What The Humble Olive Tree Teaches Us About Israel’s Past And Future

Image by Getty Images

In springtime, when the flowers of olive trees open in Jerusalem, pollen catches the Mediterranean winds and sails east. The pollen travels over the walls of the Old City, across the Kidron Valley to the Mount of Olives. It flies over walls, villages and settlements, then down from the hills and across the caves at Qumran. The pollen grains are now 400 meters below sea level, at the Dead Sea. Here, they either blow across the Sea to Jordan or sink into the saline waters. Each year, more pollen and dust arrives, sprinkling the sea’s bottom with a historical record of the springtime bloom. Over thousands of years, the sea’s sediment and its trapped pollen built into layers meters thick. This is the memory of the land, trapped in sediment. In this memory, we also glimpse the future.

The Dead Sea is now falling, drawn down by modest rainfall, upstream withdrawals for irrigation and evaporation ponds to harvest salt. As the water level drops, seabed deposits are exposed. By drilling cores into these salty gullies, then paring away layers of sediment, geologists and biologists reconstruct the past. Sediment and pollen deposits reveal the primacy of rainfall in the region. Changes in moisture have caused the Dead Sea, and its ice age predecessor, Lake Lisan, to rise and fall by hundreds of meters in elevation over the last quarter of a million years. Some centuries have been soaked, others parched. Pollen records follow the rain: from lush to desert, then back again.

Forces on the other side of the world drive these cycles. When icy meltwater pulsed into the Atlantic at the end of the last ice age, the colder ocean drove less heat and moisture into the Mediterranean. The rains stopped, the Dead Sea fell, and the land turned to desert. When the flow of ice water in the Atlantic was slow, the Levant rains returned. In these moist times, people moved and thrived. The first hominin and humans to leave Africa traveled into and through the region and adjacent Arabia, mostly during these wet intervals.

In more recent times, pollen records of domesticated crops, especially records of olives, show the waxing and waning of human culture in the region. In Dead Sea sediments from 6,500 years ago, olive pollen suddenly becomes more abundant, coincident with the species’ domestication. In the early Bronze Age, about 4,000 years ago, the climate was humid and olives thrived. There followed nearly 2,000 years of modest oscillations in climate and vegetation until the late Bronze Age, about 3,000 years ago. Sediments from 1250 to 1100 BCE contain almost no pollen from olive or other Mediterranean trees. Then the sediments themselves disappear. The geologists’ cores contain a blank space, the mark of an interruption to the orderly accumulation. The Dead Sea dropped so low that pollen landed on wind-blown dunes, not on water. When the rains returned, a century later, they fell on a land depopulated of humans and their domesticated trees. Archaeologists refer to the ensuing cultural upheaval as the “late Bronze Age collapse.”

Yet we are not passive victims of the vicissitudes of rainfall. Olive pollen persisted through a dry period around 3,000 years ago, evincing the work of a poorly known culture of successful arid-land orchardists. Likewise, the desires and skills of the Greeks, Romans and Byzantines turned the thin eastward drift of pollen from the Judean highlands into fat clouds.

Conversely, other periods had a good climate but little olive pollen. Pollen levels dropped sporadically during the lusher parts of the Bronze Age, when war and political instability prevented people from working with their trees. Then, during the late Iron Age, about 750–550 BCE, olive agriculture in the thriving kingdoms of Judah and Israel was undone by Assyrian and Babylonian invasions. If the social context is riven, farmers cannot care for trees and gain food from the land.

In the 1950s, Israeli inventors renegotiated the relationship among people, land and water. When the rain comes for only a few winter months, what is seen elsewhere in the world as waste becomes a precious liquid. Thin water pipes outfitted with hundreds of tiny, pressure-regulating openings enabled water to be applied to the land without waste. “Necessity is a good teacher” is an old European aphorism that I heard repeated many times in my conversations with Israeli farmers and olive researchers.

Greenland is now once again melting. This will not help the agricultural future of the Levant. When the World Resources Institute ranked countries by projected levels of “water stress” in the coming decades, Israel was listed in the highest tier. The Dead Sea is close to the point at which olive pollen will again fall on dust, not on water.

In response, researchers have developed new varieties of olives, grown in hedgelike rows with efficient drip irrigation. The yields from these plantations are prodigious, even in years of little rainfall. The Israeli horticulturist who pioneered this method, Shimon Lavee, was laughed at when he first presented his innovative methods to international conferences. Now, decades later, his approaches have spread as far as Spain and Australia.

