What sort of Yiddish did Jews in Hungary speak?

Hungarian Yiddish may be today’s most common Yiddish dialect but many Hungarian Jews in the old country didn’t even speak Yiddish.

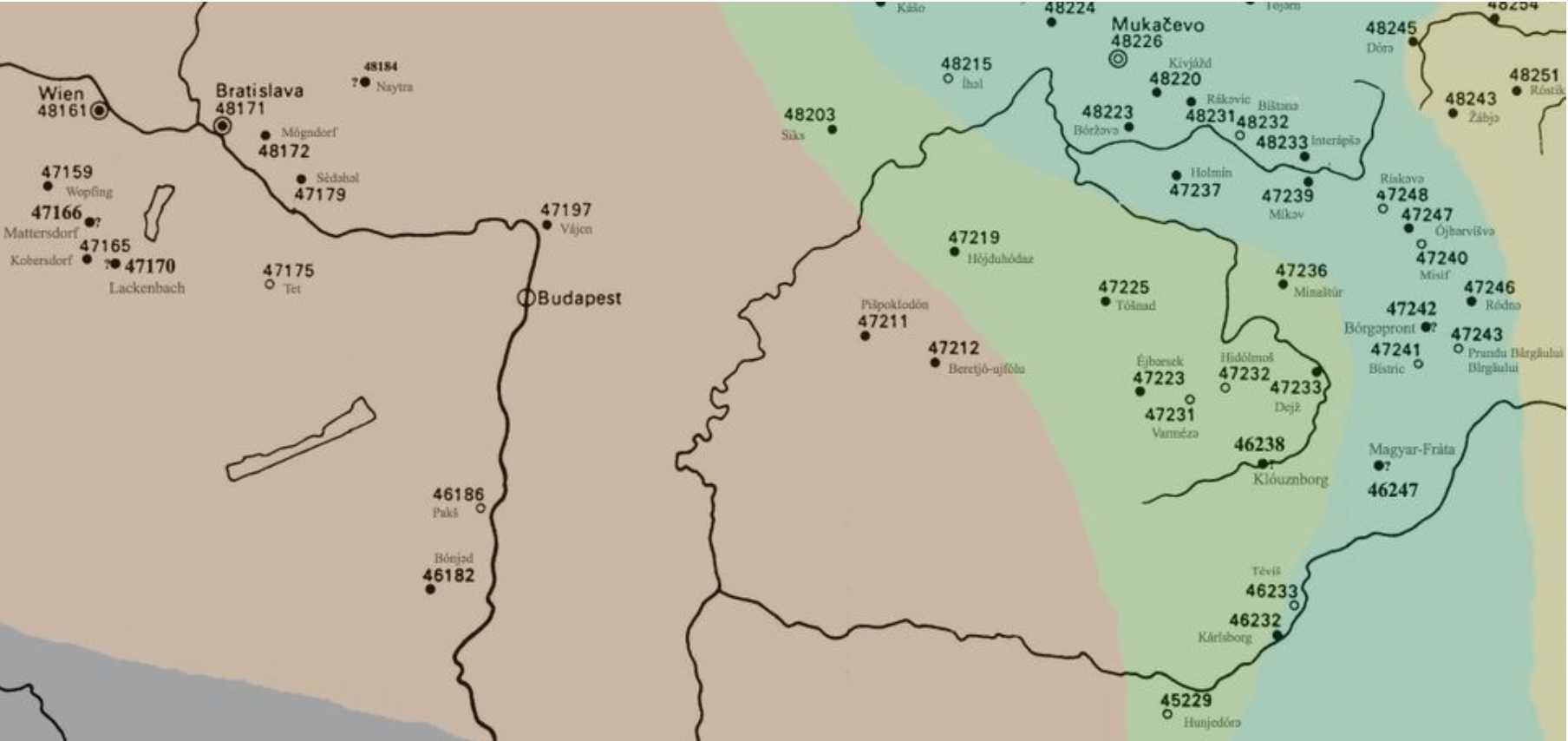

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

This article originally appeared in Yiddish here.

When you hear Yiddish on the streets of Brooklyn these days, the likelihood is it’s Hungarian Yiddish. Even Galician, Polish, and Lithuanian Hasidim use the Hungarian dialect today. One reason could be that the Hungarian-descended Satmar Hasidim have been more successful at maintaining Yiddish as its daily vernacular. Most Hungarian-Hasidic women, for example, speak Yiddish among themselves, while women from other Hasidic groups tend to speak English.

But calling these Hasidim “Hungarian” doesn’t mean that they immigrated from present-day Hungary, a relatively small country (although it’s four times the size of Israel). The “Jewish” geography of Hungary is the once vast Hungarian kingdom that existed before World War I, which included large expanses of today’s Romania, Slovakia, Ukraine, Croatia and Austria. In this respect, when speaking of the pre-World War I Jewish community in Hungary, you can compare it with “Jewish Lithuania”, which is exponentially larger than the contemporary State of Lithuania, and also includes Belarus, large parts of Russia, Ukraine, Latvia, and Poland. “Jewish Lithuania” covers mostly the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the Middle Ages, one of the largest nations in European history.

