Send Arab Soldiers Into Iraq

The Iraq morass looks bleaker every day, with American casualty numbers rising and the expenses associated with military deployments raising questions of affordability. Yet in testimony to Congress last month, the commander of American forces in the region, General Tommy Franks, maintained that American troop levels — now numbering about 148,000 — would not drop until next year. He also suggested that American forces may be needed for another four years in order to establish a democratic and peaceful Iraq.

It is now obvious that re-making Iraq is far trickier than many had imagined. The difficulties weighing on the task of nation-building are indeed formidable.

First, Iraq is an extremely diverse country with a long history of internal violence. There are serious animosities between various clans, tribes and families: between Sunni and Shi’ite Muslims; between Kurds and Arabs; between Ba’ath party members and outsiders, and between the favored folks from Saddam’s hometown of Tikrit and others. This history portends that violence against the new occupiers is unlikely to dissipate quickly.

Secondly, absent proof of Saddam Hussein’s death — the recent killings of his sons Uday and Qusay notwithstanding — fears of his possible return greatly reduce our ability to gain cooperation on the ground.

Finally, even the most benign occupations are resented. In the Middle East this angst, supported by religious fervor, readily engenders violence against foreign troops. And we are at a particular disadvantage because our respect for religion, human rights and individual freedoms both enables and encourages extreme elements to take violent actions against us. Witness the moral hand-wringing Israelis have gone through as they take on Palestinian terrorism.

In this regard, imperial Japan or the Soviet Union, with their willingness to employ the harshest measures, were far better suited to be occupiers. Even so, the Soviet Union foundered in its Afghanistan quagmire. In Iraq, a sizable British and American troop presence — the former the old imperialists, the latter perceived as the new ones — is likely to fare no better than the Soviets in Afghanistan.

During the next four years that Franks expects our troops to maintain a presence in Iraq, American soldiers will in effect be deployed in order to “protect” the new government from dissident elements among its people. Already, the new Iraqi leadership’s domestic credibility has been damaged by perceptions that it is an American puppet-government.

The danger in staying in Iraq is ominous. The danger in leaving is no less forbidding. If our military is forced into an early exit because the American public begins to view our continuing losses as unacceptable, not only will the new Iraqi government fall, but the American reputation for toughness and staying power will be irreversibly damaged everywhere.

There is a way out of the Catch-22, however: Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states and other Arab countries, most of which expressed reservations about the war due to their concern for the Iraqi people, should be asked — and pressured, if need be — to send peacekeeping forces.

Doing so will allow us to greatly reduce American troop strength, thereby sparing American lives, freeing our forces for other contingencies and substantially minimizing our budgetary outlays.

These allied forces speak Arabic, thus greatly facilitating the daily, practical interfaces between foreign troops and the local population. And a military force comprised of Arabs and Muslims will likely blunt the Crusader image which arouses so much Middle East angst. Not least, such a contingent would offer visible proof of neighboring Arab states’ support for the new Iraqi government, lending the country’s new leaders enhanced regional credibility.

Can it be done? It’s possible, if we are willing to apply the economic and diplomatic muscle that we possess.

We can publicly state that this is an opportunity for those Arab states that opposed the war out of concern for the Iraqi people to take positive steps to enhance their welfare. We can lean on the Saudis, who are desperately trying to court favorable American government and public opinion. So, too, can we lean on the Egyptians, who receive a great deal of financial aid from us and yearn for a greater Middle East leadership role.

The smaller states, such as Jordan, Kuwait and Qatar, would most certainly agree. While their troop numbers would not be large, their willingness would place pressure on the others. Finally, our promise to publicly laud and acclaim such innovative actions by the responsible states of the region would enhance leadership and regime prestige in each of the participating countries.

A serious and concerted carrot-stick diplomatic approach is likely to evoke Arab cooperation with our challenges in Iraq — and if not, we’ll quickly find out who are real friends are.

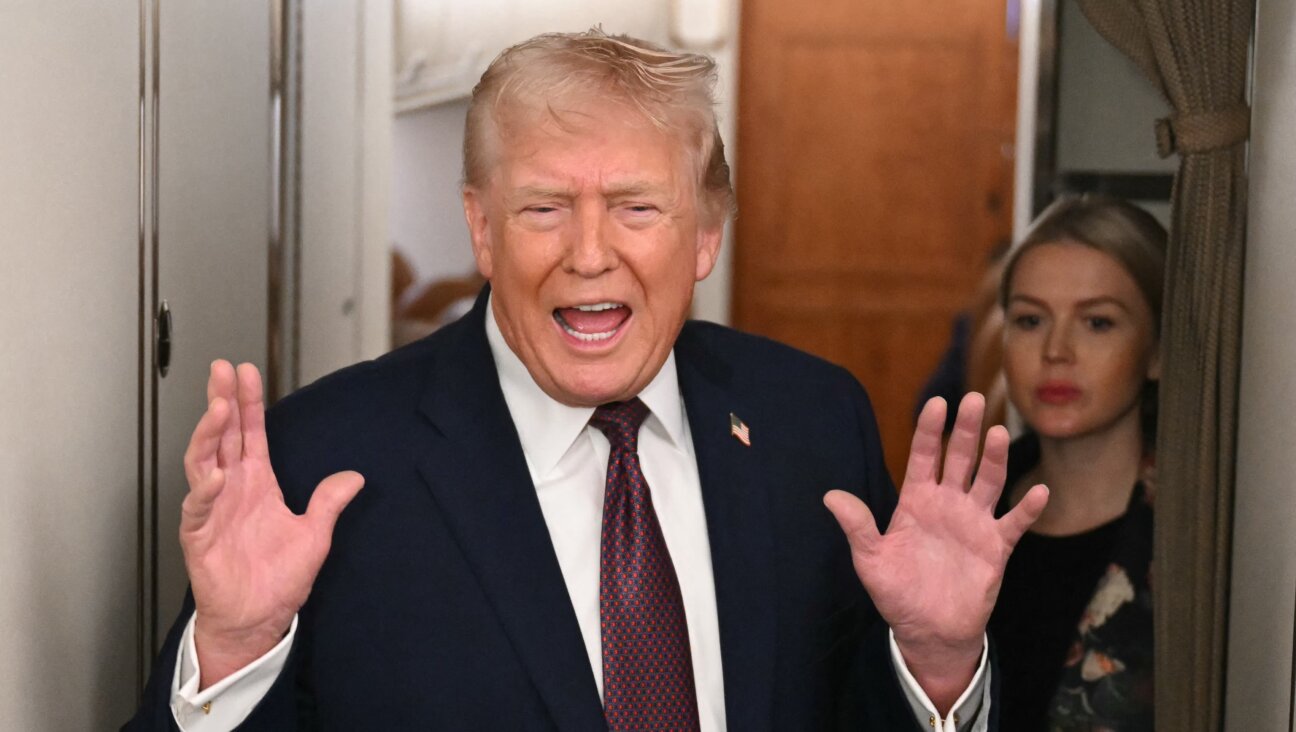

Donald Losman, a professor of economics at the National Defense University in Washington, is the author of “The Promise of American Industry” (Quorum Books, 1990).