Does that Trump Time magazine cover really reference a Nazi war criminal?

Careful observers have noticed an eerie resemblance between Trump’s pose and that of Alfried Krupp

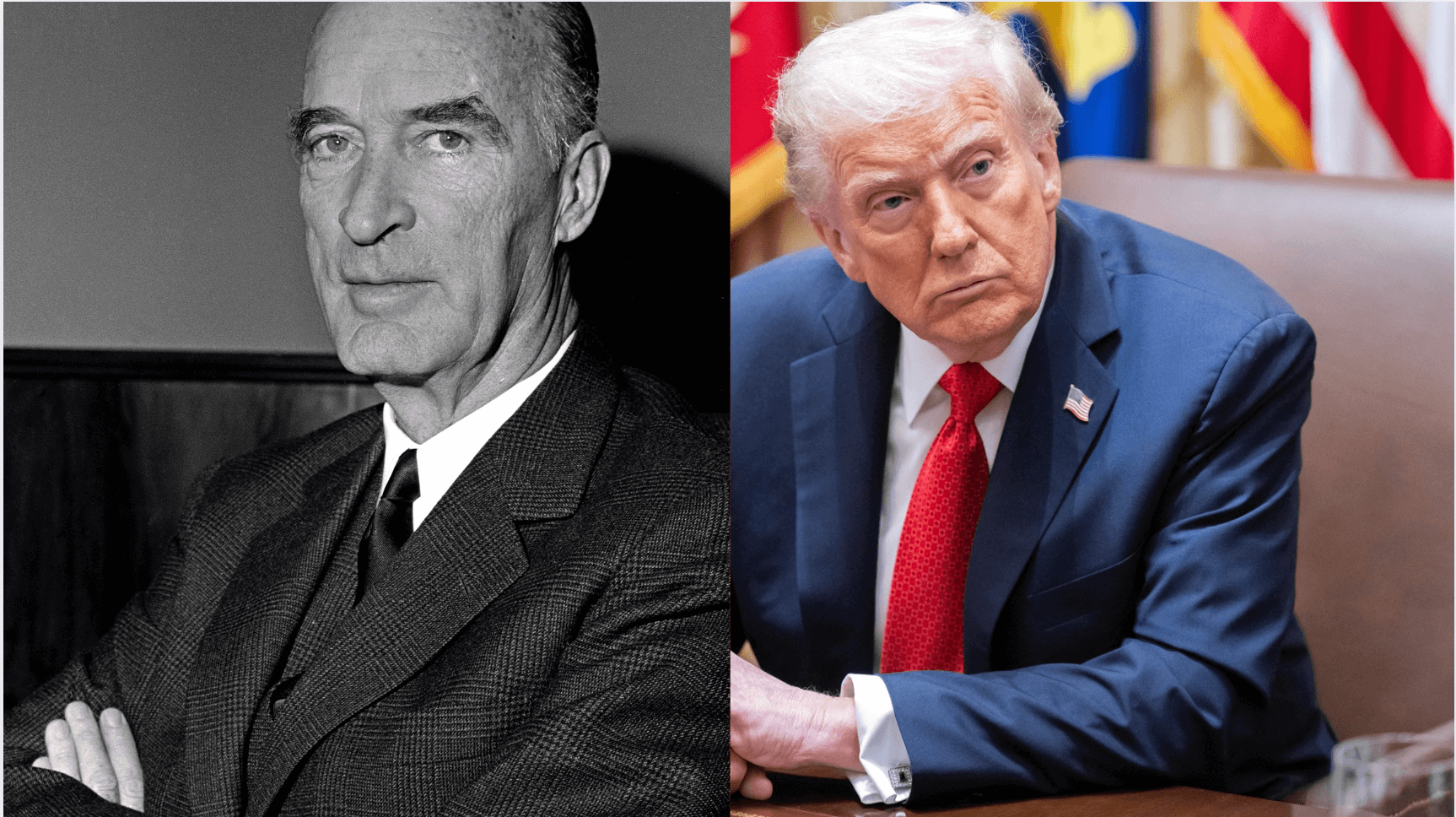

At left, Alfried Krupp. At right, Donald Trump in the Oval Office. Photo by Getty Images

As Adolf Hitler’s armies rampaged across Europe and the Soviet Union, they were followed by German industrialists who plundered the occupied countries —seizing raw materials, dismantling factories and exploiting civilians as forced laborers. Private enterprise became embedded in the machinery of conquest and genocide.

Among them, few wielded more power than Alfried Krupp, owner and CEO of the vast industrial empire that bore his family’s name.

During the war, Krupp’s factories produced tanks, artillery, ships and munitions, operating more than 80 plants across Nazi-occupied Europe. About 100,000 forced laborers toiled in his mines and factories, including Jewish inmates from Auschwitz. Conditions were inhumane, especially for Jews and Soviet POWs, who endured beatings, starvation and exposure. The death toll remains uncertain, but it likely numbered in the many thousands.

Krupp was convicted of war crimes at Nuremberg in 1948 and sentenced to 12 years in prison. He served just 30 months.