When the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed and new nations emerged from former Hungarian territories, many ethnic Hungarians remained on the other side of the new borders, while Jews in the territory of modern Romania, Ukraine, and Slovakia continued living in a culturally Hungarian environment, which includes the historical centers of “Hungarian” Hasidism: Satmar and Klausenburg are both cities in present-day Romania (Satu Mare and Cluj-Napoca, respectively); Munkacs (Mukachevko) is in Ukraine; and Nyitra (Nitra) is in Slovakia.

There is a historical irony in the fact that Hungarian Hasidim speak more Yiddish today than other groups: in the old country, Hungarian Jews more often spoke Hungarian than Yiddish, and in western Hungary some even spoke German, or a mix of German and Yiddish. Among the generation of Hungarian-Jewish immigrants that arrived in the United States after World War II, and helped established the current Hasidic dynasties, many spoke Yiddish with a strong Hungarian accent. On the streets of Williamsburg many Jews of the older generation continued to speak Hungarian.

So what kind of Yiddish did the Hungarian Jews speak in the old country? Samples of this can be heard in a handful of old recordings, as in the interviews conducted by the Language and Culture Atlas of Ashkenazic Jewry at Columbia University. Linguist Uriel Weinreich, who devised the Atlas project, and his assistants, interviewed many native-informant speakers of Hungarian Yiddish in the 1960s. He was particularly interested in Hungarian Yiddish because until that time linguists had spent very little time studying it since the Yiddish language, culture, and literature played a smaller role in Hungary than in Galicia, Poland and Russia.

Thanks to Weinreich’s interviews we can reconstruct a relatively precise picture of Hungarian Yiddish before the War. The old Hungarian territories were separated into two primary Jewish cultural settlements: “Upper Hungary” (Oberland) in the west and the “Underland” (Unterland) in the east. The two regions were sharply divided in terms of language, culture, and religion. The “Underlanders” for the most part only spoke Yiddish and were mostly Hasidim. The Orthodox Jewish Oberlanders were, for the most part, anti-Hasidic — they were known as “Ashkenazim” — and they spoke a different dialect, a kind of Western-Yiddish that is now extinct. The vast majority of Hungarian Jews were Reform or completely assimilated, who spoke Hungarian or German.

Nonetheless, there is no set border between Upper Hungary and the Underland. Hasidim and “Ashkenazim” lived in the same shtetls, and in a larger settlement people spoke a mixed dialect, neither upper nor lower. Weinreich came to the conclusion that in previous times the “Underlanders” had spoken Western Yiddish like the Oberlanders, but that dialect was diluted by the large masses of Galician Jews who migrated from the north during the nineteenth century.

For many places in Upper Hungary, Weinreich was unable to find any Yiddish language-informants because the language in those places was already extinct. From the Slovakian capital Bratislava (Pressburg), home to a famous yeshiva founded by the Chasam Sofer, Weinreich had to make do with one Jew who could recall only select Yiddish words and sayings in Yiddish from earlier generations. Before World War II the Bratislavan Jews were already speaking mostly German. This was also the case in the Burgenland, which belongs to Austria today: the language informants could dimly recall how their grandparents spoke, but they themselves spoke only German.

Weinreich found a group of reliable native informants from smaller shtetls in the Oberland, where Yiddish was still spoken. Nonetheless, the influence of German and Hungarian on their speech was recognizable: for certain terms they had already forgotten the Yiddish words and used a German or Hungarian word instead. It turns out that the Oberland dialect had already begun to disappear even before the war began. In their dialect, you could hear a simplification of the grammatical system, so that instead of the different definite articles signifying masculine, feminine, or neutral grammatical genders (“der,” “di,” and “dos,” respectively), these speakers usually only said “de,” similar to contemporary Hasidic Yiddish. It’s possible that this particular detail of contemporary Hasidic Yiddish derived from the Oberlanders, who in part became Hasidim only after they came to the United States. But this isn’t certain, because the Oberlanders didn’t have a significant influence on the development of Hasidic Yiddish.

Even among the Underland native-informants, certain speakers were more fluent in Hungarian than Yiddish, and their grammar was uncertain. Such uncertainty was probably very widespread among Hasidim, whose first language was Hungarian, and perhaps this alone explains the contemporary universality of the article “de.” There might be several reasons for this phenomenon, and no doubt the fact that English only uses one article — the gender-neutral article “the” — plays a role as well.

Although the Hungarian Hasidim are the predominant Yiddish speakers in the world today, this hasn’t resulted in an influx of Hungarian words into the language. In fact, they use very few words from Hungarian, but do use many German words. This is probably because enough Hasidim from German-speaking areas, particularly from Galicia, migrated to Hungary with a Germanic vocabulary, but without any knowledge of Hungarian.

What’s clear is that Hasidic Yiddish developed from various European dialects, not only from Hungarian Yiddish. You could say it’s a child with many fathers!