This synagogue ‘gets’ why you need Yiddish on Yom Hashoah

Of the six million Jews who were killed in the Holocaust, 85% were Yiddish speakers.

(From left): Hebrew Institute Rabbi Steven Exler; Holocaust survivors Leo Scheiner, his sister Doris Seaman and Evelyne Appel, and HIR founder Rabbi Avi Weiss Photo by ©️Robert Kalfus 2025

As a member of the Riverdale-Yonkers Jewish community, I’ve heard for years about the Yom Hashoah Seder conducted by the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale, also known as The Bayit. This year, as I debated which Yom Hashoah program to go to (there were several throughout the neighborhood), I decided on the Seder.

I’m glad I did. As someone who spends most of my time promoting Yiddish culture both personally and professionally, I was amazed, and deeply moved, to see how much Yiddish content was included in the program.

85% of the six million Jews who were killed in the Holocaust were Yiddish speakers. As a result, the Nazi genocide was not only physical, but spiritual, decimating the thousand-year old civilization of Eastern European Jewry.

And yet, gleaning from what fellow Yiddish supporters have told me over the years, few synagogues in New York or elsewhere include songs or readings in mame-loshn. Those who do often relegate it to one stanza of Hirsh Glik’s Yiddish “Partisan Hymn.”

Why is that? My guess is that many rabbis and lay leaders hesitate to include the language because most of the Yiddish-speaking survivors have passed on and almost no one in the audience understands it. But most American Jews don’t know Hebrew either, and this doesn’t stop congregations from including Hebrew songs and prayers in their Yom Hashoah programs.

The Hebrew Institute is a popular open Orthodox Jewish congregation founded by Rabbi Avi Weiss, affectionately called Rav Avi by his congregants — a well-known activist in defense of Israel and in expanding roles for women in Orthodox Judaism. After his retirement in 2015, Rabbi Steven Exler took over.

As soon as I arrived at the event that evening, I noticed something else that was different about this commemoration. Before entering, everyone was encouraged to clip a Jewish star onto their clothing. The message was clear: Just as Jews are told on Passover night to experience the Seder as if they themselves were slaves in Egypt, visitors were encouraged to empathize with the generation of their great-grandparents who had suffered under Nazi rule. By putting on the Jewish badge, audience members transitioned from spectators to participants.

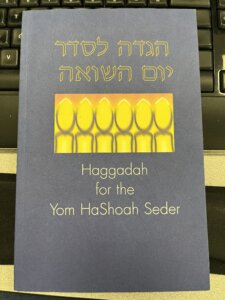

But for me, it was the including of Yiddish passages and songs into the Yom Hashoah Haggadah that brought the most authenticity to the Seder. When Rav Avi was compiling the Haggadah about 25 years ago (it was published in 2000), he knew from the beginning that it would be trilingual: English, Hebrew and Yiddish. “Yiddish was the language of the Shoah,” he wrote me in an email. “It was a concrete decision that in each section there had to be a Yiddish song.”

Years later, Yiddish narration was added, provided by an active member of the synagogue, the researcher and Yiddish activist Gella Schweid Fishman.

So last Thursday evening, as the shul’s rabbis instructed us to open our Haggadahs, the program began with several Yiddish pieces of narration read aloud by an older member of the community, Isaac Geld:

Dos iz di gele late vos der roshe, yemakh shemoy, hot getsvungen undzere eltern tsu trogn in di lender fun eyrope in der tsayt fun dem groysn khurbn fun undzer folk yisroel.

(This is the yellow badge that the evil one, may his name be erased, forced our people to wear in the lands of Europe during the time of the great destruction of our people Israel.)

This was followed by more Yiddish passages, each of which was translated for the audience by the HIR president Jessica Loeser.

Even more surprising was when the microphone was handed over to Rav Avi himself, sitting quietly in the audience. In a smooth, melodic voice he sang the powerful Yiddish song “Undzer shtetl brent!” (Our Town is Burning) where author Mordechai Gebirtig cries out: “Dear brothers, our shtetl is burning! Yet you stand there staring with your arms folded as the flames grow higher — our shtetl is burning!”

Having a rabbi sing in Yiddish sends a message to congregants that including the language on Yom Hashoah matters.

Other Yiddish highlights of the evening: Hearing a recording of the song “Ikh benk aheym” (“I Long for Home”) written in the Vilna Ghetto; Rav Avi Weiss singing another song — the iconic “Afn Pripetshik” (“On the Hearth”) about a rebbe teaching children the Hebrew alphabet; and the audience standing to sing the Yiddish Partisan Hymn.

Of course, most synagogues don’t have a rabbi who can sing in Yiddish or congregants who can recite the Yiddish narration. But with all the possibilities that Zoom affords today, there’s no reason they can’t ask a klezmer or Hasidic singer to join them or to send a video of themselves singing Yiddish songs while the audience sees the lyrics in the page in front of them.

By including the language of prewar Eastern European Jewry in a Yom Hashoah ceremony, we are not only commemorating how they died, but also expressing appreciation for their amazing contribution to our lasting Jewish heritage.

_________