally delivered as a sermon titled “The Cries of Isaac and Ishmael” at Central Synagogue on the first day of Rosh Hashanah in 2025.

I have been a rabbi for 25 years, 20 of them at Central Synagogue, and I have never been so afraid to talk about Israel.

I want to tell you about my unconditional love for the Israeli people and our beleaguered homeland, still desperately struggling to bring its hostages home, still trying to eliminate Hamas — terrorists that not only refuse to lay down their arms but intentionally trap their own people inside a combat zone.

But if I tell you these things, all of which I believe, some of you will just stop listening. And decide that I’m no longer your rabbi.

I also want to tell you how my heart breaks over the civilian deaths, and tragic suffering in Gaza, the shattering destruction of Palestinian homes and cities. I want to denounce settler violence in the West Bank. And the rhetoric from far right government ministers who talk about annexation of the West Bank and expulsion of Gazans instead of ending this war and bringing our hostages home.

But if I tell you these things, all of which I also believe, some of you will just stop listening. And decide that I’m no longer your rabbi.

It’s scary to talk about this. Not because I’m afraid of losing my job. But because I’m afraid of losing you.

This Israel conversation is ripping our community apart. Not just here at Central, but across the Jewish world. Among friends. Within families.

It’s been the most painful experience of my rabbinic career. It’s keeping me up at night, watching the world, and many in our community, lose all empathy for the State of Israel. And at the same time, watching so many of us lose all empathy for the Palestinian people.

It now seems that any expression of compassion for “the other side” is regarded with suspicion – as disloyal, or even threatening. Is our capacity for empathy so finite? Are our hearts so small, that if we increase our empathy for certain people, That we need to reduce it for others — until one day, we conclude: that ‘other side’ is not deserving of any compassion? Any regard?

This zero-sum, empathy calculus has encouraged us to dismiss and demonize each other. And not just in Israel’s war, but in ideological battles being fought in our nation every day. I’m terrified today – not only by the chilling rise in antisemitism, by frequent mass shootings, and the contagion of political violence, but also by people’s responses. Over and over I see a shocking lack of decency or compassion, even for murder victims. People feel emboldened to say: ‘They deserved it.’ It’s a cottage industry of schadenfreude, vengeance and even glee.

Not only do people act as though empathy is finite, some people want us to believe that empathy is actually dangerous.

Once upon a time, empathy seemed as unobjectionable and wholesome as motherhood and apple pie. Who could be against it? But in the last few years, an unlikely coalition of politicians, professors, even pastors have used it as a political weapon, calling it “toxic,” and waging a “war on empathy.”

A Christian theologian published a book this year entitled “The Sin of Empathy.” Empathy, he argues, demands we inhabit the feelings of another person, which doesn’t help the sufferer. He offers a simple analogy: if someone is drowning in the river, empathy asks us to jump in alongside them, putting us both at risk. Whereas sympathy says, I’ll keep my distance, stay on firm ground and throw you a life preserver.

His analogy may sound reasonable on the surface, but in practice it has been wielded by many to dismiss the cries of victims, and to excuse indifference and cruelty. It’s also used to justify some strange policies. For example, the pastor claims that women’s natural tendency to excessive empathy is why they shouldn’t be permitted to be ordained. I confess, despite being a woman, I don’t have much empathy for that argument.

But there are powerful people speaking out against empathy. This past winter, while leading an effort to eliminate much of our nation’s foreign aid, Elon Musk declared that empathy is “the fundamental weakness of Western civilization,” And that empathy was enabling “civilizational suicide.”

Judaism says otherwise. Our tradition reveals that the real danger we face is not that we might have too much empathy. It’s that we might not have enough. Our compassion – like God’s – should have no limit. And we must extend it beyond “our side,” to encompass care for the other.

The challenge of empathy is starkly illustrated in the Torah narrative we are instructed to read on the first day of Rosh Hashanah: the story of Hagar and Ishmael.

God promised our first ancestors Abraham and Sarah that they would multiply and be a great nation, but after many years together, they have no offspring. So Sarah offers Abraham her Egyptian handmaiden, Hagar, to create an heir.

When Hagar becomes pregnant, she acts disrespectfully toward Sarah, and the relationship between the women becomes so strained that Hagar flees. But with God’s encouragement, Hagar returns and gives birth to Ishmael, Abraham’s first son. Years later, Sarah finally gives birth to Isaac. And begins to worry that Ishmael is a threat to Isaac and his inheritance, so she demands that Abraham cast out Hagar and Ishmael.

Abraham reluctantly agrees, and banishes them to the scorching desert where Hagar, who cannot bear to watch her son starve, weeps from a distance. A child is expelled from his home, left to die of hunger and thirst, while our ancestors seem to exhibit shocking indifference.

We know Sarah bears some culpability for this terrible situation. And Abraham too. We can even fault Hagar for her early scorn for Sarah. But one thing is clear: it isn’t Ishmael’s fault. How could Abraham and Sarah not feel empathy for this starving child? We know God does. God hears Ishmael’s cry, opens Hagar’s eyes to a well of water, and promises her that Ishmael will become the father of a great nation, which the Abrahamic faiths recognize as the Arab people.

This story might feel a little too close to home right now.

And let me assure you: This Torah portion wasn’t selected by some overly empathetic female rabbi. Our ancestors selected it centuries ago – to read on Rosh Hashanah – also known as Yom HaDin, the Day of Judgment. We read this story as our tradition asks us to take a cheshbon hanefesh, an accounting of our souls.

