Lost and Found in Brooklyn

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Earlier this week, Lucette Lagnado wrote about an arrogant revolution and about mourning her Arab Spring. Her posts are being featured this week on The Arty Semite, courtesy of the Jewish Book Council and My Jewish Learning’s Author Blog Series. For more information on the series, please visit:

This past weekend I was lost — and found — in Brooklyn.

My Sunday began with an appearance on a panel about the Arab Spring at the chic, hipsterish Brooklyn Book Festival. It was an animated discussion, and my fellow panel-members were amiable, but I felt lonely, very much in the minority as I spoke out against the brutal attack on the Israeli Embassy in Cairo. The attempted storming of the embassy last week was a turning point as far as I was concerned, a time to start asking tough questions about the revolution and whether it had gone seriously off-track, to demand to know what happened to the early goals of democracy and peace on Tahrir Square.

The consensus, though, was that revolutions took time to play out — one member suggested 100 years.

And I thought there was such a desperate need for change — immediate reforms. One thoughtful panel member from Cairo did suggest that many Egyptians were shocked by the attack, that it was unexpected; I was heartened to hear at least that there was a sense of shame about it in Egypt.

I walked out feeling oddly blue, melancholy. Here I was in Brooklyn, where I grew up, and yet I was struck by that feeling of not belonging that returns to haunt me every once in a while.

As I wandered the streets of Brooklyn Heights with its multi-million dollar mansions and elegant residents, and then of nearby Park Slope which is, if possible, looking even sleeker these days, I realized that this fashionable Brooklyn had nothing to do with the Brooklyn of my childhood, the borough where my family and I had once sought refuge, where we had found a haven among equally impoverished refugees from the Levant.

I also knew the only possible way to cope with my funk was to go immediately to that Brooklyn.

I have always thought it was odd that with this Brooklyn renaissance, the fact that some of the borough’s most God forsaken areas have become de rigueur, my little enclave of Bensonhurst has remained decidedly un-chic.

I return every few months and find it to be pretty much the same as it was in my childhood — staid and lacking in the coolness factor.

Some more immigrant groups have moved in, to be sure, I see a lot of Russians, and even some Hasidim — but not a single hipster. Not one.

Nor any of the young professional families that favor organic food co-ops.

No, those quiet somewhat dreary blocks are pretty much the way they were when I was a kid, longing to escape and wishing there was more excitement.

My trips to Bensonhurst always have a ritual quality to them, like a religious pilgrimage. I must go to this block, I tell myself, I must pay my respects to that building.

There are no people left there that I knew, not a single familiar face — my community long moved out — yet I keep returning.

The ritual includes taking my (very obliging) husband to key markers of my childhood and pointing them out all over again.

“This was our first apartment in America,” I’ll say, “This was where Key Food, my first American supermarket was situated.”