After West Germany’s founding in 1949, the occupying powers came under intense pressure — from federal, state, and local officials, civilians, former Wehrmacht soldiers, and even religious leaders — to grant amnesties to war criminals. Many West Germans wanted to bury the past. As part of a deal to secure West Germany’s partnership in the emerging Cold War confrontation with the Soviet bloc, the U.S. and its allies acquiesced, freeing thousands of convicted war criminals. Among them was Krupp, who walked out of Landsberg Prison on Feb. 3, 1951.

Most Americans today have never heard of Alfried Krupp or his war crimes. And few could have guessed that his name would resurface because of a photograph of Donald Trump on the cover of Time magazine.

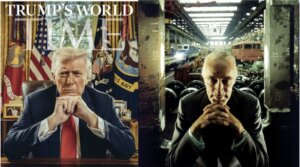

Almost as soon as the Time cover appeared on social media, people began noticing that Trump’s pose was eerily similar to Krupp’s in a 1963 Newsweek photo. The resemblance went viral. Time denied any connection, but the visual echo struck a nerve — especially given Trump’s authoritarian turn in his second term.

So who was Alfried Krupp?

As often happens with Germans born into old dynasties, his full name is a mouthful: Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach.

The Krupp family’s involvement in arms production dates back to the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), when Anton Krupp oversaw a gunsmithing operation in Essen. Over the centuries, the family pioneered high-cast steel, revolutionized artillery, and gave Germany a decisive edge in conflicts like the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), cementing Krupp’s role as the empire’s premier arms supplier.

Alfried was the son of Bertha Krupp, heiress to the industrial empire, and Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach, a diplomat and industrialist. The Krupp firm supplied weapons and materials to Imperial Germany during World War I. Alfried joined the Nazi Party in 1938, though the company had aligned itself with the regime’s militarization years earlier. He assumed his father’s duties after the war began and collaborated closely with the SS, personally negotiating contracts for the use of concentration camp labor — including Jewish inmates from Auschwitz.

Krupp and 11 other executives were tried before a U.S. military tribunal in Nuremberg from December 1947 to July 1948, charged with crimes against humanity, war crimes and plunder. Krupp denied personal guilt and claimed his role was apolitical.

“We Krupps never cared much about [political] ideas. We only wanted a system that worked well and allowed us to work unhindered. Politics is not our business,” he said in 1947.

Prosecutors argued that Krupp’s firm was not merely complicit but actively expanded its empire through Nazi aggression. They documented the systematic looting of industrial assets from France, Belgium and the Netherlands, contracts with the SS for concentration camp labor, and the use of punishment cages for workers.

Convicted of war crimes for plundering occupied nations, Krupp was sentenced to 12 years in prison and ordered to forfeit all property and industrial holdings. One defendant was acquitted; the rest received sentences ranging from three to 12 years.

In the immediate postwar years, capturing Nazi war criminals was a top priority for the Allies. But priorities shifted. The Soviets came to be seen as a greater threat than ex-Nazis — a view welcomed by large segments of the West German public, who vocally demanded an end to war crimes trials and the release of prisoners.

On Jan. 31, 1951, John J. McCloy, the U.S. High Commissioner for Germany, reduced the sentences of 79 inmates at Landsberg, many to time already served. Among them was Alfried Krupp, released four days later. McCloy also restored Krupp’s industrial holdings.

Across West Germany, government officials, judges, professors and captains of industry who had dutifully served the Third Reich returned to prominence — with tacit U.S. approval. It’s a theme I explore in my book Nazis At The Watercooler: War Criminals In Postwar German Government Agencies.

Krupp was among them.

After his release, he resumed control of his empire — steelworks, coal mines, munitions plants — his rehabilitation aided by silence and selective memory. He died of bronchial cancer on July 30, 1967, at age 59. His funeral drew about 500 guests, including prominent figures from West German business, politics and labor.

The 1963 Newsweek portrait of Krupp was taken by Jewish photographer Arnold Newman, who was initially reluctant.

“When the editors asked me to photograph him, I refused,” Newman told American Photo. “I said, ‘I think of him as the devil.’ They said, ‘Fine — that’s what we think.’ So I was stuck with the job.”

In the photo, taken at one of Krupp’s factories, he appears almost diabolical — leering at the camera with a calculating gaze, his chin resting on folded hands in a pose that suggests both command and contempt. The industrial backdrop — steel beams, harsh lighting and stark shadows — frames him like a villain in a modern morality play.

Trump hasn’t publicly commented on the new Time photo. But he complained bitterly about one that appeared just two weeks earlier: “They ‘disappeared’ my hair, and then had something floating on top of my head that looked like a floating crown, but an extremely small one. Really weird!” he remarked.

The new cover, titled “Trump’s World,” seems more flattering. It shows him as the undisputed center of gravity — arms folded, gaze locked, seated in the Oval Office like a man who owns the room. Unlike Krupp, whose portrait radiated menace, Trump’s image is more ambiguous: part statesman, part strongman, part brand.