How do you hear its message this year? How many of us, our hearts so aligned with our Israeli brothers and sisters, so finely attuned to the dangers they face, have become callous to a generation of Ishmael’s children cast from their homes, wandering in a wilderness, many of them without enough to eat or drink?

It’s clear to me that Hamas is fundamentally culpable for today’s devastating situation – for starting this war on Oct. 7, for embedding themselves in civilian populations and under hospitals and schools, for executing hostages and refusing to return the remaining ones, for stealing humanitarian aid to fund their war.

I also pray that the Israeli government is doing an accounting. So much criticism of Israel has been biased, even blatantly dishonest. But Israel made no secret of its food blockade from March to May – justifying its decision based on the abundance of aid delivered during the ceasefire. The blockade was an unsuccessful and unwise attempt to force Hamas to surrender. And Israel is responsible for its consequences.

Some of you only fault Israel for this situation, and some of you only blame Hamas. But one thing is clear — it isn’t the children of Gaza’s fault. They did not start this war; they aren’t responsible for antisemitism at the United Nations; or unreliable numbers from the Gazan Health Ministry; they didn’t choose which photograph would be printed on the cover of the New York Times. Whether the hungry children of Gaza number in the hundreds, or the hundreds of thousands, matters far less than the simple fact that there are children who are suffering, exiled, and desperate. We cannot look away.

And yet, when UJA-Federation of NY recently made a $1 million donation to IsraAid, a trusted Israeli humanitarian organization, working with the support of the Israeli government in Gaza many in our extended community publicly denounced this effort to feed hungry Palestinians — even though UJA has given over $300 million to support Israel since this war began. Some even went so far as to pledge that for this “sin of empathy,” we should never give another dollar to UJA.

What happens when we stop caring? And I don’t mean what happens to society or to the world — I mean what happens to our souls? It is not only some of Israel’s defenders who need to find more empathy. Many of Israel’s critics also need to search their souls on this Rosh Hashanah. Within our community, there are those of us whose understandable grief for civilian suffering in Gaza has led us to take the worst accusations against Israel at face value, and for some, to abandon the entire project of a Jewish state.

Too many of us cannot muster any empathy for Israeli families who have lived for two years under direct attack from Hamas, Hezbollah, the Houthis, and Iran — literally from every direction, who have faced security threats since the very founding of the state. Too many of us cannot spare any regard for the Israeli reservists, who have been away from their families for hundreds of days to defend the only Jewish state we have.

Too many of us ignore that 80% of Israelis themselves want to see the hostages home and the war ended. They have been in the streets, weekly, to protest the actions of their own government. Instead, too many of us label all Israelis “occupiers,” and support boycotting Israeli academics, filmmakers, artists, musicians and scientists. There are members of our own congregation who are disturbed by our weekly prayer for Israel. Or who object to the Israeli flag on our bimah, even though the empty chair it covers stands for the 48 remaining hostages whose families still await their return.

We all need to understand that feeling empathy for the other is not a betrayal of our own side. It is not disloyalty. We can feel brokenhearted for the suffering of the children of Isaac and Ishmael.

Indeed we must. The biblical scholar Tikva Frymer-Kensky writes: “The story of Sarah and Hagar is not a story of the conflict between ‘us’ and ‘other,’ but between ‘us’ and ‘another us.’”

We are all the children of Abraham. Hagar’s name has the same spelling as ha-ger, “the stranger.” She is the ultimate “other,” an Egyptian, a slave. But only a few generations later — it is the Israelites who are slaves in Egypt. We are the stranger. We are the other.

Our Torah insists we never forget this. Our origin story as a people reminds us: “Do not oppress the stranger, for you know the heart of a stranger — you were strangers in the land of Egypt.” We recreate that memory every Passover. And when we feel glee at the death of our enemies in the Red Sea, God rebukes us: My children are drowning and you are celebrating?!

And on this holiday, Rosh Hashanah, we are instructed to read the story of Hagar and Ishmael, so that we can begin our new year with an honest accounting of how we have treated the stranger, the other, the child.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, of blessed memory, the former Orthodox chief rabbi of England, warned that: “Fear of the one-not-like-us is capable of disabling the empathy response. That is why this specific command [to love the stranger] is so life-changing… It even hints that this was part of the purpose of the Israelites’ exile in Egypt in the first place.”

This war has tested our empathy. All of us. I see the ways that my fear has disabled my empathy response. I still struggle to find the emotional bandwidth to read the tragic stories coming out of Gaza while my extended family is still held captive, while calls to “blacklist Zionists” or to “globalize the intifada” still ring around the world, and even this city.

But who do we become when we harden our hearts?

Rachel Goldberg-Polin, whose son, Hersh, was taken captive on Oct 7 and held in tunnels for nearly a year before he was executed by Hamas, she more than anyone, would be justified in losing herself to rage. But instead, she had the courage to say: “I can feel bad for the innocent in Gaza, because my moral compass still works. You don’t need to choose.”

This Rosh Hashanah, we are invited to create the moral universe we want to inhabit. One where empathy is not finite but expansive. Where we see the suffering of the other and we do not harden our hearts. The opponents of empathy call it a weakness. Our Torah sees it as our superpower. Judaism teaches us that this feeling of otherness that we are feeling right now, there is a purpose to that exile — it is how we forge the heart of a stranger.

A “heart of many rooms,” our tradition calls it.

A heart that is big enough to care for our own, and the other. A heart that is strong enough to respond to the cries of both Isaac and Ishmael. A heart with empathy enough for ALL of God’s children.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of JTA or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.