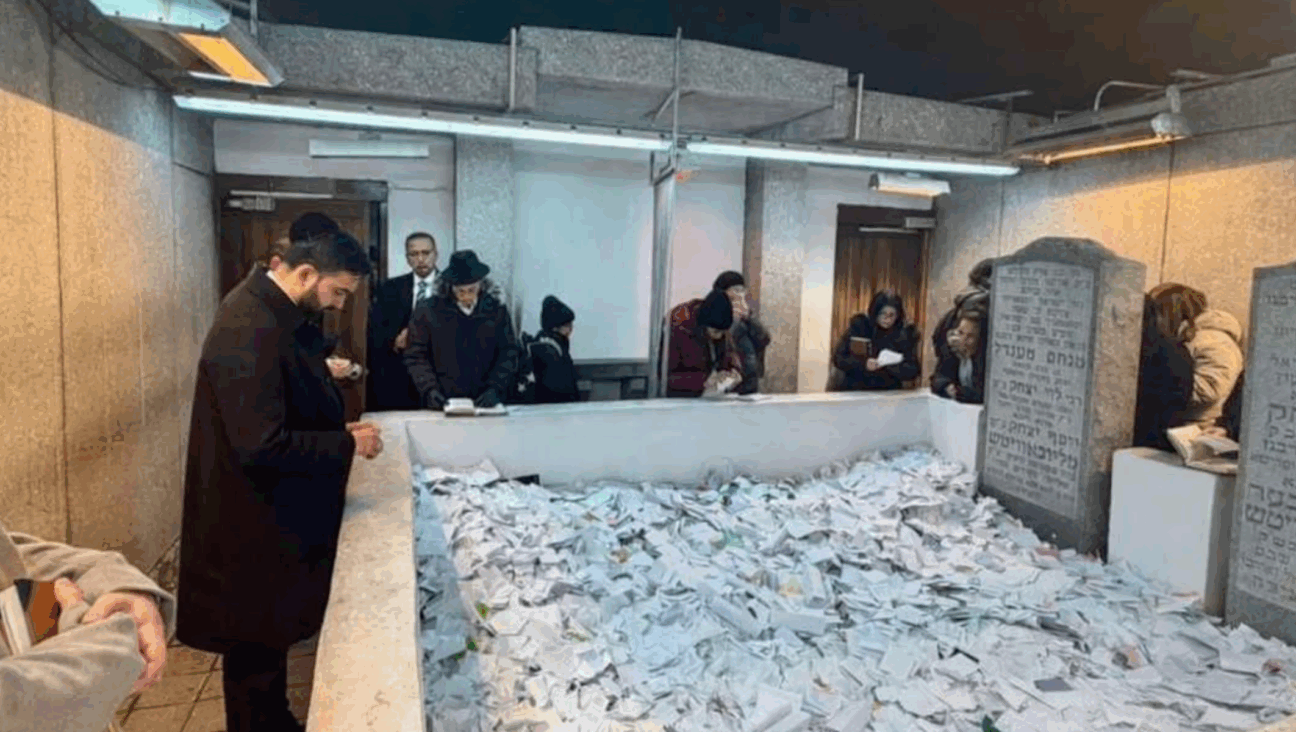

The high point of all such trips is a visit to 67th street, the block of the Magen David Synagogue (“The Shield of David” in my book), once the center of Syrian Jewish life in New York, and its frail little neighbor, the building that housed my shul.

Magen David is still there, but it is a mortuary now. I have been told there are occasional services, possibly even for the high holidays, but its central function is clear, and has been clear for years — it is where the community comes to honor its dead.

No matter how many times I hear that, it still shocks me, still makes me sad.

As for the little annex, the one that I refer to as the Shield of Young David in my memoir, it has gone through a thousand incarnations since it was sold in the 1970s. These days, it appears to be a religious school.

On this Sunday afternoon, I make a discovery that actually helps me combat my Brooklyn Heights blues. There in the front of the building of my old shul are children — young Orthodox children scampering about, running around the courtyard.

“They are playing in the courtyard, the way you did as a child,” my husband points out.

It has taken years, decades, yet I realize that against the odds, hope has come back to this small corner of Brooklyn that continues to haunt my imagination as nowhere else on earth.

-

- **Lucette Lagnado’s most recent book,

“The Arrogant Years: One Girl’s Search for Her Lost Youth, from Cairo to Brooklyn,” is now available. Lucette won the 2008 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature for her memoir “The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit: A Jewish Family’s Exodus from Old Cairo to the New World.” *

The Jewish Book Council is a not-for-profit organization devoted to the reading, writing and publishing of Jewish literature. For more Jewish literary blog posts, reviews of Jewish books, book club resources, and to learn about awards and conferences, please visit www.jewishbookcouncil.org.

MyJewishLearning.com is the leading transdenominational website of Jewish information and education. Visit My Jewish Learning for thousands of articles on Judaism, Jewish holidays, Jewish history, and more.