The latest climate predictions suggest that severe and widespread droughts will only become more common. The technologies born in Israel’s fields are needed around the globe. Pollen from Jerusalem reaches only as far as the Dead Sea. But the ideas born under Israel’s olive branches reach further, across a thirsty world.

David George Haskell explores the many ways that the lives of people and trees are connected in his new book, “The Songs Of Trees: Stories From Nature’s Great Connectors” (Viking). His previous book, “The Forest Unseen,” was a finalist for the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction and won numerous awards, including the 2013 National Academies Best Book Award. He is a professor of biology and environmental studies at the University of the South, in Sewanee, Tennessee.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 3

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

- 4

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion Yes, the attack on Gov. Shapiro was antisemitic. Here’s what the left should learn from it

-

News ‘Whose seat is now empty’: Remembering Hersh Goldberg-Polin at his family’s Passover retreat

-

Fast Forward Chicago man charged with hate crime for attack of two Jewish DePaul students

-

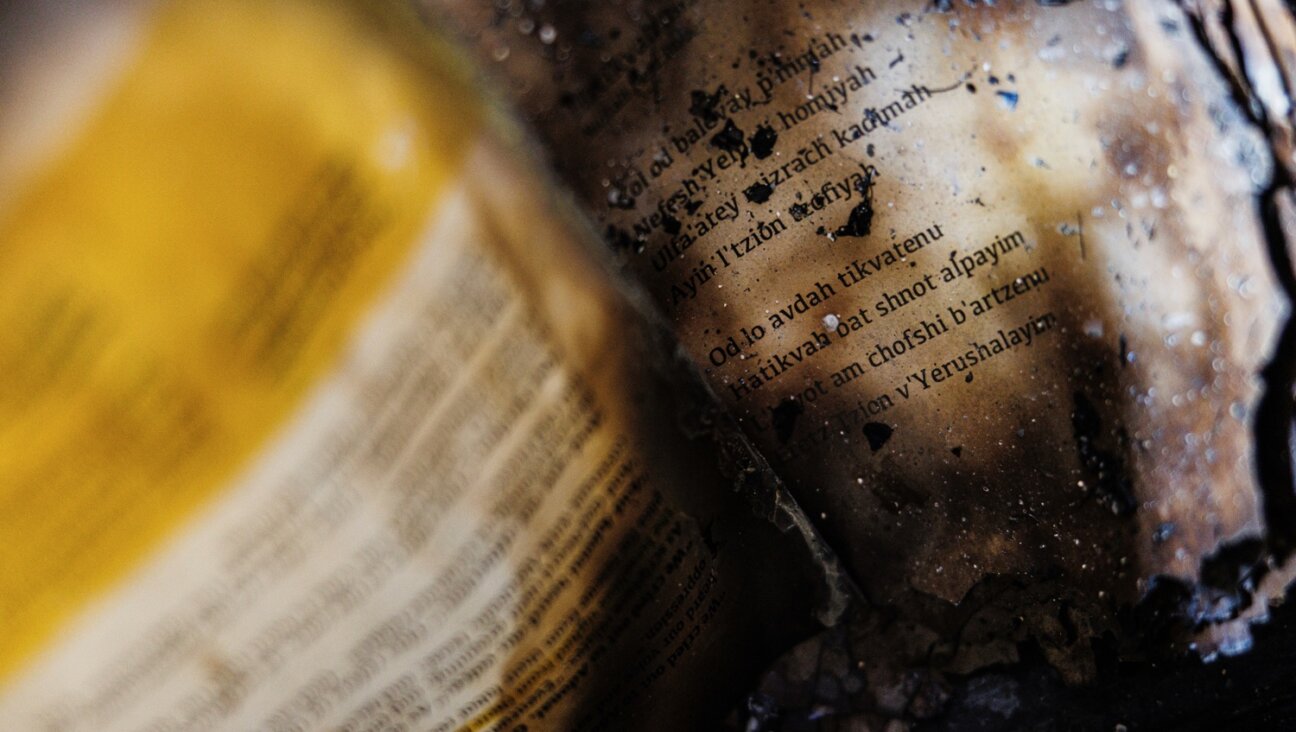

Fast Forward In the ashes of the governor’s mansion, clues to a mystery about Josh Shapiro’s Passover Seder

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.